Link here. This is a detailed article describing the meeting in March where the solar science community gathered to formulate its prediction for the next solar cycle.

What stands out about the meeting is the outright uncertainty the scientists have about any prediction they might make. It is very clear that they recognize that all their predictions, both in the past and now, are not based on any actual understanding the Sun’s magnetic processes that form sunspots and cause its activity cycles, but on superficial statistics and using the past visual behavior of the Sun to predict its future behavior.

“There’s not very much physics involved,” concedes panelist Rachel Howe of the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom, who has been tasked with reviewing the mishmash of statistical models. “There’s not very much statistical sophistication either.”

Panelist Andrés Muñoz-Jaramillo of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder agrees with Howe. “There is no connection whatsoever to solar physics,” he says in frustration. McIntosh, who by now has walked downstairs from his office and appears in the doorway, is blunter. “You’re trying to get rid of numerology?” he says, smirking.

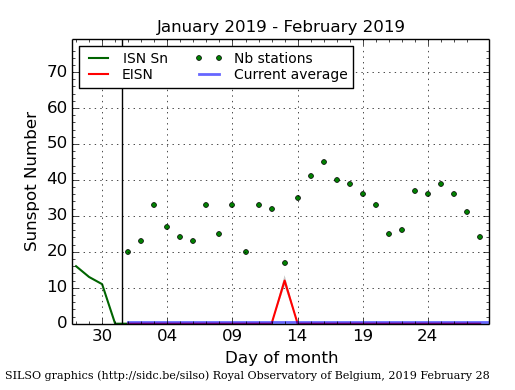

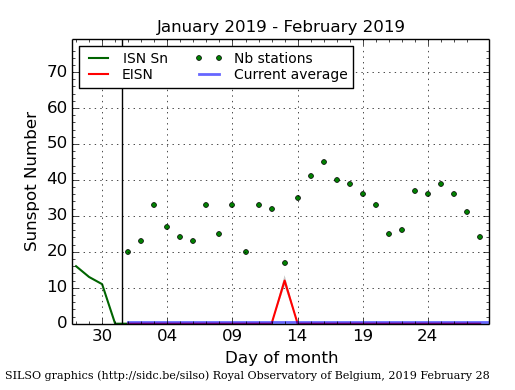

The result, as I repeatedly note in my monthly sunspot updates, is that the last prediction failed, and that there is now great disagreement among these scientists about what will happen in the upcoming cycle.

[They] dutifully tabulate the estimates, and come up with a peak sunspot range: 95 to 130. This spells a weak cycle, but not notably so, and it’s marginally stronger than the past cycle. [They do] the same with the votes for the timing of minimum. The consensus is that it will come sometime between July 2019 and September 2020. Maximum will follow sometime between 2023 and 2026.

The range of predictions here is so great that essentially it shows that there really is no consensus on what will happen, which also explains why the prediction has still not been added to NOAA’s monthly sunspot graph. For past cycles the Sun’s behavior was relatively consistent and reliable, making such statistical and superficial predictions reasonably successful.

The situation now is more elusive. For the past dozen or so years the Sun has not been behaving in a consistent or reliable manner. Thus, the next cycle might be stronger, it could be weak, or we might be heading into a grand minimum, with no sunspots for many decades. These scientists simply do not know, and without a proper understanding of the Sun’s dynamo and magnetic field, they cannot make a sunspot prediction that anyone can trust.

And so they wait and watch, as we all. The Sun will do what the Sun wants to do, and only from this we will maybe be able to finally begin to glean an understanding of why.