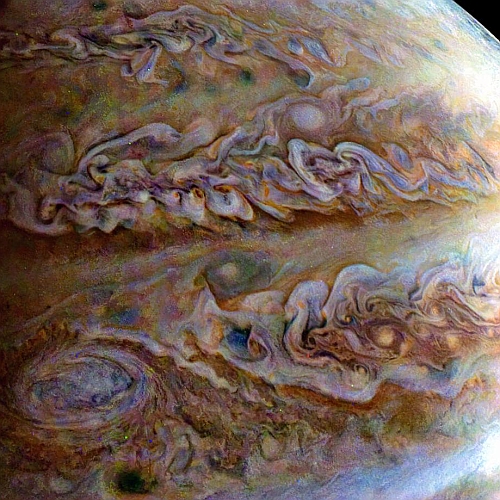

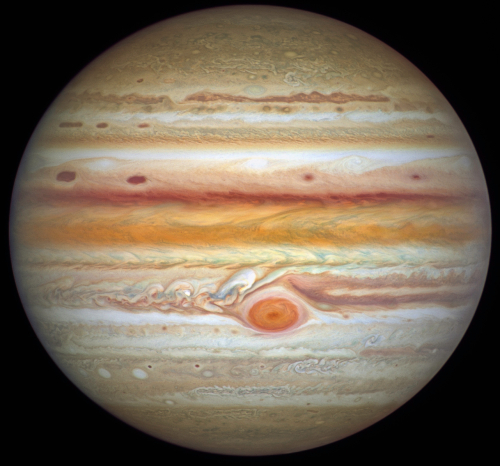

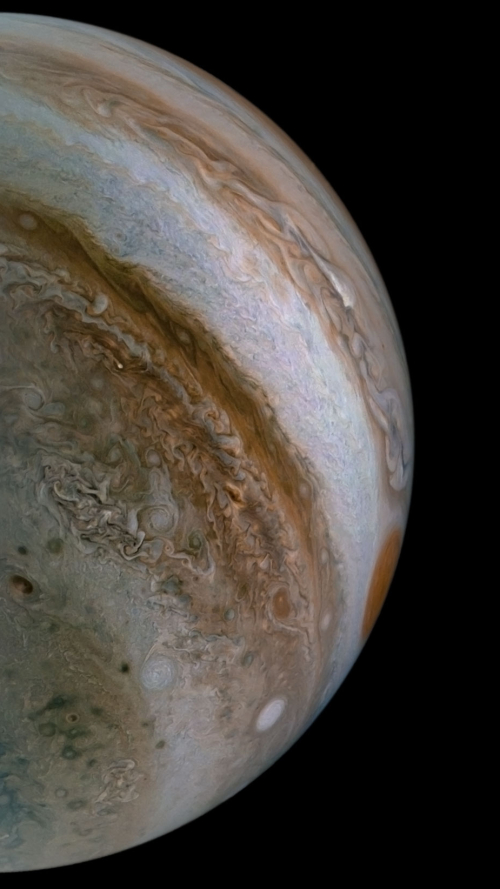

Storm fronts on Jupiter

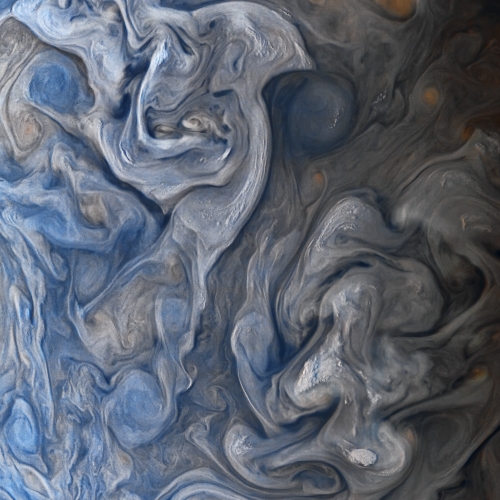

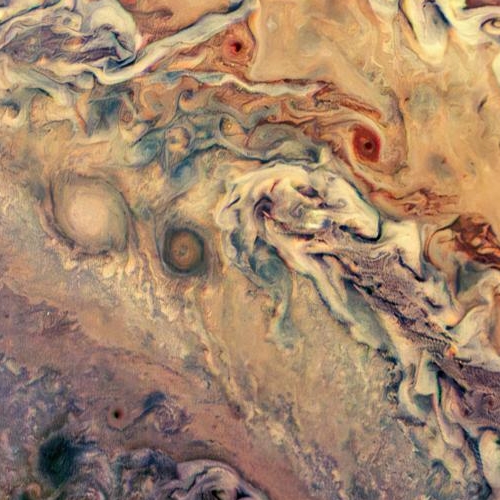

Cool image time! The picture to the right, cropped and reduced to post here, was processed by citizen scientist Thomas Thomopoulos from a raw image taken by the Jupiter orbiter Juno on August 17, 2022.

The orbiter was 18,354 miles above the cloud tops when the image was snapped. It shows a stormy cloud band in the southern hemisphere.

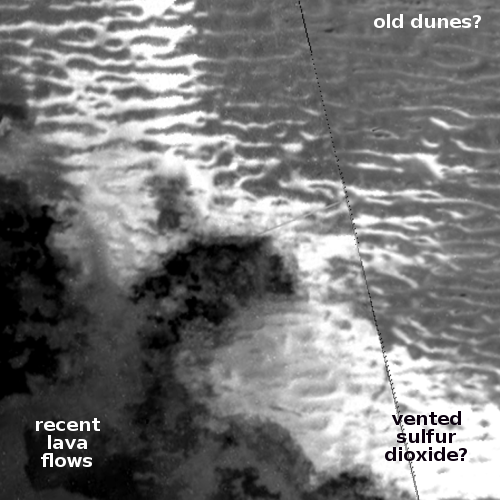

You can get a sense of the processing that Thomospoulos did by comparing this image with the raw photo. The original has almost no contrast, either in color or in contrast. By enhancing both Thomospoulos makes the violent nature of these large storms, thousands of miles in size, quite visible.

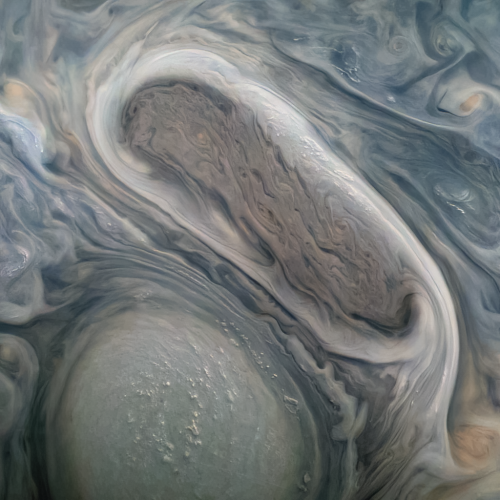

Cool image time! The picture to the right, cropped and reduced to post here, was processed by citizen scientist Thomas Thomopoulos from a raw image taken by the Jupiter orbiter Juno on August 17, 2022.

The orbiter was 18,354 miles above the cloud tops when the image was snapped. It shows a stormy cloud band in the southern hemisphere.

You can get a sense of the processing that Thomospoulos did by comparing this image with the raw photo. The original has almost no contrast, either in color or in contrast. By enhancing both Thomospoulos makes the violent nature of these large storms, thousands of miles in size, quite visible.