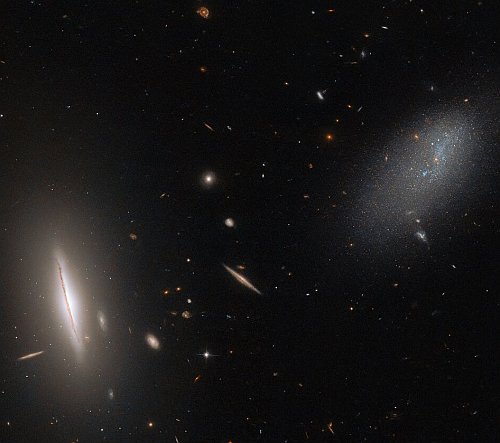

Webb finds another galaxy in early universe that should not exist

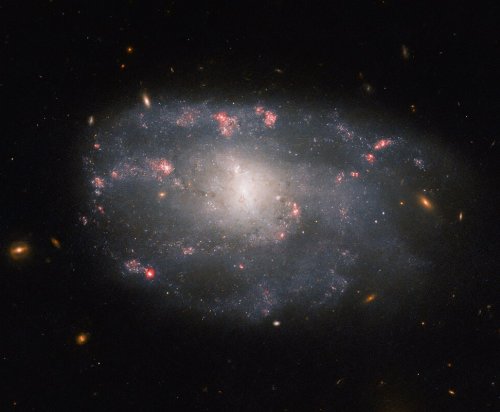

The uncertainty of science: Scientists using the Webb Space Telescope have identified another galaxy about 12 billion light years away and only about 1.7 billion years after the theorized Big Bang that is too rich in chemicals as well as too active in star formation to have had time to form.

SPT0418-SE is believed to have already hosted multiple generations of stars, despite its young age. Both of the galaxies have a mature metallicity — or large amounts of elements like carbon, oxygen and nitrogen that are heavier than hydrogen and helium — which is similar to the sun. However, our sun is 4.5 billion years old and inherited most of its metals from previous generations of stars that were eight billion years old, the researchers said.

In other words, this galaxy somehow obtained complex elements in only 1.7 billion years that in our galaxy took twelve billion years, something that defies all theories of galactic and stellar evolution. Either the Big Bang did not happen when it did, or all theories about the growth and development of galaxies are wrong.

One could reasonably argue that this particular observation might be mistaken, except that it is not the only one from Webb that shows similar data. Webb’s infrared data is challenging the fundamentals of all cosmology, developed by theorists over the past half century.

The uncertainty of science: Scientists using the Webb Space Telescope have identified another galaxy about 12 billion light years away and only about 1.7 billion years after the theorized Big Bang that is too rich in chemicals as well as too active in star formation to have had time to form.

SPT0418-SE is believed to have already hosted multiple generations of stars, despite its young age. Both of the galaxies have a mature metallicity — or large amounts of elements like carbon, oxygen and nitrogen that are heavier than hydrogen and helium — which is similar to the sun. However, our sun is 4.5 billion years old and inherited most of its metals from previous generations of stars that were eight billion years old, the researchers said.

In other words, this galaxy somehow obtained complex elements in only 1.7 billion years that in our galaxy took twelve billion years, something that defies all theories of galactic and stellar evolution. Either the Big Bang did not happen when it did, or all theories about the growth and development of galaxies are wrong.

One could reasonably argue that this particular observation might be mistaken, except that it is not the only one from Webb that shows similar data. Webb’s infrared data is challenging the fundamentals of all cosmology, developed by theorists over the past half century.