Drilling success for Curiosity

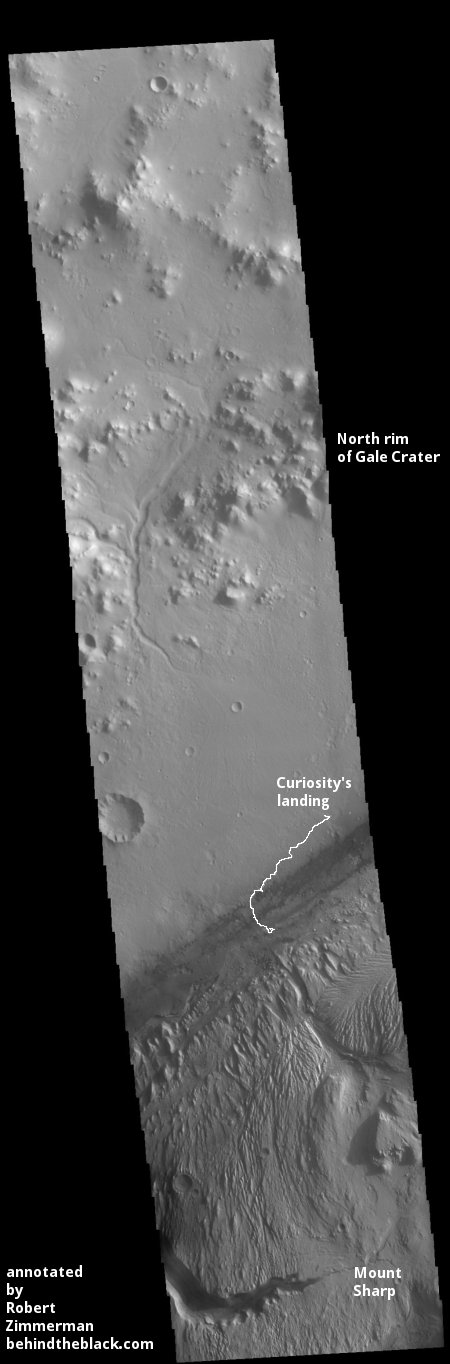

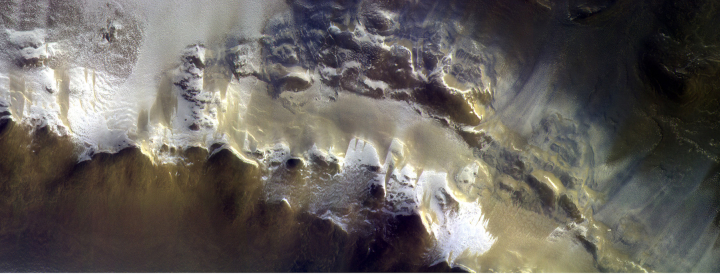

For the first time in more than a year, Curiosity has successfully used its drill to obtain a sample from beneath the surface of Mars.

Curiosity tested percussive drilling this past weekend, penetrating about 2 inches (50 millimeters) into a target called “Duluth.”

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, has been testing this drilling technique since a mechanical problem took Curiosity’s drill offline in December of 2016. This technique, called Feed Extended Drilling, keeps the drill’s bit extended out past two stabilizer posts that were originally used to steady the drill against Martian rocks. It lets Curiosity drill using the force of its robotic arm, a little more like the way a human would drill into a wall at home.

I plan to post a rover update either today or tomorrow, with more details about this success. Stay tuned!

For the first time in more than a year, Curiosity has successfully used its drill to obtain a sample from beneath the surface of Mars.

Curiosity tested percussive drilling this past weekend, penetrating about 2 inches (50 millimeters) into a target called “Duluth.”

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, has been testing this drilling technique since a mechanical problem took Curiosity’s drill offline in December of 2016. This technique, called Feed Extended Drilling, keeps the drill’s bit extended out past two stabilizer posts that were originally used to steady the drill against Martian rocks. It lets Curiosity drill using the force of its robotic arm, a little more like the way a human would drill into a wall at home.

I plan to post a rover update either today or tomorrow, with more details about this success. Stay tuned!