Mars’ fast moving gigantic lava floods

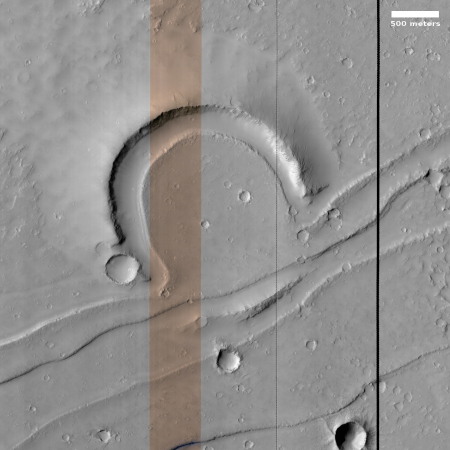

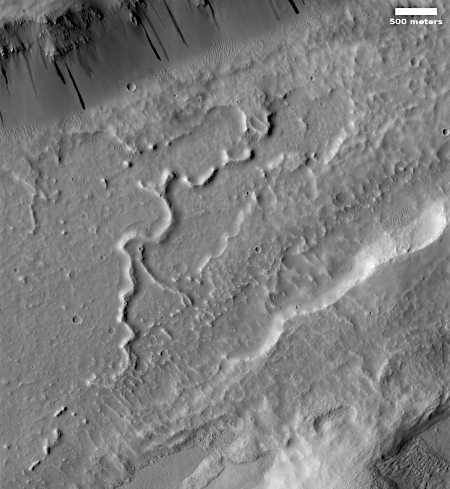

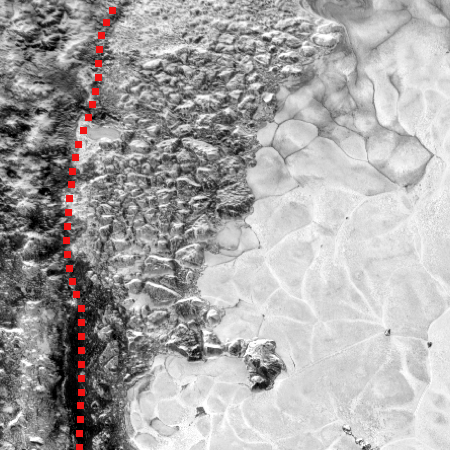

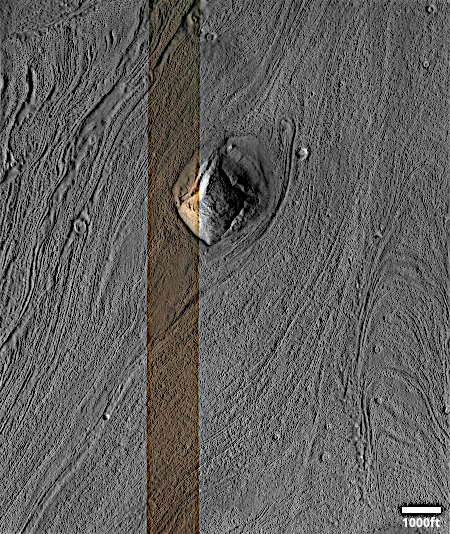

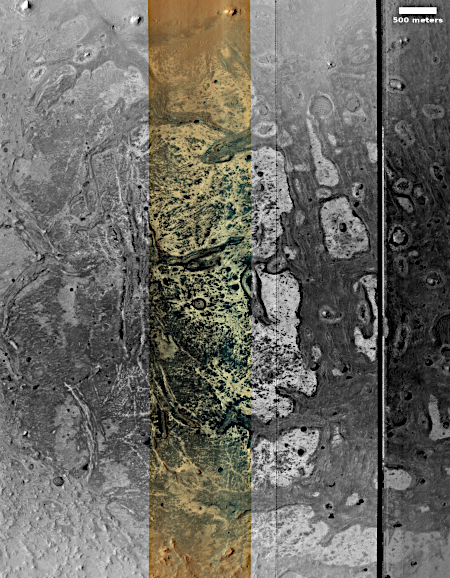

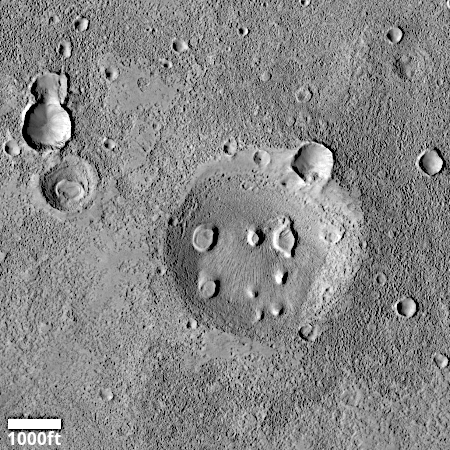

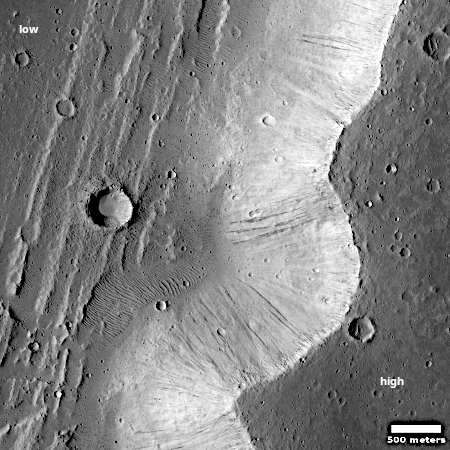

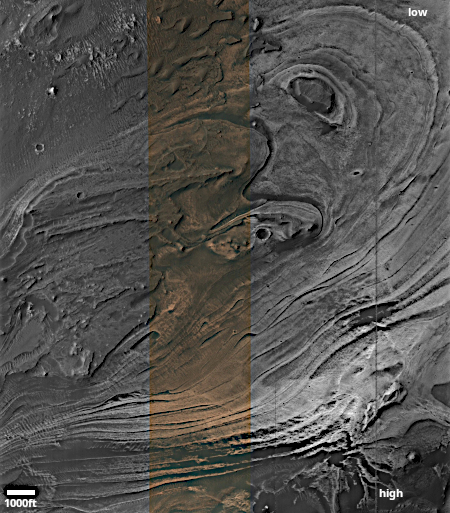

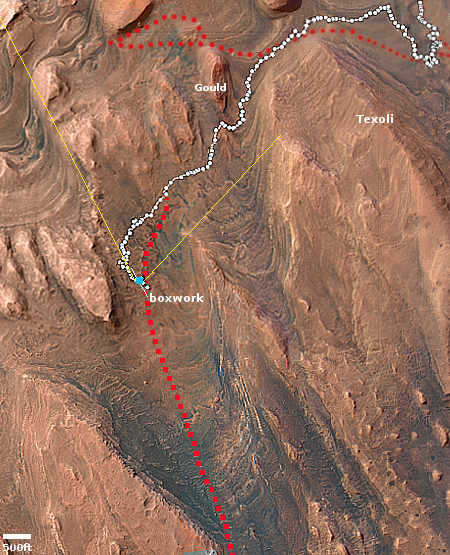

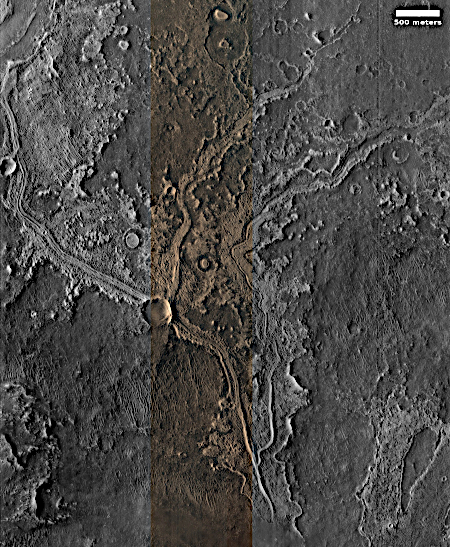

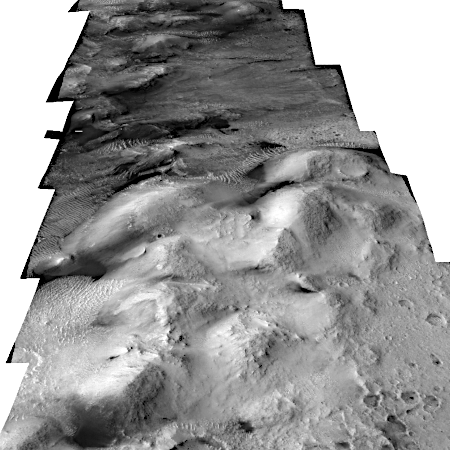

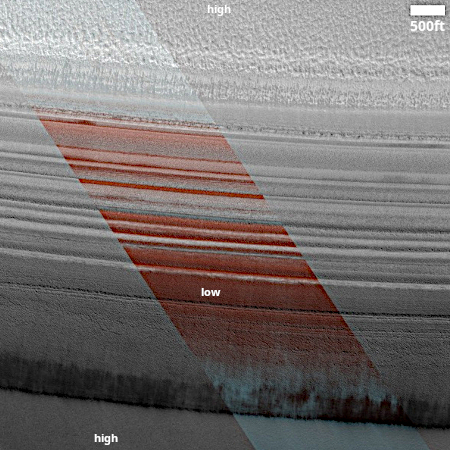

Cool image time! The picture to the right, rotated, cropped, and reduced to post here, was taken on December 12, 2025 by the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO).

The science team labels this a “crater interrupted by flow.” And what a flow! This unnamed 1.4-mile wide crater was not only filled and partly buried by the flow, that flow was so strong it cut through the crater’s rim at two points, refusing to let that rim block it in any way.

The flow in this case is lava, coming down from the Tharsis Bulge where four of Mars’ biggest volcanoes arose. And that flow was quite vast, as the nearest of those volcanoes, Arsia Mons, is almost 800 miles away. Because of Mars’ relative light gravity, about 39% that of Earth’s, lava on Mars can flow across large distances in a very short time. It might have only taken a few weeks for that flow to cover that 800 miles.

» Read more

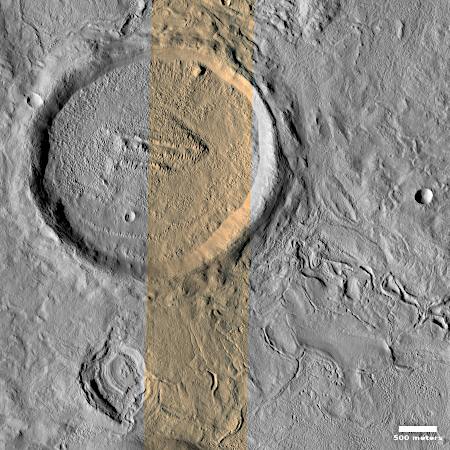

Cool image time! The picture to the right, rotated, cropped, and reduced to post here, was taken on December 12, 2025 by the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO).

The science team labels this a “crater interrupted by flow.” And what a flow! This unnamed 1.4-mile wide crater was not only filled and partly buried by the flow, that flow was so strong it cut through the crater’s rim at two points, refusing to let that rim block it in any way.

The flow in this case is lava, coming down from the Tharsis Bulge where four of Mars’ biggest volcanoes arose. And that flow was quite vast, as the nearest of those volcanoes, Arsia Mons, is almost 800 miles away. Because of Mars’ relative light gravity, about 39% that of Earth’s, lava on Mars can flow across large distances in a very short time. It might have only taken a few weeks for that flow to cover that 800 miles.

» Read more