Astronomers detect chemicals on exoplanet that on Earth come from life

The uncertainty of science: Using the Webb Space Telescope, astronomers have detected two different molecules that on Earth are only linked with biology in the atmosphere of an exoplanet orbiting a red dwarf star within its habitable zone.

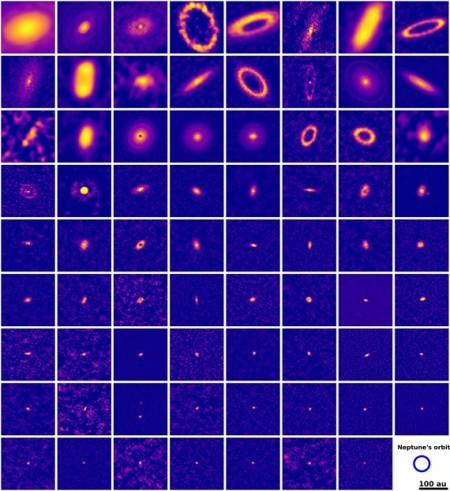

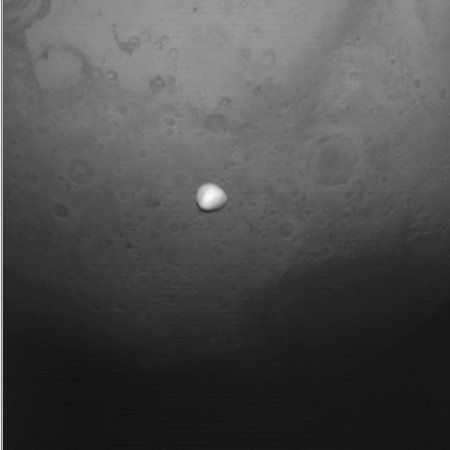

Earlier observations of K2-18b — which is 8.6 times as massive and 2.6 times as large as Earth, and lies 124 light years away in the constellation of Leo — identified methane and carbon dioxide in its atmosphere. This was the first time that carbon-based molecules were discovered in the atmosphere of an exoplanet in the habitable zone. Those results were consistent with predictions for a ‘Hycean’ planet: a habitable ocean-covered world underneath a hydrogen-rich atmosphere.

However, another, weaker signal hinted at the possibility of something else happening on K2-18b. “We didn’t know for sure whether the signal we saw last time was due to DMS, but just the hint of it was exciting enough for us to have another look with JWST using a different instrument,” said Professor Nikku Madhusudhan from Cambridge’s Institute of Astronomy, who led the research.

…The earlier, tentative, inference of DMS was made using JWST’s NIRISS (Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph) and NIRSpec (Near-Infrared Spectrograph) instruments, which together cover the near-infrared (0.8-5 micron) range of wavelengths. The new, independent observation [of dimethyl sulfide (DMS) and/or dimethyl disulfide (DMDS] used JWST’s MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument) in the mid-infrared (6-12 micron) range.

This data is not yet proof of biology. For example, the concentrations of these molecules in K2-18b’s atmosphere is thousands of times greater than on Earth. It is just as likely that numerous as yet unknown non-biological chemical processes in this alien environment have produced these chemicals. The scientists however are encouraged because the theories about ocean life on this kind of habitable ocean-covered superearth had predicted this high concentration of these chemicals.

At the same time, they readily admit there are many uncertainties in their data. They have asked for another 16 to 24 hours of observation time on Webb — a very large chunk rarely given out to one research group — to reduce these uncertainties.

You can read the peer-reviewed paper here [pdf].

The uncertainty of science: Using the Webb Space Telescope, astronomers have detected two different molecules that on Earth are only linked with biology in the atmosphere of an exoplanet orbiting a red dwarf star within its habitable zone.

Earlier observations of K2-18b — which is 8.6 times as massive and 2.6 times as large as Earth, and lies 124 light years away in the constellation of Leo — identified methane and carbon dioxide in its atmosphere. This was the first time that carbon-based molecules were discovered in the atmosphere of an exoplanet in the habitable zone. Those results were consistent with predictions for a ‘Hycean’ planet: a habitable ocean-covered world underneath a hydrogen-rich atmosphere.

However, another, weaker signal hinted at the possibility of something else happening on K2-18b. “We didn’t know for sure whether the signal we saw last time was due to DMS, but just the hint of it was exciting enough for us to have another look with JWST using a different instrument,” said Professor Nikku Madhusudhan from Cambridge’s Institute of Astronomy, who led the research.

…The earlier, tentative, inference of DMS was made using JWST’s NIRISS (Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph) and NIRSpec (Near-Infrared Spectrograph) instruments, which together cover the near-infrared (0.8-5 micron) range of wavelengths. The new, independent observation [of dimethyl sulfide (DMS) and/or dimethyl disulfide (DMDS] used JWST’s MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument) in the mid-infrared (6-12 micron) range.

This data is not yet proof of biology. For example, the concentrations of these molecules in K2-18b’s atmosphere is thousands of times greater than on Earth. It is just as likely that numerous as yet unknown non-biological chemical processes in this alien environment have produced these chemicals. The scientists however are encouraged because the theories about ocean life on this kind of habitable ocean-covered superearth had predicted this high concentration of these chemicals.

At the same time, they readily admit there are many uncertainties in their data. They have asked for another 16 to 24 hours of observation time on Webb — a very large chunk rarely given out to one research group — to reduce these uncertainties.

You can read the peer-reviewed paper here [pdf].