Ingenuity’s 55th flight completed

The Ingenuity engineering team today updated the helicopter’s flight log, showing that the 55th flight occurred on August 12, 2023, one day later than originally planned, and flew 881 feet for 143 seconds, 61 feet and 9 seconds longer than planned.

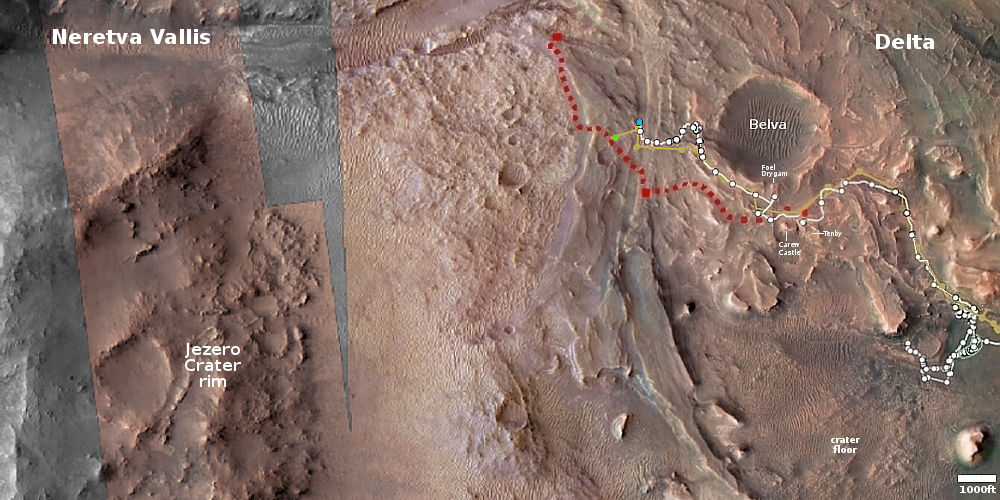

The overview map above shows the present locations of both Perseverance and Ingenuity. The green dot marks Ingenuity’s new position, while the blue dot marks where Perseverance presently sits in Jezero Crater. Based on this map, the main goal of the flight was apparently to fly Ingenuity over a route that Perseverance will likely use to return to its planned route, as indicated by the red dotted line.

The Ingenuity engineering team today updated the helicopter’s flight log, showing that the 55th flight occurred on August 12, 2023, one day later than originally planned, and flew 881 feet for 143 seconds, 61 feet and 9 seconds longer than planned.

The overview map above shows the present locations of both Perseverance and Ingenuity. The green dot marks Ingenuity’s new position, while the blue dot marks where Perseverance presently sits in Jezero Crater. Based on this map, the main goal of the flight was apparently to fly Ingenuity over a route that Perseverance will likely use to return to its planned route, as indicated by the red dotted line.