Rocket Lab to reuse previously flown engine on upcoming launch

Rocket Lab engineers, having tested a previously flown Rutherford engine numerous times after recovering it from a launch in May 2022, have now approved that engine for reflight, and are inserting into their Electron rocket assembly line for launch sometime in the third quarter of this year.

The company also revealed that it has now completely abandoned the use of a helicopter in first stage recovery, and will instead pick up all first stages after they have splashed down in the ocean.

Extensive analysis of returned stages shows that Electron withstands an ocean splashdown and engineers expect future complete stages to pass qualification and acceptance testing for re-flight with minimal refurbishment. As a result, Rocket Lab is moving forward with marine operations as the primary method of recovering Electron for re-flight. This is expected to take the number of Electron missions suitable for recovery from around 50% to between 60-70% of missions due to fewer weather constraints faced by marine recovery vs mid-air capture, while also reducing costs associated with helicopter operations.

Rocket Lab will assess the opportunities for flying a complete pre-flown first stage booster following the launch of the pre-flown Rutherford engine in the third quarter this year.

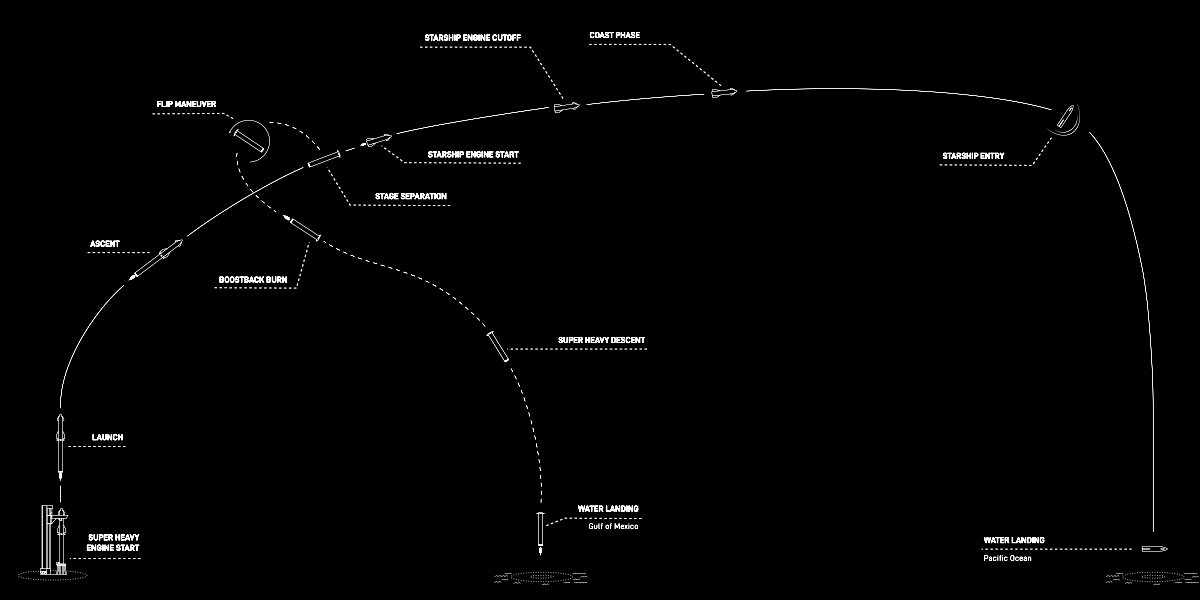

Rocket Lab is presently the only operational American company besides SpaceX that is aggressively pursuing reuse of its rocket. ULA says it wishes to recover and reuse the engines of its still-unflown Vulcan rocket, but development of this concept has been very slow. Many other new companies claim their rockets will be reusable, but none has yet even launched.

Rocket Lab engineers, having tested a previously flown Rutherford engine numerous times after recovering it from a launch in May 2022, have now approved that engine for reflight, and are inserting into their Electron rocket assembly line for launch sometime in the third quarter of this year.

The company also revealed that it has now completely abandoned the use of a helicopter in first stage recovery, and will instead pick up all first stages after they have splashed down in the ocean.

Extensive analysis of returned stages shows that Electron withstands an ocean splashdown and engineers expect future complete stages to pass qualification and acceptance testing for re-flight with minimal refurbishment. As a result, Rocket Lab is moving forward with marine operations as the primary method of recovering Electron for re-flight. This is expected to take the number of Electron missions suitable for recovery from around 50% to between 60-70% of missions due to fewer weather constraints faced by marine recovery vs mid-air capture, while also reducing costs associated with helicopter operations.

Rocket Lab will assess the opportunities for flying a complete pre-flown first stage booster following the launch of the pre-flown Rutherford engine in the third quarter this year.

Rocket Lab is presently the only operational American company besides SpaceX that is aggressively pursuing reuse of its rocket. ULA says it wishes to recover and reuse the engines of its still-unflown Vulcan rocket, but development of this concept has been very slow. Many other new companies claim their rockets will be reusable, but none has yet even launched.