The problem Starship poses to NASA and Congress

An interesting essay published earlier this week in The Space Review raises the coming dilemma that both NASA and Congress will soon have to face once Starship is operational and launching large cargoes and crews to orbit, both near Earth and to the Moon.

That dilemma: What do about SLS and Lunar Gateway once it becomes ridiculously obvious that they are inferior vessels for future space travel?

I think this quote from the article more than any illustrates the reality that these government officials will soon have to deal with in some manner:

[When] the Lunar Starship ever docks with Gateway, the size comparison with Gateway will appear silly and beg the question as to whether Gateway is actually necessary. Does this even make sense? Couldn’t two Starships simply dock with each other and transfer propellant from one to another. Is there really a need for a middleman?

The author, Doug Plata, also notes other contrasts that will make SLS and Lunar Gateway look absurd, such as when two Starships begin transferring fuel in orbit or when a Starship launches 400 satellites in one go, or when a private Starship mission circles the Moon and returns to Earth for later reuse.

All of these scenarios are actually being planned, with the first something NASA itself is paying for, since the lunar landing Starship will dock with Lunar Gateway to pick up and drop off its passengers for the Moon.

The bottom line for Plata is that the federal government needs to stop wasting money on bad programs like SLS and Lunar Gateway and switch its focus to buying products from commercial sources like SpaceX. They will get far more bang for the buck, while actually getting something accomplished in space.

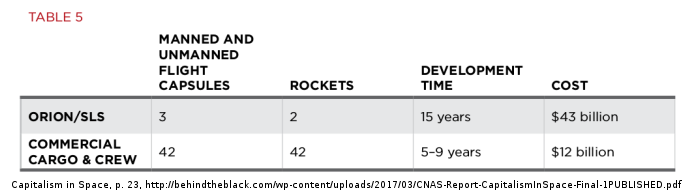

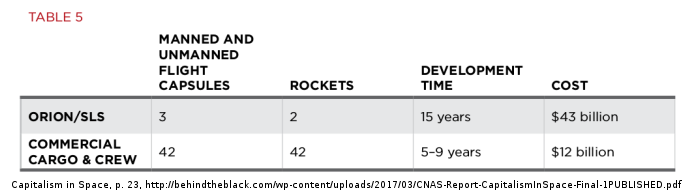

Though he uses different words, and has the advantage of recent events to reference, Plata is essentially repeating my recommendations from my 2017 policy paper, Capitalism in Space [free pdf]. Plata draws as his proof for his argument the recent developments with Starship. I drew as my proof a comparison between SLS and what private commercial space was doing for NASA, as starkly illustrated by this one table:

The government has got to stop trying to build things, as it does an abysmal job. It instead must buy what it needs from private commercial vendors who know how to do it and have proven they can do it well.

If the government does this, will not only save money, it will fuel an American renaissance in space. As we see already beginning to see happen now in rocketry and the unmanned lunar landing business.

On Christmas Eve 1968 three Americans became the first humans to visit another world. What they did to celebrate was unexpected and profound, and will be remembered throughout all human history. Genesis: the Story of Apollo 8, Robert Zimmerman's classic history of humanity's first journey to another world, tells that story, and it is now available as both an ebook and an audiobook, both with a foreword by Valerie Anders and a new introduction by Robert Zimmerman.

The print edition can be purchased at Amazon or from any other book seller. If you want an autographed copy the price is $60 for the hardback and $45 for the paperback, plus $8 shipping for each. Go here for purchasing details. The ebook is available everywhere for $5.99 (before discount) at amazon, or direct from my ebook publisher, ebookit. If you buy it from ebookit you don't support the big tech companies and the author gets a bigger cut much sooner.

The audiobook is also available at all these vendors, and is also free with a 30-day trial membership to Audible.

"Not simply about one mission, [Genesis] is also the history of America's quest for the moon... Zimmerman has done a masterful job of tying disparate events together into a solid account of one of America's greatest human triumphs."--San Antonio Express-News

An interesting essay published earlier this week in The Space Review raises the coming dilemma that both NASA and Congress will soon have to face once Starship is operational and launching large cargoes and crews to orbit, both near Earth and to the Moon.

That dilemma: What do about SLS and Lunar Gateway once it becomes ridiculously obvious that they are inferior vessels for future space travel?

I think this quote from the article more than any illustrates the reality that these government officials will soon have to deal with in some manner:

[When] the Lunar Starship ever docks with Gateway, the size comparison with Gateway will appear silly and beg the question as to whether Gateway is actually necessary. Does this even make sense? Couldn’t two Starships simply dock with each other and transfer propellant from one to another. Is there really a need for a middleman?

The author, Doug Plata, also notes other contrasts that will make SLS and Lunar Gateway look absurd, such as when two Starships begin transferring fuel in orbit or when a Starship launches 400 satellites in one go, or when a private Starship mission circles the Moon and returns to Earth for later reuse.

All of these scenarios are actually being planned, with the first something NASA itself is paying for, since the lunar landing Starship will dock with Lunar Gateway to pick up and drop off its passengers for the Moon.

The bottom line for Plata is that the federal government needs to stop wasting money on bad programs like SLS and Lunar Gateway and switch its focus to buying products from commercial sources like SpaceX. They will get far more bang for the buck, while actually getting something accomplished in space.

Though he uses different words, and has the advantage of recent events to reference, Plata is essentially repeating my recommendations from my 2017 policy paper, Capitalism in Space [free pdf]. Plata draws as his proof for his argument the recent developments with Starship. I drew as my proof a comparison between SLS and what private commercial space was doing for NASA, as starkly illustrated by this one table:

The government has got to stop trying to build things, as it does an abysmal job. It instead must buy what it needs from private commercial vendors who know how to do it and have proven they can do it well.

If the government does this, will not only save money, it will fuel an American renaissance in space. As we see already beginning to see happen now in rocketry and the unmanned lunar landing business.

On Christmas Eve 1968 three Americans became the first humans to visit another world. What they did to celebrate was unexpected and profound, and will be remembered throughout all human history. Genesis: the Story of Apollo 8, Robert Zimmerman's classic history of humanity's first journey to another world, tells that story, and it is now available as both an ebook and an audiobook, both with a foreword by Valerie Anders and a new introduction by Robert Zimmerman.

The print edition can be purchased at Amazon or from any other book seller. If you want an autographed copy the price is $60 for the hardback and $45 for the paperback, plus $8 shipping for each. Go here for purchasing details. The ebook is available everywhere for $5.99 (before discount) at amazon, or direct from my ebook publisher, ebookit. If you buy it from ebookit you don't support the big tech companies and the author gets a bigger cut much sooner.

The audiobook is also available at all these vendors, and is also free with a 30-day trial membership to Audible.

"Not simply about one mission, [Genesis] is also the history of America's quest for the moon... Zimmerman has done a masterful job of tying disparate events together into a solid account of one of America's greatest human triumphs."--San Antonio Express-News

And if we had anti-gravity we wouldn’t need rockets. As for Starship refueling….we’ll see.

“… the coming dilemma that both NASA and Congress will soon have to face once Starship is operational …”

Maybe someone in the government actually noticed this coming and told the FAA to deal with the problem …

They need to focus on Branson.

Honestly, I think we’re at the point where a pretty thick slice of NASA management understands that even a *limited* success for Starship – that it ends up becoming operational, just not as cheaply or frequently as Musk hopes – means that SLS can be dispensed with. And with it, probably, Lunar Gateway and even Orion, too. I think this was certainly Jim Bridenstine’s sense by the end (Bill Nelson, not so much, though he’s handcuffed by inherited policy in many ways). And I think those NASA peeps are pretty confident that SpaceX *will* have a least a limited success with Starship.

And after all, it’s worth noting what Eric Berger has recently observed: NASA really *has* come a long way over the last five years not just in its relationship with SpaceX, but its whole approach to commercial space and how to procure from it. It didn’t come easy; but it did come. Something like CLPS was unthinkable a decade ago.

The problem is, as we all know, those people don’t really write the checks. Congress does. And Congress will have to be beaten over the head a lot harder. Elon needs to just keep racking up the wins.

Kudos to visionary Elon Musk… but we view classical action-and-reaction rocketry, even (perhaps) some equally mechanistic/relativistic “warp drive,” as inherently inadequate for even minimal star-faring.

Think Voyager I launched 1977, now a big 21.87 light-minutes (.365 light-hour) from Earth, heading to our closest star-system Proxima Centauri, distant 4.37 LY: Hurtling outward (sic) at 30 light-seconds per annum, Voyager I will tick our nearest neighbor in a mere 4,441,000 years. By then, of course, our ramping/rutting “naked ape” posterity will have lapsed to evolutionary desuetude. On any meaningful scale, even the most parochial Milky Way environs –nevermind Local Group excursions to Andromeda et al.– are utterly beyond Newton’s reach.

The good news is that Musk & Co. bear to late 21st Century technology as 1820 canal boats do to SR-71s. From c. AD 2030 to 2049, macro-scale quantum entanglement/superposition (“telesponding”), treating cosmic navigational coordinates (“information”) as 100% probable potential energy = i + mc^2! (“factorial”), will instantaneously transpose any mass-point from A to B within our dual-dynamic cosmos’ ever-dilating, non-relativistic Eternal Present interface regardless of spatio-temporal “distance” as causal-geometric physics knows the term.

For anyone born c. 2025, the years to 2124+ will see more transformative advances than all previous four centuries from AD 1600.

Doug Plata wrote in his Space Review essay: “SpaceX is completely rewriting the book when it comes to rockets.”

I would say that truer words were never written, except that others have been rewriting the book, too. Reusability is not so new, as it was tried in the 1990s (as well as with the Space Shuttle). The space industry has been clamoring for lower cost launches for four or five decades, and reusability of the Space Shuttle was supposed to supply it. Low-cost launches are an important part of the book of rocketry. Blue Origin was the first to successfully land a booster rocket, although it was not orbital, but it counts, in the book of reusable rockets. Rapid turnaround times for a reusable rocket and spacecraft may be new in practice, but it has been in the book of rocketry for at least three decades, and longer than that, if we include the plan to refly each Space Shuttle orbiter every two months.

SpaceX was not the first to launch from a private launch pad. That goes to Blue Origin for suborbital rocketry and to Rocket Lab for orbital rocketry.

The Methane/Oxygen rocket engine is not exactly unique either, as Blue Origin has developed their own, starting it in 2012, a year after the Raptor engine hit the drawing board.

Things that SpaceX does that others do not is rapid development, and that isn’t even new in the rocket industry. However, Blue Origin missed that one, even though they beat SpaceX to first landing of a reusable booster, and SpaceX made a museum piece out of their first landed booster rather than demonstrate that it could, in fact, relaunch.

The high angle of attack on reentry is new, but was not surprising. This didn’t create much of a stir in the space industry when they proposed it.

Storing propellant tank end caps and even tank parts outdoors is very new, as the industry has considered such sloppy techniques to be sources of fatal contamination. This certainly seems to be a new rewrite of the rocketry book, but I continue to wonder whether they will store these parts indoors and in cleaner environments once they are out of development and enter production. This may not be quite the rewrite that it seems right now.

That Wonky flip just before landing Starship is certainly new and a rewrite of the rocketry book. Even the Delta Clipper didn’t do a seemingly suicidal high speed flip seconds before landing. At best, Delta Clipper wiggled around a bit at the apex of its last test flight. It took a few tries to show that this landing technique could even be done, and on a large and heavy spacecraft, too.

Up to now, rocket pads and manufacturing/test facilities have been on much larger plots of land. Even their much smaller grasshopper test range was larger, although it did seem smaller than most test ranges.

Robert Zubrin’s book The Case For Mars is not exactly the book of rocketry, but it seems to be where SpaceX was inspired for their goal of going to Mars. Such a goal seems to be more than just a stretch goal — going to the Moon would seem the stretch goal for commercial space companies, as only governments have had the resources to do that, until now. Going to Mars seems like an over-stretch goal, yet SpaceX talks of Mars as though the Moon is just too boring for a return journey. For a private company to talk of going to Mars without a government contract for doing so, that is a rewrite of the rocket industry’s book. Up to now, only Scaled Composites, Virgin Galactic, and Blue Origin have done solely with private funding what only governments have done in the past.

Virgin Galactic, and Blue Origin are going beyond that, again only with private (non-governmental) funding. They are completing privately-funded development of commercial space tourism in space, rather than a zero-g airplane or a “Star Tours” ride at Disneyland. (Yet there are those in Congress, such as Rep. Earl Blumenauer (D-OR), who greedily want to tax the passengers of these privately-developed spacecraft, claiming that “things that are done purely for tourism or entertainment, and that don’t have a scientific purpose, should in turn support the public good.” Next they will want to tax us for watching television or baseball games.)

SpaceX may be rewriting a couple of chapters, but it is conforming to many other chapters, chapters that other companies and countries have ignored up to now, which may make it seem like a rewrite.

“Who could compete with that?”

Plenty of companies. In its rush to develop Starship, SpaceX has left a lot of room for improvement. They have not spent time on optimization, preferring instead to concentrate on becoming operational and generating revenue. The Super Heavy first stage has twice the thrust as the Saturn V and 50% better propellant efficiency, yet Starship can only take the same amount of mass to orbit? That sounds like there is a whole lot of room for a competitor to improve upon.

What I haven’t yet seen is the other companies and countries return to rapid development. Other industries have long ago figured out that getting products to market quickly is vitally important. Somehow, SpaceX is one of the few rocket companies to realize this and is the only heavy lift launch company to be doing this. For a few billion dollars, SpaceX is figuring out how to do new things and how to accomplish old ideas, plus build the needed infrastructure.

I think Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic have won the silly-names competition, but apart from that they are a joke.

It ain’t how early you start to develop a full-cycle methalox engine, it’s when you complete it. Let me know when we see 29 BE-4s hanging under something. I’m not going to be holding my breath.

I wish people would stop using congress as an excuse for what NASA does.

Its not like congress proposes the ideas. They ONLY approve the budget after the ideas are given to them.

If they approve a smelly idea who gave it to them? NASA thats who.

NASA proposed the SLS knowing full well they didn’t even have a job for it. They also knew full well how the suppliers and contractors would work and how much they would insist and a budget increase. Nasa also knew they would want a budget increase to finance research into new tech to build the thing.

NASA has played this game for 70 years. They knew exactly what they were doing and knew exactly who and how to lobby in congress to get it done.

And please don’t blame the Space shuttle for Nasa’s problems. The new it was a cia/military project all along. And they knew that right after its first flight it was a waste of time effort and money. But they kept pushing it it as the do all platform for space. They knew. They are responsible for everything wrong with their own system.

Don’t forget the *other* SpaceX innovation–focusing up front on developing not just the rocket, but the facilities, tooling, and training for mass production, all right from the outset.

A. Nonymous wrote: “Don’t forget the *other* SpaceX innovation–focusing up front on developing not just the rocket, but the facilities, tooling, and training for mass production, all right from the outset.”

This isn’t really an innovation, as other industries have known to do this for a long time, but where rockets are concerned, SpaceX may be the first company to be truly eager to produce a large number of engines and rockets. So this is a rewrite of the book, when it comes to rockets.

“I wish people would stop using congress as an excuse for what NASA does.”

That’s pretty much how it works in reality. The closer you get to HQ/DC the more rarified the air. It’s pretty much just like the Post Office but with rockets, somewhere, sometimes.

pzatchok wrote: “I wish people would stop using congress as an excuse for what NASA does. Its not like congress proposes the ideas. They ONLY approve the budget after the ideas are given to them.”

Of course, the people at NASA are not smart enough to make sure that what they propose has a chance of being funded by Congress. If NASA proposes something that Congress would not fund, then NASA winds up with … nothing. Isn’t this what happened to the Mars mission in the 1990s? NASA proposed; Congress opposed. No Mars mission.

The next new manned project for NASA was Constellation, a decade later, which had a mission to go back to the Moon. When Obama killed that, Congress demanded that SLS be built. Congress demanded. Congress also designed SLS, telling NASA the launch capacity, the engines, and other details that were to be included in the rocket — designed by law.

Budgeting in the U.S. government does not work the way pzatchok thinks. Congress does not approve the budget, it creates the budget. No one else. It is the president who approves the budget, and he only has power to approve or to veto. No other option or power is available to him or to his departments, agencies, or administrations. They must spend money in the ways designated in the budget.

Just as NASA checks with Congress to see what they may authorize, Congress checks with the president to see what he might sign. The president sends to Congress a budget proposal, the implied statement being: “I will sign a budget that looks like this.” Congress may or may not present the president with a similar-looking budget.

Congress has far, far more influence over what happens in America than most people think. Here is an example:

https://behindtheblack.com/behind-the-black/points-of-information/house-nasa-budget-cuts-all-funding-for-lunar-lander-but-adds-billions-for-infrastructure/

NASA has proposed; Congress may oppose. We will see whether a Human Landing System is funded for next year. If not, then maybe Blue Origin, for selfish reasons, has successfully delayed our expansion into the solar system.

Oh, and without a lunar landing method, SLS once again has no mission. A situation that Congress may be about to create, not NASA. NASA asked for the opposite.

“And please don’t blame the Space shuttle for Nasa’s problems. The new it was a cia/military project all along.”

If it wasn’t a NASA project, then that could explain why it was such a problem.

“And they knew that right after its first flight it was a waste of time effort and money. But they kept pushing it it as the do all platform for space. They knew. They are responsible for everything wrong with their own system.”

So, does this mean that after the first flight Congress would have been willing to spend billions of dollars more to make another manned spacecraft? Being a waste of time, effort, and money makes the Space Shuttle seem like a problem (bigger than I had thought), not a solution, so it was a source of problems for NASA after all.

Nasa wanted A space shuttle. Their original proposal was not what we ended up with.

They asked for a huge budget and congress did not agree to fund it. So instead of working with a smaller budget they decided to work with the cia/military in order to get their portion of the funding needed.

Well in order to get the cia/military budget they had to actually increase the size and shape of the Shuttle.

It was designed to recover spy satellites that used film canisters.

A few short years before the Shuttle flew its first flight the reconnaissance satellites were replaced with digital ones no longer needing film.

Instead of dropping the program Nasa used the shuttle to launch everything a cheaper Atlas rocket could have been used for.

SLS will be the very same thing. All dressed up with no job to do.

If more than one of the 29 engines of the Starship booster fails on one of 100 flights, the individual engine is allowed to fail only 3.5 times out of 10,000 ignitions/operating time periods. A high hurdle, I would say. However, if you ask about for 1,000 flights to failure, the permissible failure rate decreases to 3.8 cases per 100,000 ignitions.

pzatchok,

You wrote: “They asked for a huge budget and congress did not agree to fund it.”

You finally get it and agree that Congress is the major source for NASA’s problems, and the Shuttle was so badly compromised that it didn’t do us much good. As you almost noted, the Shuttle nearly killed the rest of the U.S. launch industry and was why Arianespace did so well.

SLS is likewise an expensive system with a low launch rate and no mission, so we can expect it to do even less than the Shuttle to expand our knowledge and use of space.

Questioner,

You pondered: “However, if you ask about for 1,000 flights to failure, the permissible failure rate decreases to 3.8 cases per 100,000 ignitions.”

I think you are assuming that an engine failure means that the launch fails. If SpaceX routinely asks 96% from all engines, then they can get to orbit with the remaining 28 engines providing 100%. It is a good idea to design for failure tolerance.

Edward:

The matter is a little more complicated than you make it out to be. Sure, the Starship, due to its high thrust-to-weight ratio of around 1.5, can tolerate the early failure of a single engine in terms of the cut-off velocity achieved (maybe even two) if the engine has been shut down properly. I.e. it did not explode and it did not damage or destroy neighboring engines, what it is also possible.

Furthermore, no unburned propellant is allowed to flow out permanently from the non-functioning engine, which would lead to a strong decline of final velocity of the booster at stage separation. If the non-functioning engine is in the outer ring, the exactly opposite (good) engine must probably also be switched off in order to keep the total thrust vector of the rocket in a certain range and to ensure the control authority of the rocket, because those engines cannot gimbaled (only the inner ones). This shutdown must be done very quickly. I hope you can see that this is a little more complicated than you thought.

By the way, precisely because of the problems described here, the Soviet moon rocket N1 failed in the end. You couldn’t get it under control quickly enough. However, Starship has one advantage over the N1 missile: All engines will be tested on the launch pad before launch, which should significantly reduce the probability of one of the engines failing compared to the N1 missile.

Questioner,

I understand how complicated it is. You even oversimplified, in that the opposite engine need not be shut down at all. Notice that two recent launch attempts with far fewer engines each had an engine failure yet were able to maintain their climb for quite some time despite an even greater imbalance than Super Heavy would experience. Neither had to shut down the opposite engine. For Super Heavy, one shutdown engine means that the other engines have to be adjusted to compensate with minimal gimbaling compensation needed.

Engines are heavily instrumented so that they are shut down and propellant supplies stopped well before they become a danger to the rocket. It is part of the engine management system.

The N1 rocket had a poorly designed engine management system, and this is responsible for either three or for all four failures. One time, the management system shut down all but one engine rather than concentrate on the problem engine. Many lessons have been learned during the intervening half century.

Edward:

You may overlook the fact that with the Starship booster, only the inner 9 engines are gimbaled, but not the outer ring of 20 (22) engines, so a comparison with the other two launch vehicles (Astra and Alpha), which have all 5 or 4 engines are gimbaled is difficult. The flight of Alpha in particular showed what the loss of control authority means. The moment the rocket entered the transonic area, it became unstable and had to be detonated.

It seems to me that the Starship launcher system is aerodynamically much more unstable than the two mentioned launchers due to the large braking surfaces arranged very far in front of it, and therefore already a good part of the reserves of the attitude control or control authority of the rocket due to an unfavorable position of the aerodynamic center of pressure in the relation to the center of gravity of the rocket will be used up. The aerodynamic shape of the Astra rocket (wide body at the lower end) indicates in contrast to a positive aerodynamic stability margin, which results in greater control reserves, which can be used up in case for the failure of an engine.

We will learn over time how good the Starship design is.

Questioner,

You pondered: “It seems to me that the Starship launcher system is aerodynamically much more unstable than the two mentioned launchers due to the large braking surfaces arranged very far in front of it …”

Or they may be able to be used as additional stabilizers. You may be underestimating the designers. The first test launch will have the booster-stage’s grid-fins deployed during launch, rather than folded along the sides. They are pretty far forward, so SpaceX clearly is willing to fly with the center of pressure farther forward than the center of mass. (For those who don’t know, airplanes and rockets in the atmosphere are self stabilizing when the center of mass is forward of the center of pressure, the effect of the wings and tail surfaces. They are sort of like arrows.) Keep in mind that the center of mass moves over time, where later in the first stage’s flight it moves forward, toward the upper stage.

I also would not worry so much about nine gimbaled engines, as it is still more than four or five, giving them quite a bit of force to work with. The Firefly Alpha has only four engines, and they are limited in their gimbal motion, complicating the control. When they lost one engine, they may not have had enough residual control to successfully pass through the transonic regime.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=erXrnvyuhJs#t=280

Questioner,

You pondered: “It seems to me that the Starship launcher system is aerodynamically much more unstable than the two mentioned launchers due to the large braking surfaces arranged very far in front of it …”

You may be underestimating the SpaceX engineers. Not only do they already know that Starship has a center of pressure farther forward than usual, but they are planning to launch the first test launch with the booster’s grid fins deployed rather than folded along the fuselage. These fins alone would bring the center of pressure far forward, possibly forward of the center of mass. (For those who do not know, feathers on an arrow, tails on an airplane, and fins on a booster stage help keep the center of pressure (e.g. fin area) behind the center of mass. This makes them self stabilizing with the forward end remaining forward.) SpaceX is already planning for an unstable ride through the atmosphere. Keep in mind that as a rocket expends propellant, the center of mass changes.

I would not worry so much about nine gimbaled engines, because that is already more than the four and five on the other rockets, giving Starship more force for control. Alpha had limitations on their gimbals that reduced their ability to control the rocket once the engine failed. Scott Manley mentioned this in his analysis of the test flight:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=erXrnvyuhJs#t=280