The long term ramifications of SpaceX’s crew Dragon on the future of the human race

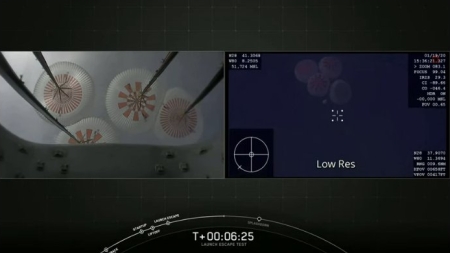

Crew Dragon soon after its parachutes had deployed

during the launch abort test.

The successful unmanned launch abort test by SpaceX of its crew Dragon capsule today means that the first manned flight of American astronauts on an American rocket in an American spacecraft from American soil in almost a decade will happen in the very near future. According to Elon Musk during the press conference following the test, that manned mission should occur sometime in the second quarter of 2020.

The ramifications of this manned mission however far exceed its success in returning Americans to space on our own spacecraft. NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine touched upon this larger context with his own remarks during the press conference:

We are doing this differently. NASA is going to be customer, one of many customers. I want SpaceX to have lots of customers.

Bridenstine is underlining the real significance of the entire commercial program at NASA. Unlike every previous manned space project at the space agency, NASA is not doing the building. Instead, as Bridenstine notes (and I recommended in my 2017 policy paper Capitalism in Space), it is merely a customer, buying a product built entirely by a private company. And while NASA is involving itself very closely with that construction, it is doing so only as a customer, making sure it is satisfied with the product before putting its own astronauts on it.

NASA also does not own this product. As Bridenstine also notes (and I also recommended in Capitalism in Space), SpaceX owns the product, and once operational will be free to sell seats on crew Dragon to private citizens or other nations.

This different approach also means that NASA is not dependent on one product. From the beginning its commercial crew program has insisted on having at least two companies building capsules — Dragon by SpaceX and Starliner by Boeing — so that if there is a launch failure with one, the second will provide the agency with redundancy.

Bridenstine was very clear about these points. He wants multiple manned spacecraft built by competing American capsules, both to provide the government with redundancy but also to drive innovation and lower costs.

SpaceX of course is the quintessential example of how to lower costs.

Two first stages land simultaneously during

first Falcon Heavy launch.

Its effort to develop reusable rockets in the past decade has slashed the cost for a rocket launch from about $200 million to $50 million or less, depending on circumstances. That cost is going to drop even lower in the coming years as they begin reusing a small number Falcon 9 first stages rather than building and discarding a new one with each launch. For example, the first stage used on today’s launch abort was being flown for the fourth time, making it one of three SpaceX first stages that has flown that many times. In coming years SpaceX expects first stages to be reused far more than this, with the goal of a turnaround of less than a day.

A first stage comprises about 60% of the cost of a launch. The consequences of this high reuse by SpaceX will be that they will need to build very few first stages, lowering their costs dramatically. Since no one else has this capability, SpaceX will thus be able to undercut the price of any other launch company in the world, and yet maintain a far higher profit margin, extra money that they can funnel back into the company for further development.

Consider how this situation applies to selling seats on Dragon to private customers. The Russians have been charging about $20 to $30 million per seat to fly private citizens on their Soyuz rocket to ISS. Since both Dragon and Starliner can carry four astronauts each, and the American crew contingent on ISS has traditionally been about three, this means that both spacecraft will frequently have room for a private customer.

NASA will pay most of the cost for the launch, which means both SpaceX and Boeing will be able to charge cut-rate prices that will undercut the Russians. SpaceX however will easily be able to undercut Boeing, as it will be using reusable rockets whose individual launch costs will be far less. In fact, SpaceX will likely be able to launch an entirely private mission, without NASA’s help, and charge its four private astronauts only about $10 million each and still make a profit. Very quickly the company will grab most of the orbital space tourism business from the Russians.

Moreover, if Russia and Boeing wish to remain in this business they will have to compete. They, as well as every other space-faring nation (China and India come to mind) will be forced to develop their own reusability. Eventually, the competition will force everyone to build their rockets and spacecraft like airplanes, with costs dropping as fast as computer memory has grown with time.

None of this factors in the possibilities suggested by SpaceX’s effort to develop its completely reusable heavy lift rocket dubbed Super Heavy/Starship. According to recent comments by Elon Musk, each Starship is being designed to have a lifespan of 20 to 30 years with a cost of $2 million per launch. And for that money it will place more than a hundred tons in orbit, five times that of a Falcon 9!

The ramifications of all this are immeasurable. Because of SpaceX’s push to lower costs, we appear to be on the cusp of making it possible for the human race to leap from planet Earth.

From an American perspective however this situation is even more profound. It appears that the United States is presently positioned to be the world’s number one provider of manned space vehicles, capable of putting humans in space at the most affordable prices. As the human race begins the first exploration and colonization of the planets and asteroids, this fact is going to place this country in the dominant position of that exploration and colonization.

It also means that this country will have the opportunity to make dominant in those first colonies our principles of freedom, individual rights, free speech, rule by law, and democracy. This fact is probably the most profound consequence of SpaceX’s success today. It increases the odds that untold generations in the future will have a chance to live under these humane conditions.

This is an opportunity that we in America must not miss. While it will benefit us here on Earth in ways unimaginable, the benefits it will bring to future generations cannot be measured.

We must take this chance by the hand and run with it.

On Christmas Eve 1968 three Americans became the first humans to visit another world. What they did to celebrate was unexpected and profound, and will be remembered throughout all human history. Genesis: the Story of Apollo 8, Robert Zimmerman's classic history of humanity's first journey to another world, tells that story, and it is now available as both an ebook and an audiobook, both with a foreword by Valerie Anders and a new introduction by Robert Zimmerman.

The print edition can be purchased at Amazon or from any other book seller. If you want an autographed copy the price is $60 for the hardback and $45 for the paperback, plus $8 shipping for each. Go here for purchasing details. The ebook is available everywhere for $5.99 (before discount) at amazon, or direct from my ebook publisher, ebookit. If you buy it from ebookit you don't support the big tech companies and the author gets a bigger cut much sooner.

The audiobook is also available at all these vendors, and is also free with a 30-day trial membership to Audible.

"Not simply about one mission, [Genesis] is also the history of America's quest for the moon... Zimmerman has done a masterful job of tying disparate events together into a solid account of one of America's greatest human triumphs."--San Antonio Express-News

As a taxpayer, the very thought of Americans, launching to space, from American soil, on American rockets, powered by Russian engines, and solid fuel rockets (I remember Challenger), the entire stack being expendable, littering the ocean floor, while charging 3-4 times more than SpaceX for that privilege is totally ludicrous and unAmerican.

Maybe Bigelow will launch a private space habitat now

Robert,

Thank you for that analysis. This is not by any means a done deal that America and freedom will dominate space, because China has its own eyes on dominating the space economy in the next thirty years:

https://www.rt.com/business/472554-china-space-economic-zone/

“[China] is considering developing commerce beyond our planet and wants to create an economic zone in cislunar space by 2050. … The project could bring in around $10 trillion for China.”

It looks to me as though we are in a new space race between the free world and the communist world, the United States and other countries vs. China. This time, however, rather than two top-down centrally-controlled national programs competing against each other, will see a competition between the nation of China (a centrally controlled national space program performing what China’s government wants) and a collection of free market capitalist companies as they choose goals that bring in revenues by selling goods and services to customers that want them. Not all these companies will be American, as there are a growing number of companies around the world entering the free market competition in space.

Your comparison of the price to space is telling. When governments were making the decisions, access to space was expensive. After a decade with just one company having the liberty and freedom to make its own decisions about space access, prices have dropped dramatically. Imagine what will happen when even more competition is introduced by such companies as Blue Origin and Reaction Engines (Skylon launch vehicle).

If a Starship launch can put as much into orbit at the low price that Musk suggested, then we can take things to space for about the price of shipping them overnight to a city on Earth. To do this only a couple of decades after a commercial company enters the launch industry as a free market capitalist entrepreneurial company.

How amazing is that?

One thing that puzzles me is how many people still think that we must choose between going to the Moon and going to Mars. This is thinking that assumes that NASA is going to do these things. In reality, NASA already has heavy competition from just one company, SpaceX, and as more companies join the competition, NASA will become less the doer of great things and more of a repository of knowledge of how great things get done. Even now, NASA is mentoring many companies in space design and operation. It continues to learn from the entrepreneurial companies that it mentors, because these companies are starting to do their own great things.

What was seen as impossible or improbable just two decades ago are now coming true and are eagerly awaited to come to fruition. Reusable inexpensive rockets are now so common that people no longer watch their launches in the same numbers (similar to Apollo missions). Small satellites are now so common that new companies have formed just to supply miniature parts and subsystems for these satellites. Going around the Moon is an actual early commercial goal for Starship. Going to Mars is seen as a probability for SpaceX. Commercial space stations, often called habitats, are goals for at least four companies. Huge constellations of small satellites are now being put into orbit. All these are great things being done by commercial space companies.

Spaceflight historian Amy Teitel argues that Apollo led to our slow expansion into space. I agree:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e0ERXwhn-5w#t=1259

“Yet somehow NASA’s identity is still wrapped up in Apollo. Its value, perceived mostly by the average person, has been so wrapped up in human spaceflight, but not just that, of flagship human missions. We have this notion that spaceflight matters when the human is central. Presidents are not immune to the influence of Apollo when laying out their own space policy, and many have sought to have their own ‘Kennedy moment.’”

For half a century, people still think that space is too expensive and difficult for individuals or companies to do, even after a small team of people at Scaled Composites, in 2004, successfully put a manned spacecraft into suborbital space, twice within two weeks. This rapid reuse of a spacecraft went beyond the capability of any national space program. Two decades later, it is hard for most people to change their thinking about how we are going to do space in the future. Central control and twenty-billion dollar budgets for flagship human missions seem to be the way most people think we must go, but free market capitalist companies are doing the same things for small fractions of the cost that NASA does it for.

Again, how amazing is that?

born01930,

Bigelow has, in past years, suggested that they intend to begin space habitat operations a couple of years after the expected (and slipping schedule of) first operational commercial manned mission to the ISS.

I expect Bigelow’s habitats to be a major part of the economy and industry that is performed in space in the coming decade. The habitat/space station industry is expected to be so lucrative that there are other companies seriously working on their own space habitats: Axiom Space, Ixion, and Sierra Nevada. Northrup Grumman’s Orbital ATK acquisition also has a cargo ship could become a manned habitat, and Boeing and Lockheed Martin have experience building ISS modules and hardware, so they may enter this market by the end of the decade.

https://www.space.com/34377-private-space-stations-may-take-flight-in-2020.html

ULA also has a vision for the future, called Cislunar 1000. They see, in the next 30 years, a space economy of almost $3 Trillion per year with a population of 1000 people living and working in space. We are behind on their schedule, but largely because it took so long to start commercial manned space operations:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uxftPmpt7aA (7 minutes)

These visions suggest that the space economy will grow quickly, and that an aggregated revenue of multiple tens of trillions of dollars is possible. Thus the free market capitalist space economy is projected to be larger than China’s centrally-controlled space economy.

Thirty years may seem like long term in an individual human’s perspective, but it is short term in historical perspective. With luck, the spacefaring generations of the future will realize that the American experiment of freedom, liberty, and smaller government results in the most productivity and attracts the most people and talent. When they compare early America with the rest of the world and the more recent overbearing America, I think this will be clear. Certainly it will be clear when they compare America’s centrally-controlled first half-century in space with her free market capitalist driven second half-century in space.

When government is in charge, all we get is what government wants; when We the People are in charge, we get what we want. This concept is the value of the great American experiment in liberty and freedom.

Since both Dragon and Starliner can carry four astronauts each, and the American crew contingent on ISS has traditionally been about three, this means that both spacecraft will frequently have room for a private customer.

Actually, that won’t be possible, since NASA plans to make use of all four seats on every Starliner and Dragon operational flight (with both its own astronauts, and those of participating foreign space agencies on ISS, like ESA, JAXA, et al), which in turn will allow the ISS to increase regular crew size to 7, rather than 6, astronauts, which in turn will at least double science work done on the station. Link: https://www.nasa.gov/feature/commercial-crew-missions-offer-research-bonanza-for-space-station

Rather, it looks (for now) like any future private tourists or corporate personnel would be flown up on separate Starliner or Dragon flights as a general rule – most likely, it seems, to any new commercial module attached to the space station, or ones operated as free flying stations.

Moreover, if Russia and Boeing wish to remain in this business they will have to compete.

Alas, there’s little evidence to date that Boeing is really interested in this market.

(It’s not *impossible* that they will ever fly commercial or private customers; it’s just that there’s no evidence that they’re really going to make active efforts to pursue this market.)

Boeing seems to be treating Starliner as a vehicle the operate for NASA, to NASA specs, and not for anything or anyone else. They would just as happily (actually, more happily), built it as a NASA cost-plus vehicle.

Still, for all the disappointments that come with Boeing, the fact remains that by the end of 2020, half of all operational orbital crew vehicles in the world will be operated from American soil, and that’s a very good thing.

Richard M: What is NASA’s plans now might not be their plans in the future, especially when faced with a profit-oriented private market and an administration dedicated to expanding that market.

Similarly, what Boeing plans now might not be their plans in the future, especially when faced with serious management problems that are cutting into their bottom line, and a potential profit center (manned space) that would also buy them gigantic positive press.

Hello Captain Emeritus,

As a taxpayer, the very thought of Americans, launching to space, from American soil, on American rockets, powered by Russian engines, and solid fuel rockets (I remember Challenger), the entire stack being expendable, littering the ocean floor, while charging 3-4 times more than SpaceX for that privilege is totally ludicrous and unAmerican.

I completely share your dismay, and it’s only an inherent optimism on my part that tends to focus on the fact that at least *one* of the two Commercial Crew contractors is giving us low cost, reusable, fully indigenous orbital crew capability. It could have been worse, you know. There was serious pressure on the Hill in 2012-14 to force NASA to downselect to one contractor, and we all know who *that* would have ended up being.

That said, the situation for Starliner will improve a little by 2022, when it starts flying on ULA’s Vulcan instead of Atlas V. First, it will cost a little less than Atlas V, but also, it won’t be using Russian engines.

And there is always the possibility that in the next phase of Commercial Crew, Sierra Nevada’s Dream Chaser might possibly get a third contractor award, which would give the U.S. a very nice mix of orbital crew capabilities.

Hi Bob,

What is NASA’s plans now might not be their plans in the future, especially when faced with a profit-oriented private market and an administration dedicated to expanding that market.

Oh, I don’t pretend to any special inside knowledge. I just know that this has been the constant refrain of both the last and present administrations: “We want to increase to 7 crew so that we can max out the science done on ISS.” NASA under Bolden, Lightfoot, and Bridenstine have never wavered from that line. With only six crew, almost all the man hours are sucked into just doing basic maintenance and operation on the station, and little time is available for research.

Now, that said, that doesn’t mean that there won’t be non-government customers flying to ISS. I just expect that, initially, it will happen on Soyuz (again) because Roscosmos is getting desperate for hard currency, and then the effort will be made to add a commercial module to the USOS by Bigelow or whoever, as a way to accommodate private astronauts on separate flights. In short, doesn’t have to be “either/or,” but “both/and” – NASA and its ISS partners get the crew size up to the seven they have always wanted, but now they would have the capability to have *even more* come to visit the station on a commercial capacity.

What is it about the SpaceX cult that requires members to not only love SpaceX but also to hate Boeing and ULA?

The Starliner engines are made by Aerojet Rocketdyne, not Russia, and Boeing only charges a few percent more than SpaceX does for the service.

https://forum.nasaspaceflight.com/index.php?topic=35680.msg1259026#msg1259026

Just the opposite. It is SpaceX that appears to be uninterested in commercial Crew Dragon flights — instead focusing on Starship — while Boeing is actively pursuing commercial Starliner seats. As of about a year ago, Boeing’s NASA configuration had a fifth seat for a commercial astronaut while SpaceX’s NASA configuration had only four. Boeing reportedly has an agreement with NASA to be able to sell that fifth seat, and they have a public agreement with Space Adventures.

I don’t know if anything will come from it, but the effort is there.

Oh, and the Boeing’s commercial crew contract is firm, fixed-price, just like SpaceX’s.

Correct. Boeing’s Starliner is re-usable, in large part because it lands on land. SpaceX’s Crew Dragon does not and is not. Why do I suspect you meant it the other way around?

There are no public signs that Starliner will fly on Vulcan in 2022, or anytime during the CCtCap contract. I wouldn’t be surprised if Boeing offered Starliner on Vulcan for the next phase of commercial crew, but nothing has been made public yet that I’m aware of.

Hello mkent,

The Starliner engines are made by Aerojet Rocketdyne, not Russia, and Boeing only charges a few percent more than SpaceX does for the service.

I thought – we were all aware of that. I think your confusion here is because Captain Emeritus and I were talking about the Atlas V, not the Starliner, in this connection. It’s the Atlas V first stage that uses Russian Energomash RD-180 engines – and gets dumped into the ocean after every launch.

It is SpaceX that appears to be uninterested in commercial Crew Dragon flights — instead focusing on Starship — while Boeing is actively pursuing commercial Starliner seats.

Are they? Because I’ve heard just the opposite. Do you have any links? It would be great to see it happen, if so.

As for SpaceX, obviously much of their future plans are wrapped up in Starship at this point. But they also went to considerable lengths to design an interior with aesthetics and ergonomics in mind; and more to the point, they *have* been in discussion with other parties about flying on Dragon. On this point, Elon Musk’s evasive comment, which amused Jim Bridenstine, at the press conference this afternoon was telling: “We have nothing to publicly announce at this time.”

Oh, and the Boeing’s commercial crew contract is firm, fixed-price, just like SpaceX’s.

This is certainly true. Of course, this didn’t stop Boeing from demanding – and obtaining – $287 million in supplementary funding, which triggered criticism from the NASA OIG just a couple months ago. “In our judgment, the additional compensation was unnecessary”: https://oig.nasa.gov/docs/IG-20-005.pdf

Correct. Boeing’s Starliner is re-usable, in large part because it lands on land. SpaceX’s Crew Dragon does not and is not. Why do I suspect you meant it the other way around?

Because I did, and because – again – Captain Emeritus and I were talking about the *boosters*, not the crew vehicles: Falcon 9 is reusable (or at least, its first stage is), and Atlas V is clearly not.

Starliner *is* designed for reusability of the crew capsule, and that *is* an encouraging development (and I was impressed to see Boeing propose it in the first place, even though NASA did not require it). Of course, it also throws away the service module and the heat shield (in contrast to Dragon, which only disposes of the trunk), so clearly reusability only goes so far here.

As for Crew Dragon, you are correct that SpaceX does not plan to reuse these for crew flights to ISS. However, it does plan to reuse them for cargo flights under the CRS-2 contract, at last check. There is reusability (or at least, refurbishability) in play here, it’s just for the cargo flights instead of the crew flights.

There are no public signs that Starliner will fly on Vulcan in 2022, or anytime during the CCtCap contract.

Starliner has been designed to be compatible with Vulcan from the outset (or at least, since Vulcan development began in earnest), and Boeing and ULA have both been talking about switching over to Vulcan for the past four years. For example: https://spaceflightnow.com/2015/04/18/ula-sees-clean-handover-of-boeing-crew-launches-to-vulcan-rocket/

I’ve not heard anything about when the first Vulcan flight will be. But it doesn’t sound like they’re waiting until Phase II of Commercial Crew, either – unless, of course, Vulcan development is delayed *that* far back, which seems very unlikely to me. Clearly, Boeing and ULA would both prefer it to happen sooner rather than later, not least because Vulcan is going to be cheaper to operate.

SpaceX however will easily be able to undercut Boeing, as it will be using reusable rockets whose individual launch costs will be far less.

——————

I believe NASA requires new Falcon 9 boosters for Commercial Crew flights. Falcon 9 are probably still cheaper brand new than the Atlas V rocket.

Also the Dragon is designed to be fully reusable, however NASA wants brand new capsules for Commercial Crew (if they land in water) so SpaceX will reuse Commercial Crew capsules for the Commercial Cargo contract.

I appreciate the historic implication this post highlights. I think that the establishment of humanity’s first permanent foothold off Earth is the prize that history will record as what was most important at this time.

We could slowly achieve that via a permanent NASA-led science base on the Moon with private habitats attached and growing into a settlement. But more likely will be the Starship delivering large amounts of cargo and passengers for a much more rapidly growing settlement.

Only about 20% of the passengers would be American if no favoritism was shown. An international (i.e. UN-like) colony wouldn’t necessarily promote values consistent with the principles of liberty. So that’s why I think, in the early years, there should be a public-private program between NASA and SpaceX to establish an American-led colony and infrastructure before opening the floodgates to private individuals from the rest of the world.

– DevelopSpace.info/leadership

– DevelopSpace.info/history

– DevelopSpace.info/international

– DevelopSpace.info/countries

It’s good that the national disgrace of hundreds of millions to fly Americans on Soyuz is finally going to end.

I get the desire for redundancy, but Boeing has become a joke and wouldn’t be relevant without continuing corporate welfare. When commercial crew is concluded, I’m sure Mr. Z will post the money paid vs. results for both companies.

I read that SpaceX would retire Falcon9 once Starship was up and running. I would hope the falcon9 side of the business will be sold to some entrepreneur and kept going as long as there’s a market. But they may be thinking Starship will also handle Falcon9’s work. Quick search found Elon’s tweet, which may be the source of the articles on retiring Falcon.

SpaceX will prob build 30 to 40 rocket cores for ~300 missions over 5 years. Then BFR takes over & Falcon retires. Goal of BFR is to enable anyone to move to moon, Mars & eventually outer planets.

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) May 13, 2018

One of the downsides of keeping up with so many space sites every day is after a while you forget where you read things. I’ll keep my eye out.

But the gist of it is that as of about a year ago, Boeing’s NASA configuration had five seats, while SpaceX’s had only four, and Boeing had permission to market the fifth seat to non-NASA customers. This is much more recent than the contracts Boeing signed with Space Adventures and Bigelow early in the Commercial Crew program. I haven’t heard of any takers, so maybe nothing comes of it, but they are marketing it.

I don’t think that’s true any more. From a previous NASA press conference, I seem to recall that the CRS-2 cargo variant is too different from the CCtCap crew variant to allow that to happen.

Starliner is designed at a high level to be launch vehicle agnostic. However, detailed analysis and wind tunnel testing is required for each launch vehicle, and the results of that testing can affect the Starliner design. (For example, the aeroshell and perforated disk required for the Atlas V may not be required for other launch vehicles.) This isn’t unusual. Many NRO payloads have similar issues and require three years of analysis before launch on a new launch vehicle. This analysis can run up to eight or nine figures, which is one reason why the NRO doesn’t always chase the lowest launch cost.

Your article, while interesting, is almost five years old. Since then, the analysis and testing I mentioned above has been done, and the Starliner design has been modified with the perforated disk, aeroshell, and probably other things which tie Starliner to Atlas V until the analysis and testing can be done for a new launch vehicle. The expense of that will dictate that it probably will not occur for only one or two launches. I predict Boeing will want a block buy of several additional launches before abandoning the Atlas V.

This is just another case where marketing idealism deviates from the realities of the aerospace industry. SpaceX had a similar issue with propulsive landing. NASA didn’t — couldn’t — nix it. They could only dictate SpaceX not test it on their flights. But there isn’t a big enough market outside of NASA for SpaceX to pay for the testing it would require.

Getting back to Starliner re-usability, Boeing is only building two vehicles to fly their eight contracted flights, so that part of it is a done deal.

I thought one of the reasons Dragon crew didn’t dry land was because NASA demanded it.

I thought the original intention was for the draco escape rockets to double as landing rockets if they were not needed on a launch.

They were testing their hover capability.

No need for landing legs just replace the heat shield like they do on every flight anyways.

NASA wanted water landings because thats all they trust.

I thought one of the reasons Dragon crew didn’t dry land was because NASA demanded it.

More accurate to say that the testing needed for NASA to certify it was going to take SpaceX too long and cost it too much, and so SpaceX abandoned it for a parachute landing system. It sounds like NASA was theoretically open to it, but wanted a heavy load of testing before they’d risk trying it.

Considering all the parachute testing NASA is or was demanding of Space X, I would say a propulsive landing would have taken 10 times as much testing.

But I wonder if Space X can try a propulsive landing on a garbage return trip? Or on any private trip. I would try it at least once. We know they can hit a barge.

NASA wants a brand new passenger capsule for every trip because they do not think a once dunked capsule will be safe enough for passengers. But they are willing to reuse them for cargo. Which requires them to be pressure safe. Hold atmosphere.

Let a re-used cargo capsule work 5 or 6 times safely and NASA will change its mind. But in the mean time they will have wasted hundreds millions of dollars they could have saved.

Regarding the 4 person crew capacity… ISS was designed to have a 7 crew compliment. Because NASA never built a crew return vehicle, as originally conceived, ISS has been reliant on 3 person crewed Soyuz vehicles for emergencies. 2xSoyuz meant 6 person crew. By design, ISS has so much need for maintenance and science. Fewer crew didn’t mean less maintenance, but less science. With Dragon and Starliner, NASA will now be operating ISS to its design. It has only taken nearly a generation.

IIRC, the problem with propulsive landing for crew Dragon was that landing legs would have had to deploy through the heat shield. NASA wouldn’t buy off on compromising the integrity of the heat shield.

mkent,

Re: Reuse of Crew Dragons for CRS-2 cargo missions

I don’t think that’s true any more. From a previous NASA press conference, I seem to recall that the CRS-2 cargo variant is too different from the CCtCap crew variant to allow that to happen.

There’s little out there on this, but yes, it looks like back in July, SpaceX (via Jessica Jansen) indicated that CRS-2 cargo missions would be using special built cargo versons of Dragon 2, which would lack (among other things) Super Dracos, control panel, and life support. They will no longer be modified Dragon 2 capsules previously flown on crew flights. Instead, it will be the cargo versions which will be reused, each one to be certified for five flights. So I stand corrected. SpaceX has been changing plans more rapidly than I could keep up with.

What will be done with the crew version Dragon 2 after their flights is unclear, but I have heard that some systems might be reused on new Dragon 2’s built for future cargo or possibly even crew flights. I don’t have details on that, however.

So let me concede that at least with regard to crew capsules (as opposed to rockets), Boeing has something of a leg up on SpaceX, albeit “refurbishable” is probably the better word, since they have replace the heat shield, backshell, air bags, and (of course) the service module, which includes thrusters, tankage power systems, etc..

But here is the part that gets me: even with such extensive use of reuse, Boeing Starliner crew flights are now estimated by NASA’s OIG as costing $90 million per seat – which is not only more than the $55 million estimated for SpaceX, but even the $80 million presently being paid by NASA for Soyuz seats. If that’s the case, I’d sure hate to see what Boeing would cost if they weren’t reusing *anything*. Link: https://arstechnica.com/science/2019/11/nasa-report-finds-boeing-seat-prices-are-60-higher-than-spacex/

[Don’t get me wrong: I’d rather pay Boeing $90 million a pop to launch astronauts to and from ISS than pay $80 million to Dmitri Rogozin and friends. We need to be launching from U.S. soil with U.S. vehicles. But we have to be clear that this isn’t saving NASA money, either. Because it clearly is not.]

Leland,

By design, ISS has so much need for maintenance and science. Fewer crew didn’t mean less maintenance, but less science. With Dragon and Starliner, NASA will now be operating ISS to its design. It has only taken nearly a generation.

Exactly so.

And I think NASA is right to prioritize getting ISS crew size up to 7. Science is what it’s built for (however inadequately after the cancellation of valuable modules like the Centrifuge), so we should be getting max value out of the vast tax dollars this thing cost to build and operate. Commercial capabilities have to come after that – but they should come, just the same.

In any event, I don’t think ISS life support could easily handle more than 7 people for long periods of time anyway, so I really do think what is going to have to happen is the addition of a large commercial module (by Bigelow, Axiom, Sierra Nevada or whoever) for space manufacture/research/tourism to the station, with its own life support facilities and docking port, and then you would see Boeing and/or SpaceX doing separate commercial flights up to it. It will surely be a few years at least before that happens, and that means it will be creeping up on end-of-station-life; but that could still be a valuable bridge to commercial LEO stations, possibly using that same commercial module as a detached free flight facility.

Starting out with “SpaceX cult” sort of invalidates everything you write subsequently, doesn’t it?

I covered this when Robert first reported on this IG report. The gist of it is that the IG report is very misleading, because neither Dragons nor Starliners are sold by the seat, but by the flight.

If I recall correctly way back from contract award, each CCtCap contract has three CLINs: 1) development of the respective commercial crew system, which included an unmanned and a manned test flight 2) from two to six operational flights, and 3) special studies. The optional CLIN 2 flights (all since awarded for each contractor) were, I think, costed out by flight and fiscal year.

I believe what the IG did was take each contractor’s respective CLIN 2 cost and divide by 24 (six flights of four astronauts each) to arrive at the “per seat” cost. However, each commercial crew vehicle can carry seven seats. NASA instead prefers to ferry only four astronauts at a time to the ISS and fill the remaining three seats with cargo, presumably because they value the additional cargo more than the additional crew. That’s an operational decision by NASA, not a restriction on either commercial crew vehicle.

Mind you, NASA has a good reason for the four-crew / three-cargo split: the USOS life support system can only support a crew of four long-term. However, it can support (I think) up to 13 for short handover periods, so NASA could use either vehicle to ferry a seven-man crew to the ISS for short-term science or maintenance tasks if it chose to do so. Again, not doing so is an operational decision by NASA, not a restriction on either vehicle.

Think of an air cargo analogy. The 747 can be ordered either in an all-passenger, all-cargo, or a “combi” version split between cargo and passengers. It would be unfair to say the 747 Combi has twice the per-seat cost of the 747 passenger variant since the flight cost is the same, but it has only half as many seats.

Anyway, one of the reasons Boeing’s fifth-seat proposal interests me is to see how NASA handles this. Who is going to be allowed to fill it? How will costs be allocated? Presumably Boeing will have to provide something extra in order to “buy” the seat back. How will that work? It’s those kind of transactions that can look messy from the outside but are pretty routine in the commercial world.

Hopefully despite all this, we can agree that with the USOS crew going down to one in April and zero in September, getting both Dragon and Starliner operational quickly is in the nation’s interest.

Oh, one more thing….

Some of the possibilities the commercial crew vehicles open up are these:

1) Tourist or international partner flights, of course.

2) Flying additional crew during the direct handover flights for high-priority science or maintenance tasks.

3) I’d like to see NASA investigate having Boeing take over direct maintenance of the USOS portion of the ISS, which would necessitate Boeing astronauts flying a certain percentage of the seats for that task and leaving the NASA seats as science-only. If structured properly, Boeing would have an incentive to maximize the uptime of station systems and their availability for science. Military logistics contracts are often structured this way (e.g. the C-17 Performance-Based Logistics contract, where Boeing gets paid based on the mission readiness rate).

4) NanoRacks was recently overheard at a space conference as saying they’re in negotiations to have a NanoRacks astronaut on the station from time to time to perform commercial experiments. NanoRacks has purchased astronaut time from NASA, but apparently they have more man-tended experiments than they have astronaut time to tend to them.

With opportunities like these, Commercial Crew could be the bridge program between government manned spaceflight and commercial manned spaceflight. Which I think was Robert’s original point, though he limits it to SpaceX while I don’t.

mkent: I find your comments educational and helpful. However, you misread my essay when you wrote that I limited the future to SpaceX. I only was noting that SpaceX has a very big advantage at the moment, one that should encourage others to step up to the plate to compete.

mkent,

Applauding the SpaceX accomplishments does not equate to being in a cult. I read the essay as addressing private/commercial systems as the new way to go, as opposed to “of the Gov, by the Gov, for the Gov.” Competition and free market access is the future.

You also said SpaceX does not seem to care about Commercial Crew.. But they may be the first to actually do it in March, passing the last hurdle two days ago. Confused. And, Is that really that bad?

I think you confuse public concerns about Boeing in general with “hatin” on them. They have some problems. They just asking for a 10Billion dollar loan to cover the 737 problem (on CNBC this morning). They fired a CEO, they may face additional lawsuits. And on the Starliner test flight, they made a simple error. One that should have been caught. These are legit concerns. I doubt anyone here wants to see the Starliner program collapse, however.

To anyone who may know:

How much is Boeing/ULA open to outside users or are they only going to fly NASA?

NASA does not want to re-use a dunked Dragon. Can they stop them from putting up a pilot and three tourists in a re-used Dragon for an orbital tourist flight? Or for a non-NASA science flight?

Sippin_bourbon: To answer your last question, NASA cannot stop SpaceX from flying a private manned flight on Dragon, nor apparently does it want to.

Thank you.

Also, I stand corrected. It looks like the first manned Dragon Launch is now set for April. Starliner to follow in June. ( as currently planned).

Also, I forgot Dragons full capacity is 7. So a pilot and 6 passengers for a tourist flight? How much would they be willing to pay to launch, take 10 or 20 (or more) laps and then come down in a re-use capsule. Compare that to Virgin Galactic and Blue Origins sub orbitals. I

Something else I wonder about. With reusables, why build a single stage to Mars vessel or a Lunar-cycler vessel? It does not make sense to me. Build and launch modular and assembled in orbit vessels. With the price dropping, why would this not be the cheaper and safer route.

“So a pilot and 6 passengers for a tourist flight?”

The 1+6 formula is technically true, and I think it would make sense for transporting 6 tourists up to a Bigelow, or other commercial, habitat for a week-to-month stay. But it seems a little cramped for the 20 orbits scenario. After all, what do people want to do in orbit in their free time? 1-stay at the windows and gaze at the beautiful Earth, and 2-float and tumble around and experience microgravity.

For the orbits-only package, might I suggest pilot plus 3 paying passengers?

(not having the funds, what do I know anyway?)

So several people have mentioned Bigelow. But as I understand it, there is currently no date or actual plan to create an orbital habitat yet, correct?

And they will have a hard time overcoming the “space balloon” image. They will have to work to build an image of safety.

sippin_bourbon: Do a search on Behind the Black for “Bigelow” and “beam.” You will learn that Bigelow has already very successfully demonstrated, in space, the safety of its inflatable habitat design.

I had already seen where a module was attached to the ISS.

That is a little different than a stand alone habitat or “space hotel”.

Most of the public does not know its been up there, which is why I think they will still have to work to overcome these concerns.

sippin_bourbon: You do know that Bigelow has also successfully flown, at its own cost, two stand-alone modules in orbit?

Yes, but they were test shots, and expected to come down in the next two years.

mkent wrote: “What is it about the SpaceX cult that requires members to not only love SpaceX but also to hate Boeing and ULA?”

I don’t know about hating Boeing or ULA, but as Robert pointed out: “SpaceX of course is the quintessential example of how to lower costs,” and cost is very important in the space business. Boeing and ULA have not yet announced dramatic reductions in costs, but Blue Origin has. I really do not see why Blue Origin is so often left out of these discussions. Many of us excited about space are excited about both of these companies, and a few more, as they promise low costs for getting to or operating in space, which will lead to far more money being made in space by providing services or goods to we earthlings. The more expensive companies risk being left out of this future bonanza.

I do not understand why those of us who favor efficiency and effectiveness end up being thought of as SpaceX or Musk fanboys or cult members. We root for a number of companies that promise these two qualities, and we are disappointed when some of them leave the business, such as Vector or XCOR.

Leland Jackson wrote: “Regarding the 4 person crew capacity… ISS was designed to have a 7 crew compliment.”

Actually, it was designed for more than seven, but it was built with less capacity. As others have noted, even some of the designed science facilities were not built or launched. We saved a small percentage in terms of dollars, but we are missing out on a lot of science. The result of amortizing the science is that it costs around twice as much as it could have cost. Penny wise but pound foolish.

sippin_bourbon asked: “So several people have mentioned Bigelow. But as I understand it, there is currently no date or actual plan to create an orbital habitat yet, correct? ”

Correct on the launch date, but Bigelow has plans and designs to launch an independent orbital habitat. From March 4th, 2019:

https://www.forbes.com/sites/jonathanocallaghan/2019/03/04/spacexs-crew-dragon-launch-could-make-space-hotels-a-reality/#e19a14ea0dc0

“Last year, the company said it planned to build on this demonstration [BEAM at ISS], and launch the first components of a space hotel in 2021. It is developing a habitat known as the B330, which will have 330 cubic meters of interior space – a third that of the ISS. In 2021, it hopes to launch two of these habitats into space on Atlas V rockets from the United Launch Alliance (ULA). … The B330 is designed to function as a space hotel of sorts, alongside scientific research that will take place on board.”

Atlas V is necessary, because Falcon 9 does not have a fairing that is large enough for the B330. Keep in mind that at least three other companies are planning on their own space Habitats: Axiom Space, Ixion, and Sierra Nevada. Northrup Grumman’s Cygnus cargo ship could become a manned habitat.

Edward,

Well said, and I agree. I root for all of them. Competition!

As for why no one is mentioning Blue Origin, I would only assume because they are still a sub orbital system currently. That is due to change of course.

And thanks for that link on Bigelow.

Why does the crew dragon have to have landing legs if they can just switch out the heat shield every flight?

Propulsive land and just tilt to the side a bit, Big deal. Nothing says the engines have to shut off 10 feet above the ground.

And their is a way to have the legs extend out from the side without going through the heat shield.

And didn’t the shuttle have the same problem with its heat tiles around the landing gear? Never any trouble with that part of the heat shield.

NASA was just making excuses and I bet Space X still has the plans sitting around waiting for NASA to change its mind and say go ahead.

pzatchok wrote: “Why does the crew dragon have to have landing legs if they can just switch out the heat shield every flight?”

Avoid unnecessary shocks on reusable spacecraft or hardware. The heat shield bumping against the landing pad may not matter to the heat shield, because it will be replaced, but the shock can degrade the structure and equipment of the rest of the spacecraft. Landing legs are intended to absorb such shocks and reduce the stresses on the rest of the spacecraft.

“I bet Space X still has the plans sitting around waiting for NASA to change its mind and say go ahead.”

I think that SpaceX’s plan A is to replace the Falcons and Dragons with its BFR series.

One of the problems I see with using large Starships to ferry men and materiel to space stations and space habitats is the large mass of the Starship. It is much easier to perform station keeping and attitude control maneuvers with small spacecraft, such as Dragon, Starliner, Progress, etc., because with the smaller spacecraft docked to these outposts, there is less stress on the docking port and the mass moment of inertia is less affected. This isn’t a show stopper for Starship, just something else that everyone has to think about as they design their hardware, software, and methods.

Edward,

Actually, it was designed for more than seven, but it was built with less capacity. As others have noted, even some of the designed science facilities were not built or launched. We saved a small percentage in terms of dollars, but we are missing out on a lot of science.

Even worse: It wasn’t just science modules that got whacked, but also the Habitation Module, which was supposed to have extensive life support facilities of its own. That right there reduced designed crew size. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Habitation_Module

And then, after that, the Transhab was killed, too (though unlike the Habitation Module, it was never even built).

I think what’s possible at this point, if it happens at all, would be a commercial (probably inflatable) module added on to the station in the coming years, which could support any additional private visitors in terms of intrinsic life support. Otherwise, 7 is going to be the max crew size, short handover periods notwithstanding.

Hello mkent,

I covered this when Robert first reported on this IG report. The gist of it is that the IG report is very misleading, because neither Dragons nor Starliners are sold by the seat, but by the flight.

If I recall correctly way back from contract award, each CCtCap contract has three CLINs: 1) development of the respective commercial crew system, which included an unmanned and a manned test flight 2) from two to six operational flights, and 3) special studies. The optional CLIN 2 flights (all since awarded for each contractor) were, I think, costed out by flight and fiscal year.

Fair point, but in the end, there is no getting around the fact that Boeing bid a higher charge for the operation flight CLIN -for a number of reasons, not least of which is that an Atlas V N22 costs more than double what a new Falcon 9 does. I think, however you calculate it, there is no question that Boeing costs NASA a good deal more than SpaceX does here (though it is possible that some methods might get you under the Soyuz cost).

Mind you, NASA has a good reason for the four-crew / three-cargo split: the USOS life support system can only support a crew of four long-term. However, it can support (I think) up to 13 for short handover periods, so NASA could use either vehicle to ferry a seven-man crew to the ISS for short-term science or maintenance tasks if it chose to do so. Again, not doing so is an operational decision by NASA, not a restriction on either vehicle.

Well…it’s not *impossible* that NASA might choose to take advantage of this particular capability in the future (it might be useful to provide coverage for extensive EVA series, not just research). But adding additional seats means less cargo, and we would need to know more about how highly NASA values that cargo capability.

It could also be, too, that as the ISS core modules ECLLS systems age, NASA might reasonably decide that they want to avoid unduly taxing them with unusually large handover period crew sizes.

I think, again, the best solution here is probably the addition of a large commercial module with its own ECLLS system to support additional (probably private) crew to the station.

I wrote: “One thing that puzzles me is how many people still think that we must choose between going to the Moon and going to Mars. This is thinking that assumes that NASA is going to do these things.”

I’m going to add to this: “it also puzzles me that many people still think that the ISS is going to remain the major means of scientific research through this coming decade.”

I believe that commercial space habitats will very quickly become a major source of research over this coming decade. Not only is there limited amount of science that can be performed on the ISS, but NASA has restrictions that some companies and countries may find onerous.

For instance, data collected by an ISS experiment must be released to the public domain within five years. This is hardly conducive to getting a jump on the competition. It is possible for those performing experiments on commercial habitats to do so under conditions where they need not release their data. What an advantage that would provide.

ISS has produced very few manufactured items, and I do not recall any of them being commercially available. Commercial habitats could provide a manufacturing venue that allows for large amounts of products for Earth consumption, and with Starship taking material to low Earth orbit for somewhere around $2 million to $7 million per hundred tonnes ($9 to $33 per pound or $20 to $70 per kilogram), we could find ourselves with a new bonanza of medications and materials that have so far been unavailable.

Although Richard M is right, there may very likely be a commercial space habitat attached to the ISS in the near future, I think that there will soon be many others in orbit very much independent of ISS, NASA, ESA, JAXA, and Roscosmos and the limitations imposed by them. Just a single Bigelow B330 could double our manned presence in space, and two could triple it. Add to that some more habitats from a couple of the other companies with plans for their own habitats, and we could be assured a permanent continuous presence in space as well as astonishing advancements in science, manufacturing, and space tourism.

The 2010s were exciting because innovation reduced costs of access to space and reduced costs and sizes of satellites, but the 2020s should be even more exciting because of the advancement of commercial space into even more areas and the resulting boon to innovation and entrepreneurship. The upward spiral between commerce, innovation, and entrepreneurs should result in far more prosperity than we have enjoyed from space so far.

Sippin_bourbon asked: “With reusables, why build a single stage to Mars vessel or a Lunar-cycler vessel? It does not make sense to me. Build and launch modular and assembled in orbit vessels. With the price dropping, why would this not be the cheaper and safer route.”

Modular and assembled Lunar-cyclers or Mars-cyclers may be the way to go in the future, but as we saw in the past, we can get exploration sooner by using more brute force methods. Efficiency comes later, as we learn more about what we need and how to do it. When the need arises, some entrepreneur will make it happen at a reasonable price.

Hi Edward,

I think that there will soon be many others in orbit very much independent of ISS, NASA, ESA, JAXA, and Roscosmos and the limitations imposed by them.

This is definitely where the long-term future is headed.

Richard M,

My point is that this is where the short-term future is headed, thanks to the process of privatizing space commerce.

For the past two-thirds of a century, we let space be run by governments, and all we got was what governments wanted. The dreams of the 1940s turned into the ideas of the 1950s, sometimes as seen on Disney, and they turned into the plans of the 1960s, in part as seen with NASA’s Apollo Applications Program. Then Congress and Nixon had their say, and the plans turned into the disappointed expectations of the 1980s, with the failure of the Space Shuttle program (not low cost, not high launch cadence, and it convinced NASA and Congress that reusability was not the future, leading to the non-reusable Constellation and SLS programs).

When We the People got involved in space, privatizing it, we made great things happen, things that government thought were impossible or not worth doing. Peter Diamandis’s X Prize emphasized low cost through reusability, and now one company is reusing a large portion of its launch vehicles and spacecraft, and others are working on reusabilty. We the People got serious about low cost and reusability where governments didn’t.

When we let government run space, all we got was what government wanted. Now that we are starting to run things, we are starting to get what we want, and a large number of space habitats in the coming decade, performing a number of services, is one of the things that we want.

Take seriously Robert’s essays on freedom. Falcon is not the only example of how freedom allows us to innovate and improve on things that seem impossible to improve upon. A favorite cautionary tale of how seemingly beneficial government guidance (interference) can be a terrible idea is:

The French once had a policy that prevented its vintners from modifying their processes, because France had the world’s best wines, and they didn’t want anything to change that standing. In 1976 France held a contest between French and California wines. California didn’t restrict its vintners — they were free to innovate — and California’s wines had become superior to France’s. What a difference policy makes!

The distinction between American governance and the governance of other parts of the world is subtle, but the difference in results is astounding. Some people who comment here have a hard time understanding this, thinking that their own systems are equal or even superior — or at the least not in need of improvement (‘I like it here’ is a paraphrase of one commenter).

Freedom to innovate, competition that drives innovation and efficiency, and profits that reward successful improvements in quality, availability, and price are why free market capitalist countries prosper so much more and so much faster than those that are not as free. With a small policy change to rely more on free market capitalist entrepreneurs rather than government directed suppliers, we are now seeing this rapid increase in prosperity in the space industry. What a difference policy makes!

Commercial space’s Falcon and Electron entries are beginning to beat the pants off the government-directed launchers. I expect that in the next half decade commercial manned spacecraft will beat out government manned spacecraft. I also expect that in the same time frame, commercial space habitats will become the majority customer for those commercial manned spacecraft.