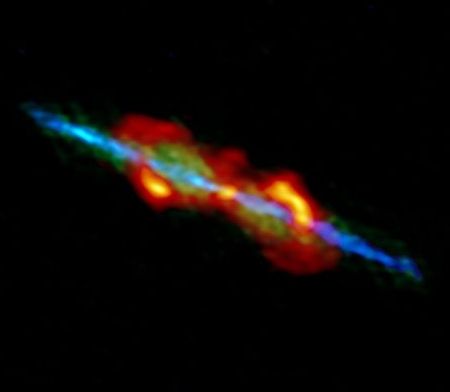

Astronomers more precisely estimate the diameter of neutron stars

Using several different techniques, astronomers now estimate that the typical neutron star will have a diameter of 11 kilometers, or about 7 miles.

What is significant about this new estimate is that if that neutron star happens to be orbiting a black hole and get pulled into it, it will be swallowed whole instead of being ripped apart.

Their results, which appeared in Nature Astronomy today, are more stringent by a factor of two than previous limits and show that a typical neutron star has a radius close to 11 kilometers. They also find that neutron stars merging with black holes are in most cases likely to be swallowed whole, unless the black hole is small and/or rapidly rotating. This means that while such mergers might be observable as gravitational-wave sources, they would be invisible in the electromagnetic spectrum.

In other words, such cataclysmic events would be largely invisible to observers.

Using several different techniques, astronomers now estimate that the typical neutron star will have a diameter of 11 kilometers, or about 7 miles.

What is significant about this new estimate is that if that neutron star happens to be orbiting a black hole and get pulled into it, it will be swallowed whole instead of being ripped apart.

Their results, which appeared in Nature Astronomy today, are more stringent by a factor of two than previous limits and show that a typical neutron star has a radius close to 11 kilometers. They also find that neutron stars merging with black holes are in most cases likely to be swallowed whole, unless the black hole is small and/or rapidly rotating. This means that while such mergers might be observable as gravitational-wave sources, they would be invisible in the electromagnetic spectrum.

In other words, such cataclysmic events would be largely invisible to observers.