Slumping landslide in Mars’ glacier country

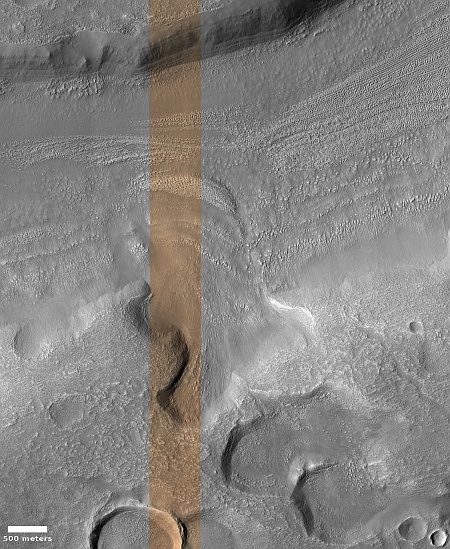

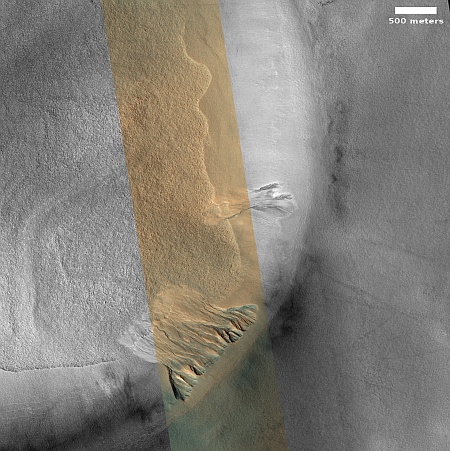

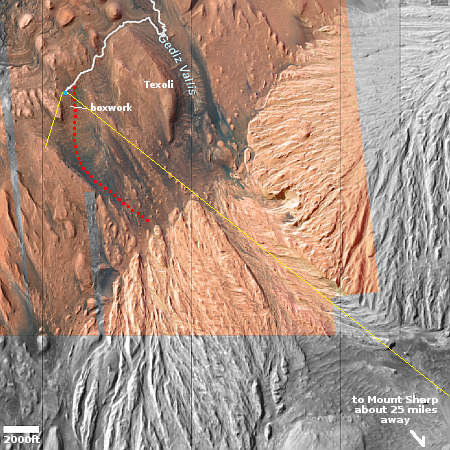

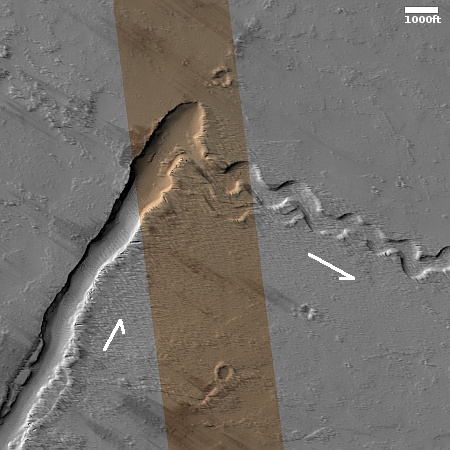

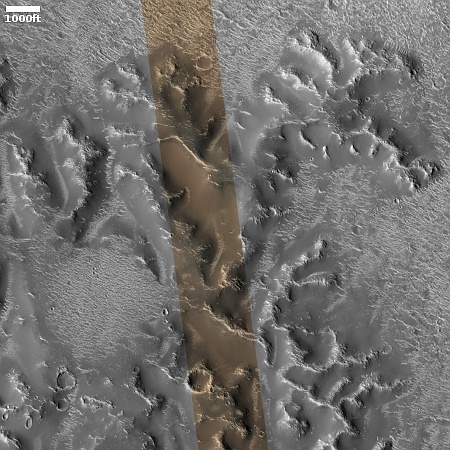

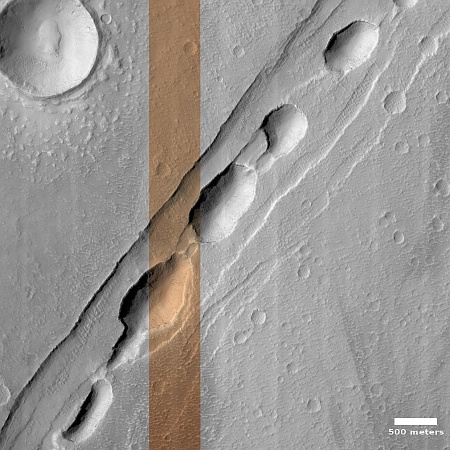

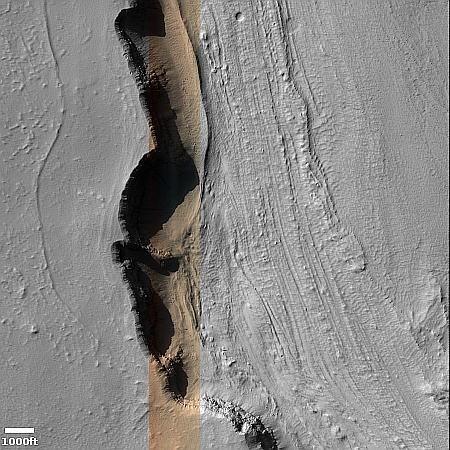

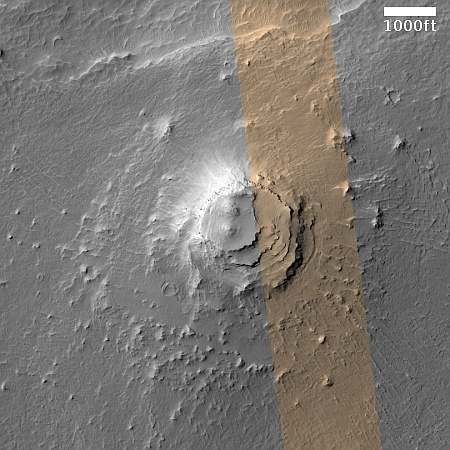

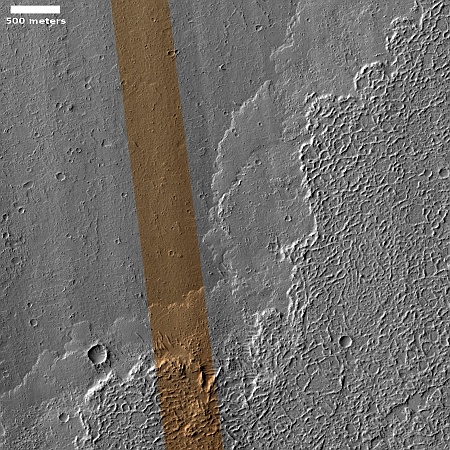

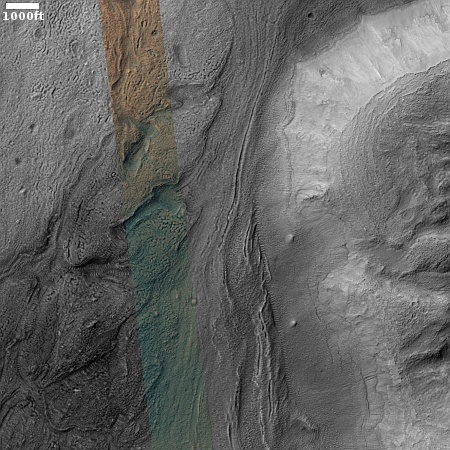

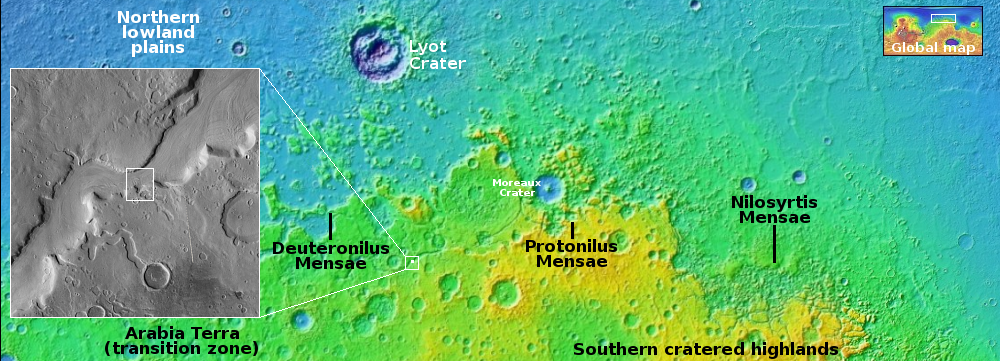

Cool image time! The picture to the right, rotated, cropped, reduced, and sharpened to post here, was downloaded on July 1, 2025 from the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO).

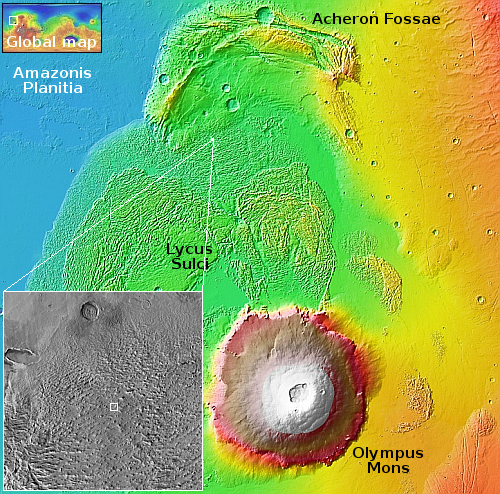

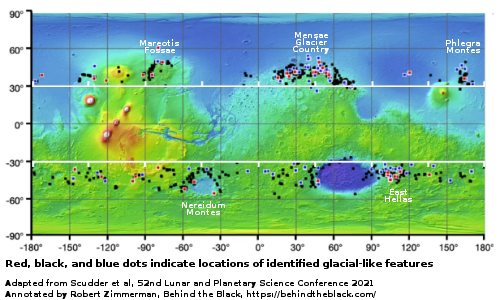

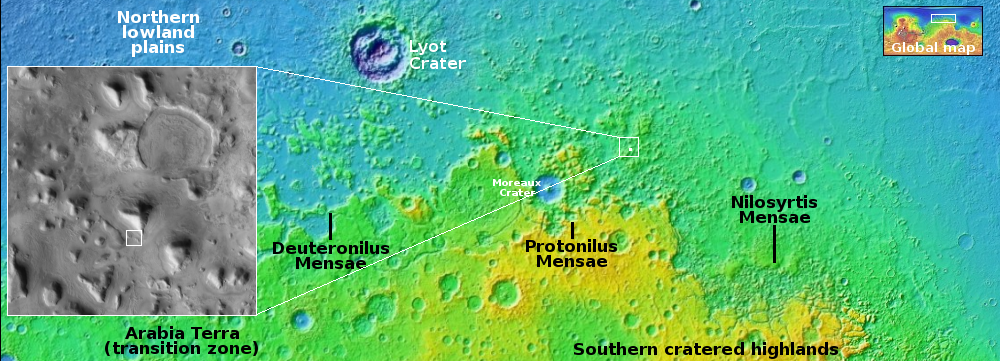

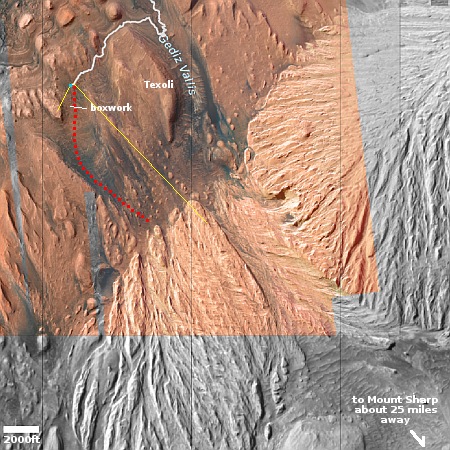

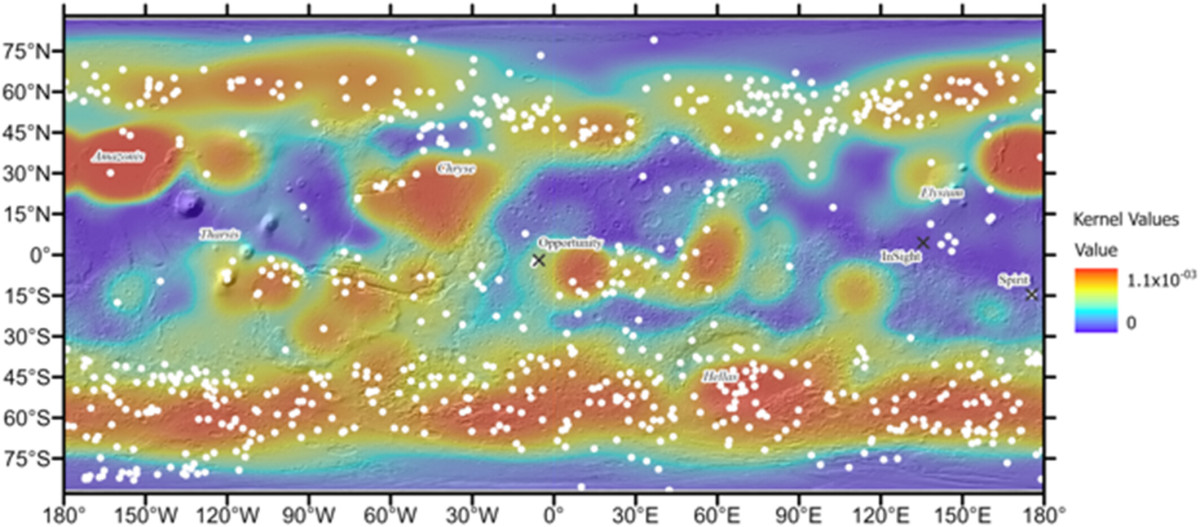

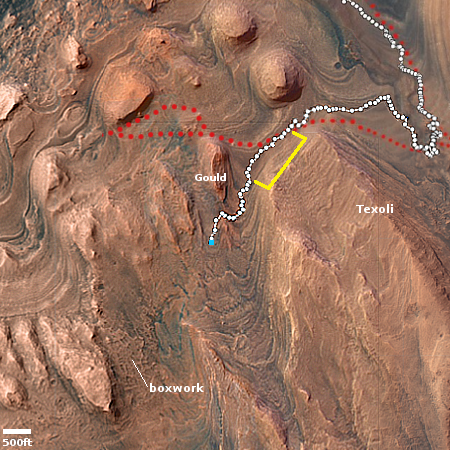

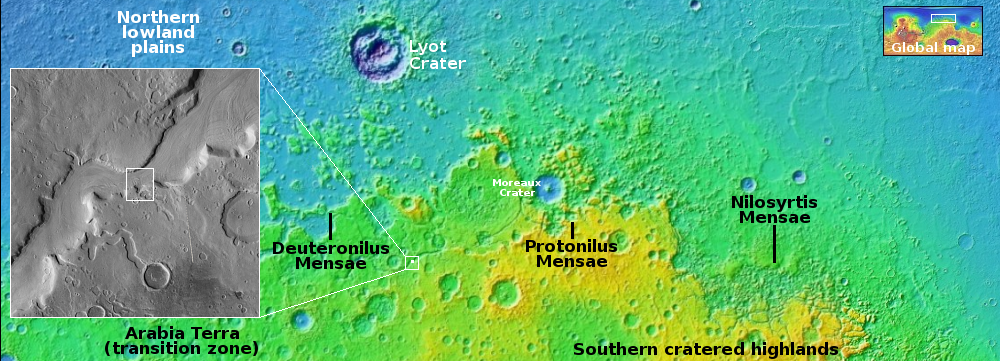

Labeled by the science team as a “flow,” it shows what appears to be a major collapse of the canyon’s south wall. The white dot on the overview map above marks the location, near the center of the 2,000-mile-long strip in the northern mid-latitudes of Mars that I label “glacier country” because almost every single high resolution image of this region shows glacial features.

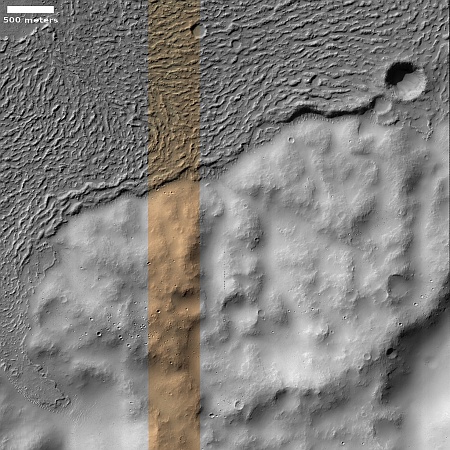

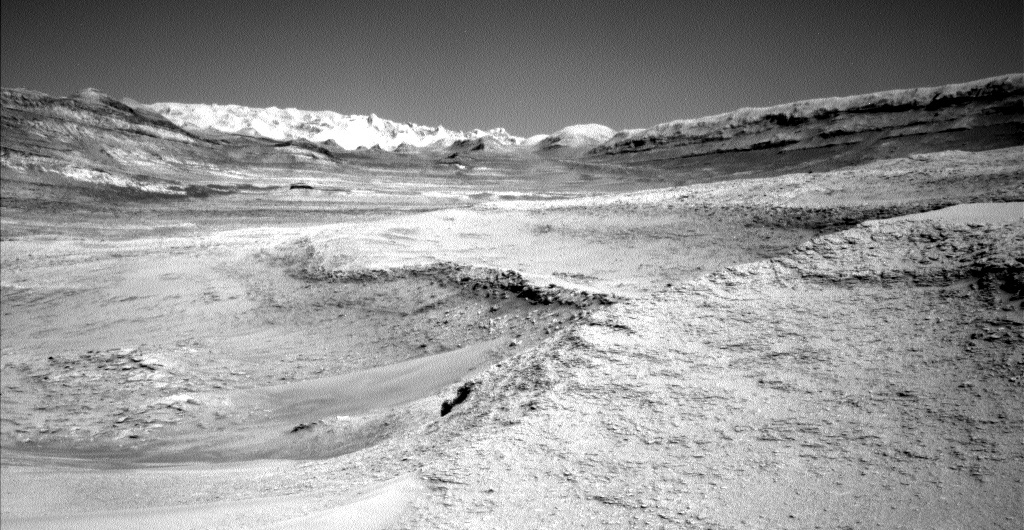

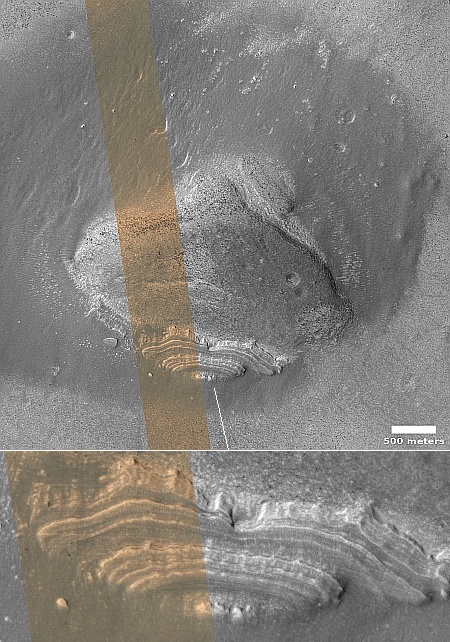

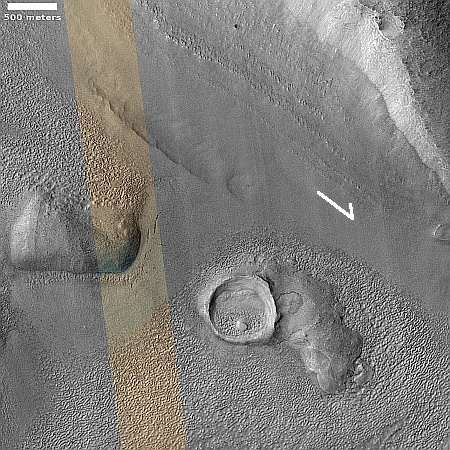

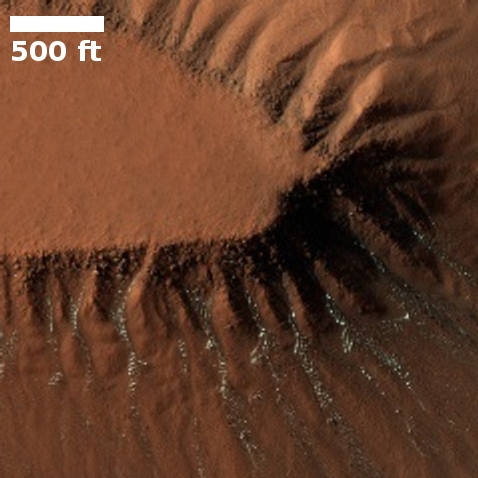

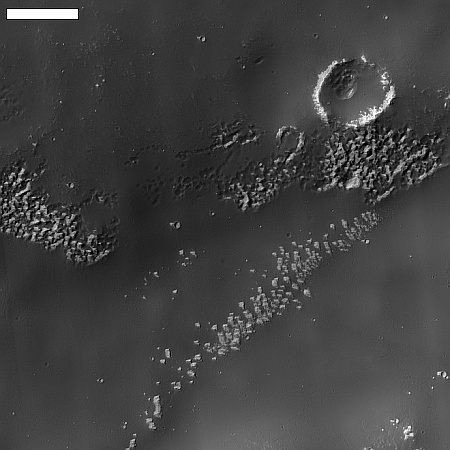

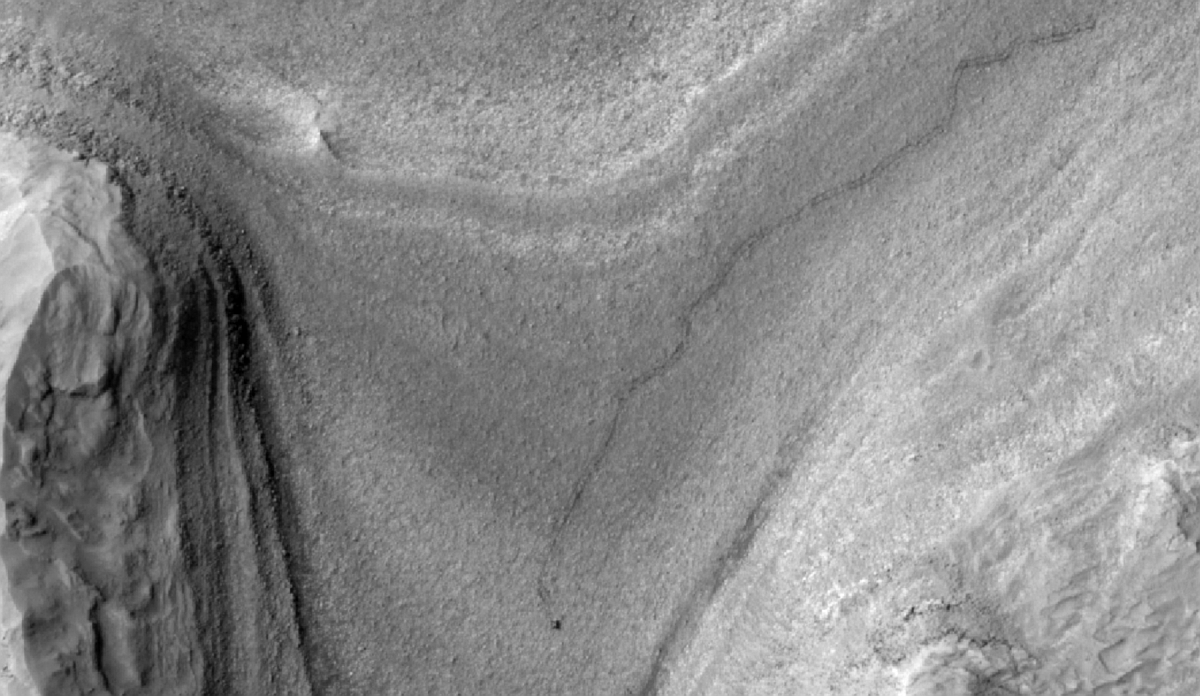

This picture is no exception. First, the canyon appears filled with a glacial material, though its flow direction is unclear. Orbital elevation data suggests that this collapse is actually at the canyon’s high point, with the drainage going downhill to the east and west.

Second, the collapse itself doesn’t look like an avalanche of rocks and bedrock, but resembles more a mudslide. Since liquid water cannot exist in Mars’ thin atmosphere and cold climate, the soft nature of the slide suggests it is dirt and dust impregnated with ice. At some point, either because of the impacts that created the craters on its southern edge or because the sun warmed the ice causing it sublimate away thus weakening the ground structurally, the entire cliff wall slumped downward to the north.

The canyon itself is about 800 feet deep. It likely formed initially along a fault line, with ice acting over time to widen and extend it.

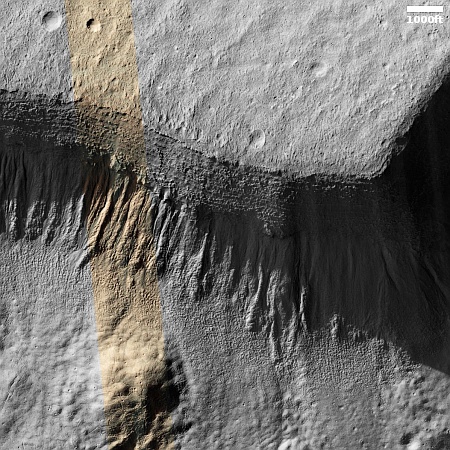

Cool image time! The picture to the right, rotated, cropped, reduced, and sharpened to post here, was downloaded on July 1, 2025 from the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO).

Labeled by the science team as a “flow,” it shows what appears to be a major collapse of the canyon’s south wall. The white dot on the overview map above marks the location, near the center of the 2,000-mile-long strip in the northern mid-latitudes of Mars that I label “glacier country” because almost every single high resolution image of this region shows glacial features.

This picture is no exception. First, the canyon appears filled with a glacial material, though its flow direction is unclear. Orbital elevation data suggests that this collapse is actually at the canyon’s high point, with the drainage going downhill to the east and west.

Second, the collapse itself doesn’t look like an avalanche of rocks and bedrock, but resembles more a mudslide. Since liquid water cannot exist in Mars’ thin atmosphere and cold climate, the soft nature of the slide suggests it is dirt and dust impregnated with ice. At some point, either because of the impacts that created the craters on its southern edge or because the sun warmed the ice causing it sublimate away thus weakening the ground structurally, the entire cliff wall slumped downward to the north.

The canyon itself is about 800 feet deep. It likely formed initially along a fault line, with ice acting over time to widen and extend it.