Summary: Curiosity drives down off of Vera Rubin Ridge to do drilling in lower Murray Formation geology unit, while Opportunity continues to puzzle over the formation process that created Perseverance Valley in the rim of Endeavour Crater.

For a list of past updates beginning in July 2016, see my February 8, 2018 update.

Curiosity

For the overall context of Curiosity’s travels, see Pinpointing Curiosity’s location in Gale Crater.

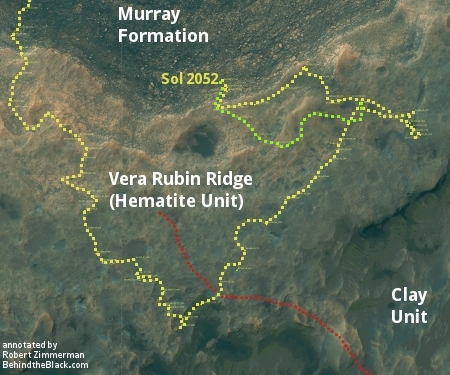

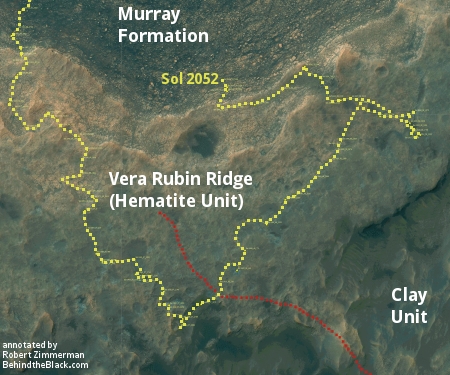

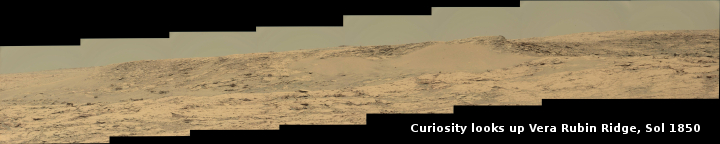

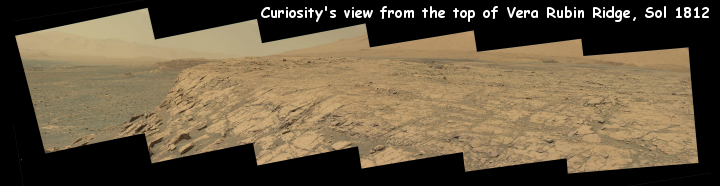

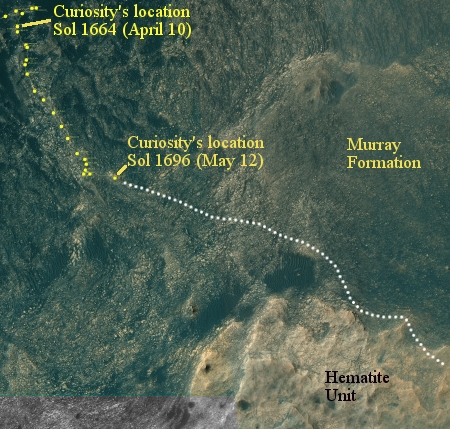

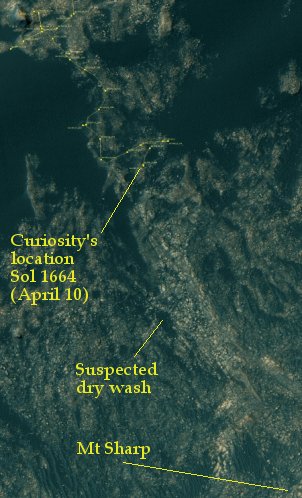

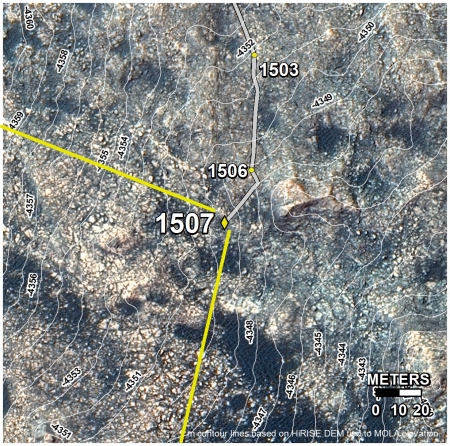

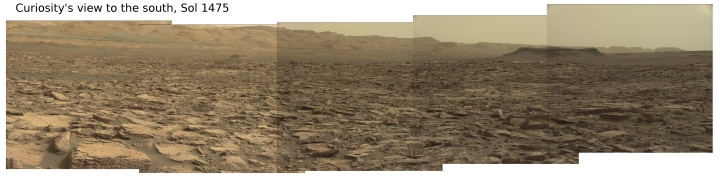

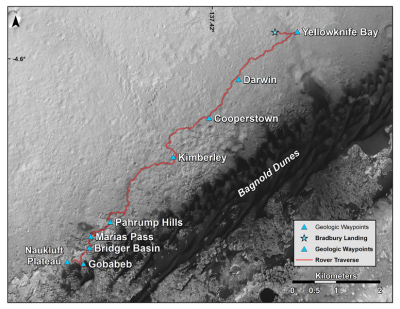

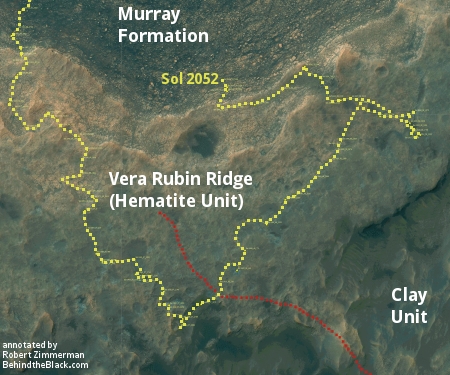

Since my April 27, 2018 update, Curiosity has continued its downward trek off of Vera Rubin Ridge back in the direction from which it came. The annotated traverse map to the right, cropped and taken from the rover’s most recent full traverse map, shows the rover’s recent circuitous route with the yellow dotted line. The red dotted line shows the originally planned route off of Vera Rubin Ridge, which they have presently bypassed.

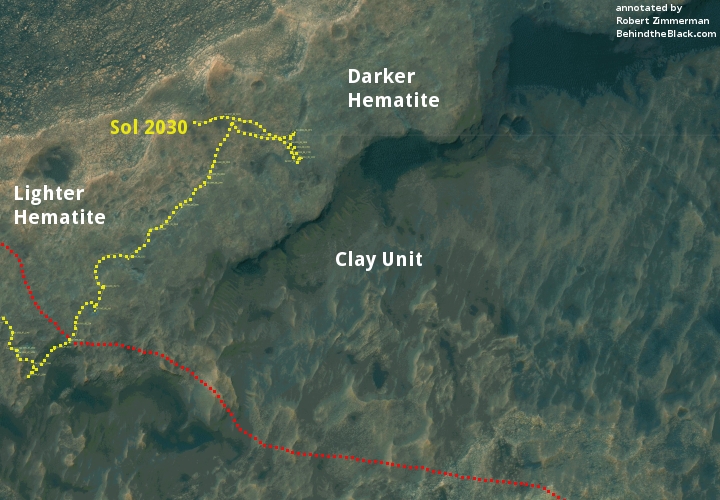

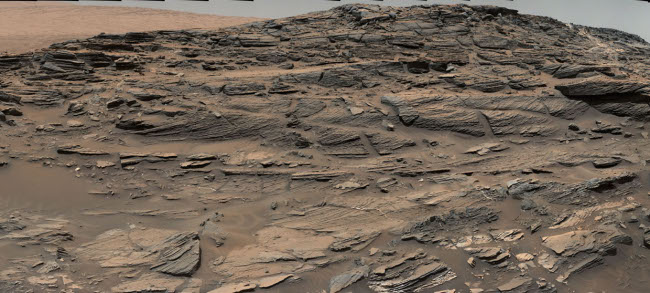

It appears they have had several reasons for returning to the Murray Formation below the Hematite Unit on Vera Rubin Ridge. First, it appears they wanted to get more data about the geological layers just below the Hematite Unit, including the layer immediately below, dubbed the Blunts Point member.

While this is certainly their main goal, I also suspect that they wanted to find a good and relatively easy drilling candidate to test their new drill technique. The last two times they tested this new technique, which bypasses the drill’s stuck feed mechanism by having the robot arm itself push the drill bit against the rock, the drilling did not succeed. It appeared the force applied by the robot arm to push the drill into the rock was not sufficient. The rock was too hard.

In these first attempts, however, they only used the drill’s rotation to drill, thus reducing the stress on the robot arm. The rotation however was insufficient. Thus, they decided with the next drill attempt to add the drill’s “percussion” capability, where it would not only rotate but also repeatedly pound up and down, the way a standard hammer drill works on Earth.

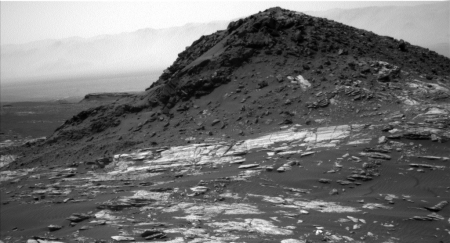

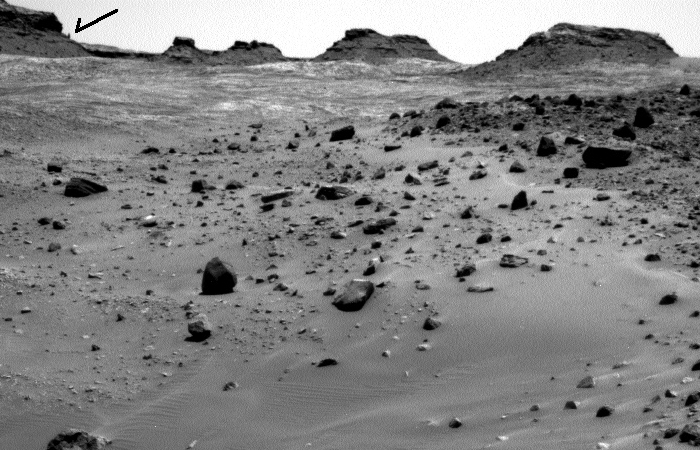

I suspect that they are proceeding carefully with this because this new technique places stress the operation of the robot arm, something they absolutely do not want to lose. By leaving Vera Rubin Ridge they return to the more delicate and softer materials already explored in the Murray Formation. This is very clear in the photo below, cropped from the original to post here, showing the boulder they have chosen to drill into, dubbed “Duluth,” with the successful drill hole to the right.

» Read more