Changes on the surface of Comet 67P/C-G

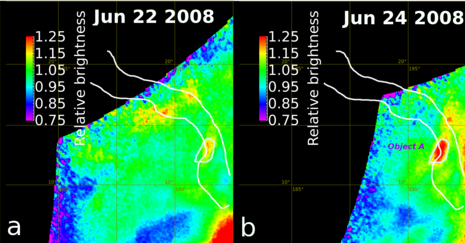

In a science paper now accepted for publication, the Rosetta science team have described changes that have occurred on the surface of Comet 67P/C-G from May through July of this year as the comet moved closer to the Sun and activity increased.

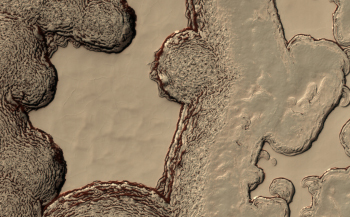

The changes were seen in a smooth area dubbed Imhotep.

First evidence for a new, roughly round feature in Imhotep was seen in an image taken with Rosetta’s OSIRIS narrow-angle camera on 3 June. Subsequent images later in June showed this feature growing in size, and being joined by a second round feature. By 2 July, they had reached diameters of roughly 220 m and 140 m, respectively, and another new feature began to appear.

By the time of the last image used in this study, taken on 11 July, these three features had merged into one larger region and yet another two features had appeared.

Be sure to click on the link to see the images. The changes look like a surface layer is slowing evaporating away.

In a science paper now accepted for publication, the Rosetta science team have described changes that have occurred on the surface of Comet 67P/C-G from May through July of this year as the comet moved closer to the Sun and activity increased.

The changes were seen in a smooth area dubbed Imhotep.

First evidence for a new, roughly round feature in Imhotep was seen in an image taken with Rosetta’s OSIRIS narrow-angle camera on 3 June. Subsequent images later in June showed this feature growing in size, and being joined by a second round feature. By 2 July, they had reached diameters of roughly 220 m and 140 m, respectively, and another new feature began to appear.

By the time of the last image used in this study, taken on 11 July, these three features had merged into one larger region and yet another two features had appeared.

Be sure to click on the link to see the images. The changes look like a surface layer is slowing evaporating away.