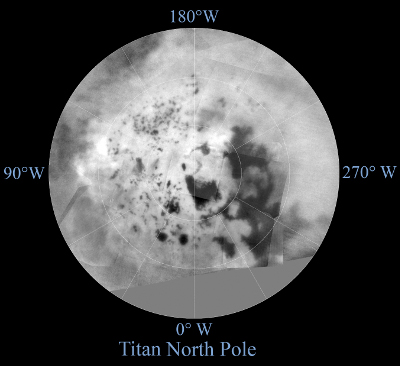

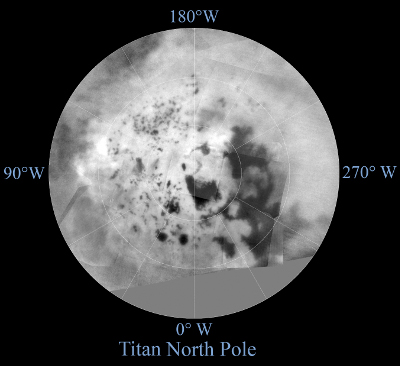

New global maps of Titan

The Cassini science team has released new maps of Titan, including new maps of both poles, assembled from images taken during the 100 flybys that the spacecraft has made of the moon since it arrived in orbit around Saturn.

The scale is rough, just less than a mile at best, and there is no topographic information because the thick atmosphere allows for no strong sunlight or shadows. The images show differences in surface brightness, which does tell us where Titan’s dark methane lakes are.

This is likely the best we will get of Titan for decades, until another spacecraft is sent there.

The Cassini science team has released new maps of Titan, including new maps of both poles, assembled from images taken during the 100 flybys that the spacecraft has made of the moon since it arrived in orbit around Saturn.

The scale is rough, just less than a mile at best, and there is no topographic information because the thick atmosphere allows for no strong sunlight or shadows. The images show differences in surface brightness, which does tell us where Titan’s dark methane lakes are.

This is likely the best we will get of Titan for decades, until another spacecraft is sent there.