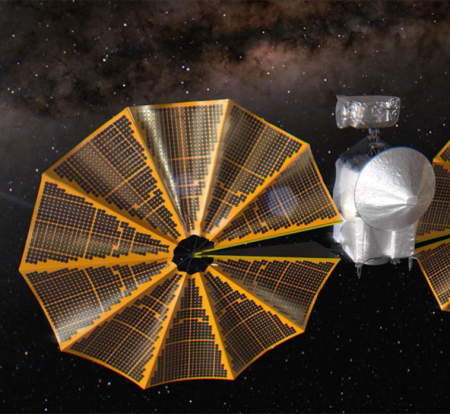

An eccentric debris disk circling a nearby star

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, astronomers have discovered that the debris disk surrounding a star about 60 light years away, discovered in 2006 by the Hubble Space Telescope, is not circular, but instead forms an eccentric ring about the star.

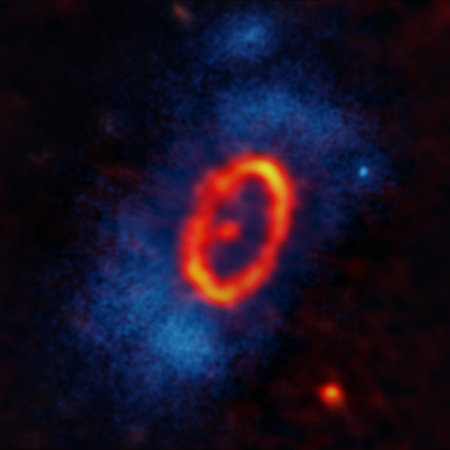

The photo to the right combines the Hubble data (the blue background) and the ALMA data (the orange-yellow ring). The star is the bright spot in the ring, not in its center but at one of the ellipse’s two foci.

This level of eccentricity, MacGregor said, makes HD 53143 the most eccentric debris disk observed to date, being twice as eccentric as the Fomalhaut debris disk, which MacGregor fully imaged at millimeter wavelengths using ALMA in 2017. “So far, we have not found many disks with a significant eccentricity. In general, we don’t expect disks to be very eccentric unless something, like a planet, is sculpting them and forcing them to be eccentric. Without that force, orbits tend to circularize, like what we see in our own Solar System.”

In other words, there must be at least one hidden planet, maybe more, orbiting the star, its gravity forcing the disk into this shape.

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, astronomers have discovered that the debris disk surrounding a star about 60 light years away, discovered in 2006 by the Hubble Space Telescope, is not circular, but instead forms an eccentric ring about the star.

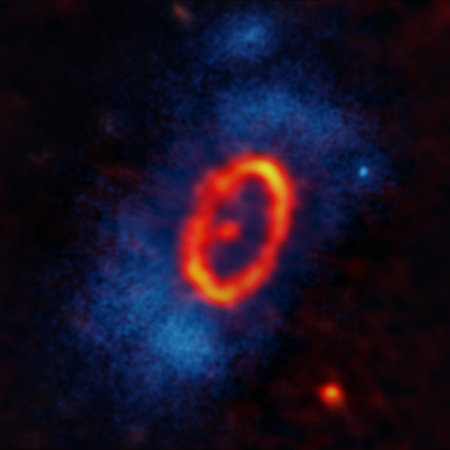

The photo to the right combines the Hubble data (the blue background) and the ALMA data (the orange-yellow ring). The star is the bright spot in the ring, not in its center but at one of the ellipse’s two foci.

This level of eccentricity, MacGregor said, makes HD 53143 the most eccentric debris disk observed to date, being twice as eccentric as the Fomalhaut debris disk, which MacGregor fully imaged at millimeter wavelengths using ALMA in 2017. “So far, we have not found many disks with a significant eccentricity. In general, we don’t expect disks to be very eccentric unless something, like a planet, is sculpting them and forcing them to be eccentric. Without that force, orbits tend to circularize, like what we see in our own Solar System.”

In other words, there must be at least one hidden planet, maybe more, orbiting the star, its gravity forcing the disk into this shape.