One instrument on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter ends its mission

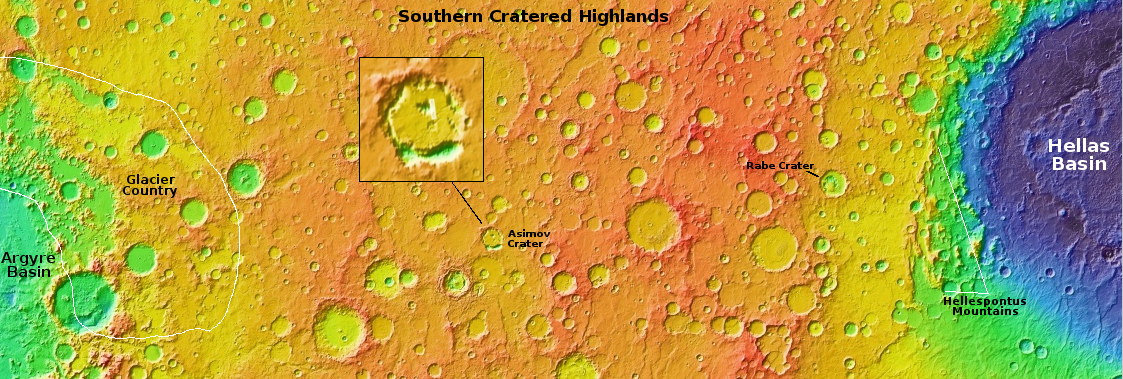

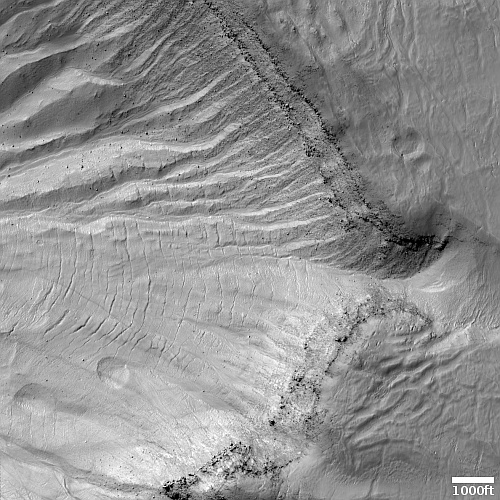

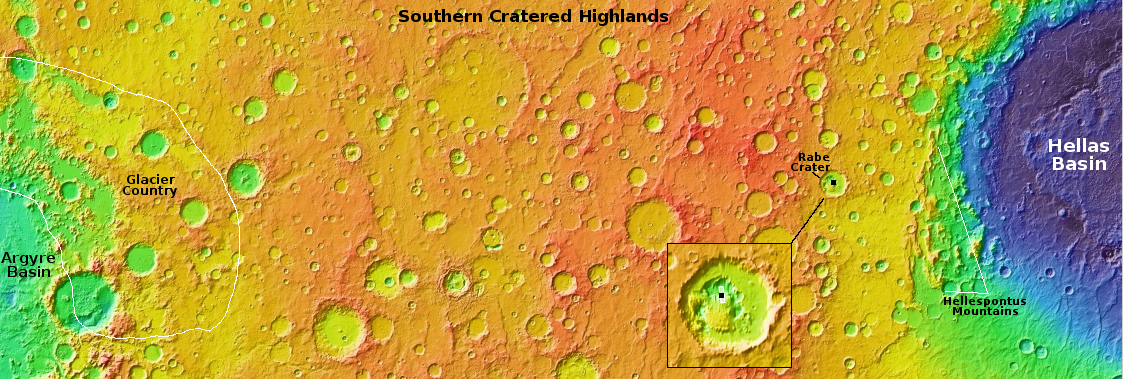

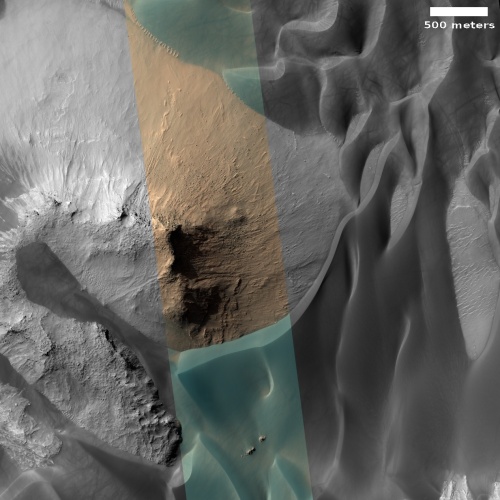

Because Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter’s (MRO) CRISM instrument needed to be cooled to low temperatures to use infrared wavelengths for detecting underground minerals and ice on Mars, and the cryocoolers have run out of coolant, the science team has shut the instrument down.

In order to study infrared light, which is radiated by warm objects and is invisible to the human eye, CRISM relied on cryocoolers to isolate one of its spectrometers from the warmth of the spacecraft. Three cryocoolers were used in succession, and the last completed its lifecycle in 2017.

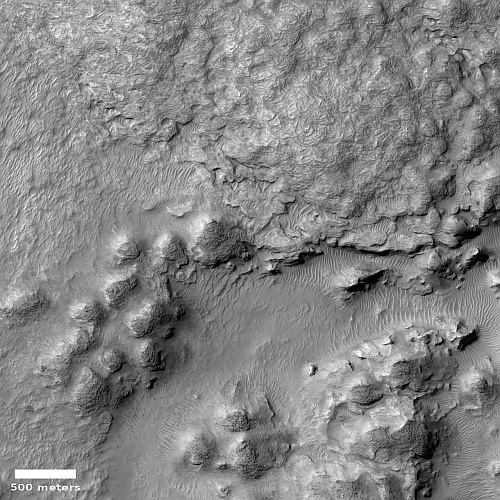

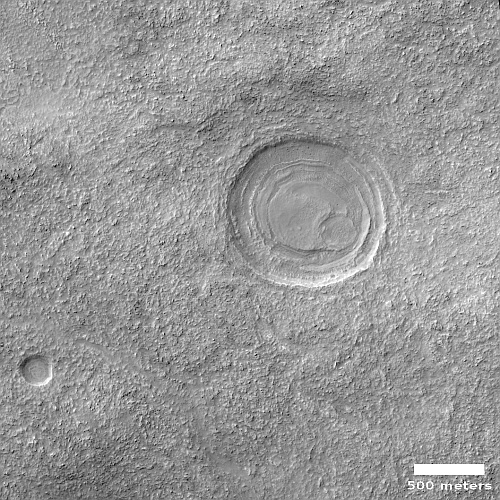

All the remaining instruments on MRO, including its two cameras, continue to operate nominally.

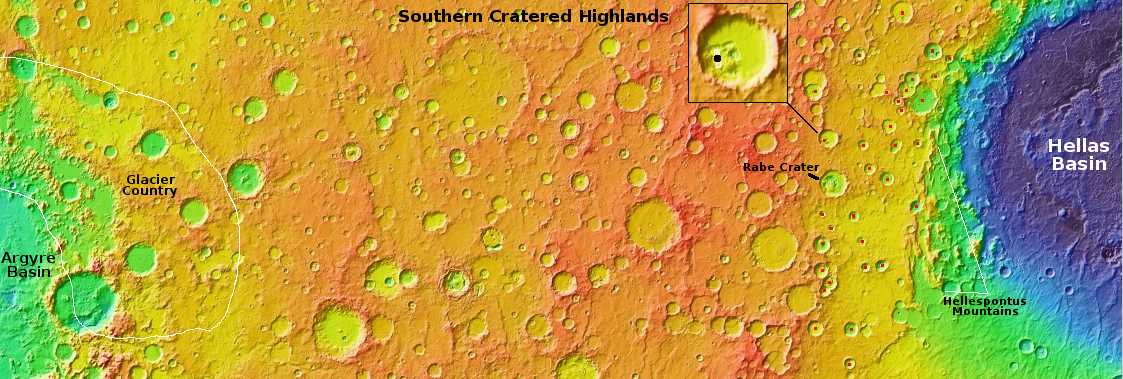

In its final task, CRISM produced a global map showing water related minerals on Mars, released last year, and a global map showing iron deposits, to be released later this year.

Because Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter’s (MRO) CRISM instrument needed to be cooled to low temperatures to use infrared wavelengths for detecting underground minerals and ice on Mars, and the cryocoolers have run out of coolant, the science team has shut the instrument down.

In order to study infrared light, which is radiated by warm objects and is invisible to the human eye, CRISM relied on cryocoolers to isolate one of its spectrometers from the warmth of the spacecraft. Three cryocoolers were used in succession, and the last completed its lifecycle in 2017.

All the remaining instruments on MRO, including its two cameras, continue to operate nominally.

In its final task, CRISM produced a global map showing water related minerals on Mars, released last year, and a global map showing iron deposits, to be released later this year.