Physicists shrink their next big accelerator

Because of high costs and a refocus in research goals, physicists have reduced the size of their proposed next big particle accelerator, which they hope will be built in Japan.

On 7 November, the International Committee for Future Accelerators (ICFA), which oversees work on the ILC, endorsed halving the machine’s planned energy from 500 to 250 gigaelectronvolts (GeV), and shortening its proposed 33.5-kilometre-long tunnel by as much as 13 kilometres. The scaled-down version would have to forego some of its planned research such as studies of the ‘top’ flavour of quark, which is produced only at higher energies.

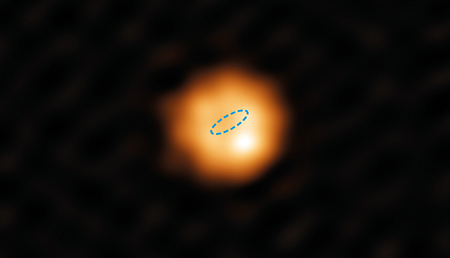

Instead, the collider would focus on studying the particle that endows all others with mass — the Higgs boson, which was detected in 2012 by the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN, Europe’s particle-physics lab near Geneva, Switzerland.

Part of the reason for these changes is that the Large Hadron Collider has not discovered any new particles, other than the Higgs Boson. The cost to discover any remaining theorized particles was judged as simply too high. Better to focus on studying the Higgs Boson itself.

Because of high costs and a refocus in research goals, physicists have reduced the size of their proposed next big particle accelerator, which they hope will be built in Japan.

On 7 November, the International Committee for Future Accelerators (ICFA), which oversees work on the ILC, endorsed halving the machine’s planned energy from 500 to 250 gigaelectronvolts (GeV), and shortening its proposed 33.5-kilometre-long tunnel by as much as 13 kilometres. The scaled-down version would have to forego some of its planned research such as studies of the ‘top’ flavour of quark, which is produced only at higher energies.

Instead, the collider would focus on studying the particle that endows all others with mass — the Higgs boson, which was detected in 2012 by the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN, Europe’s particle-physics lab near Geneva, Switzerland.

Part of the reason for these changes is that the Large Hadron Collider has not discovered any new particles, other than the Higgs Boson. The cost to discover any remaining theorized particles was judged as simply too high. Better to focus on studying the Higgs Boson itself.