A 10-mile-long avalanche on Mars

Click for original image.

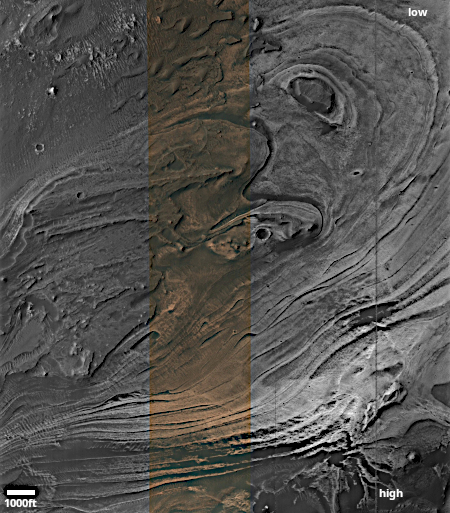

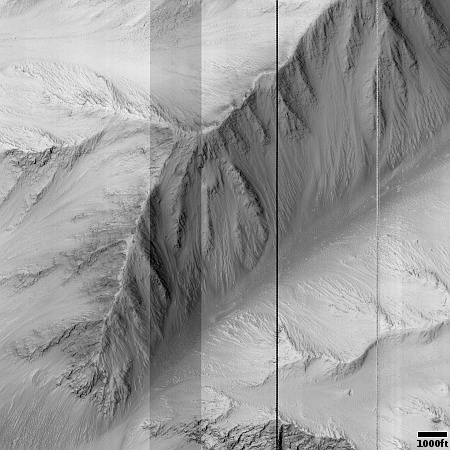

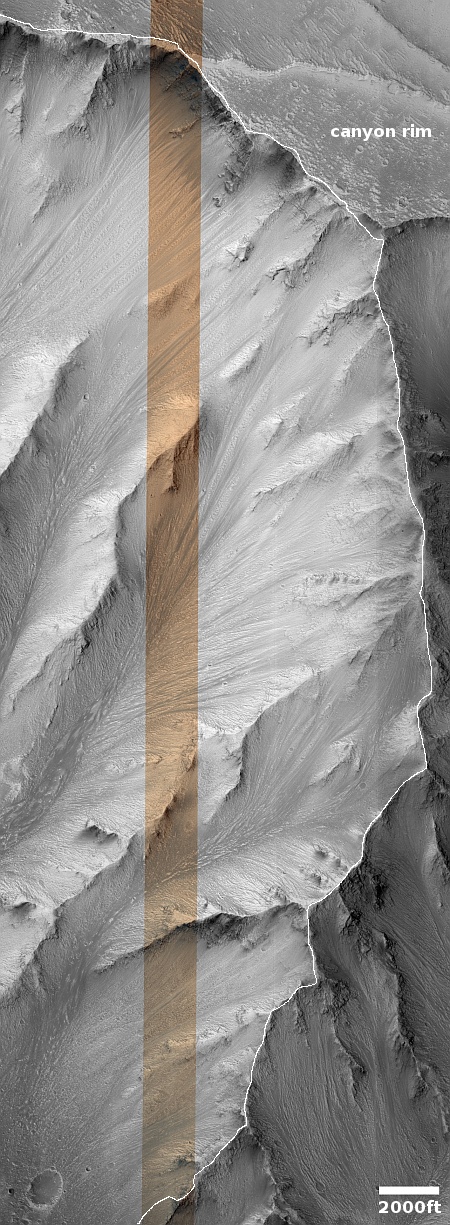

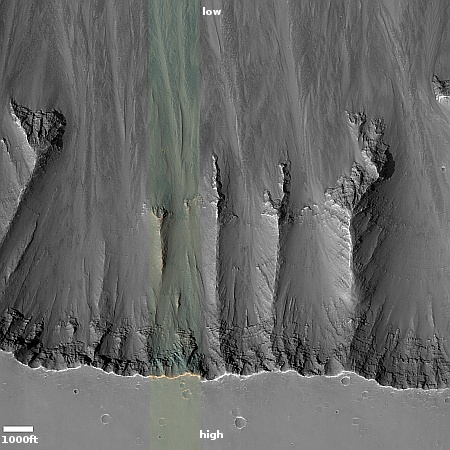

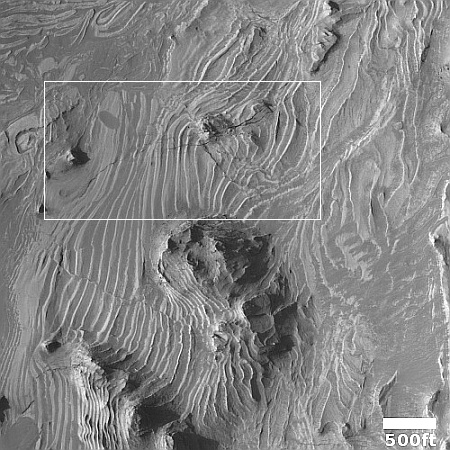

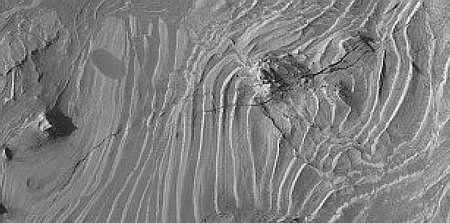

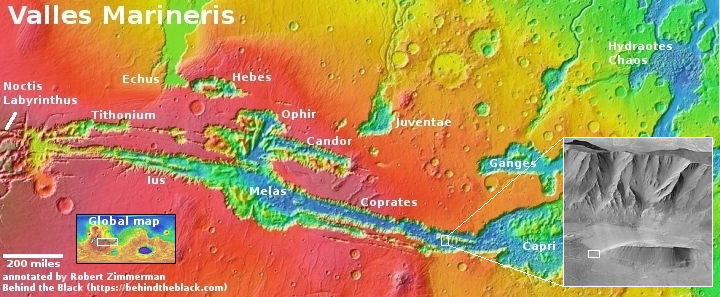

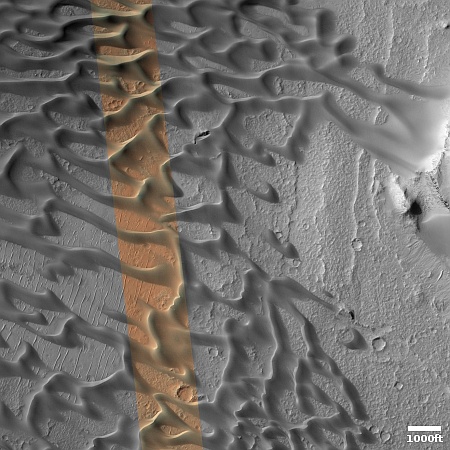

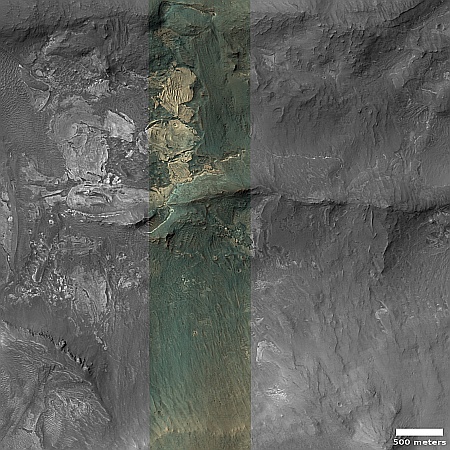

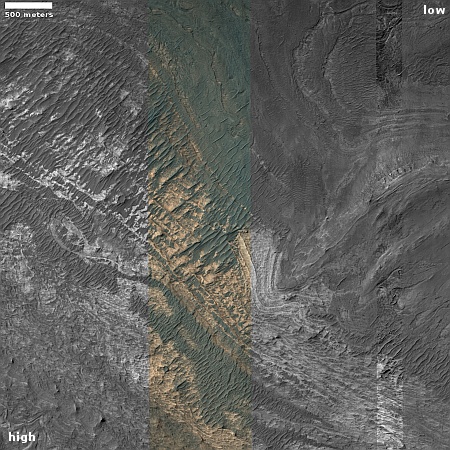

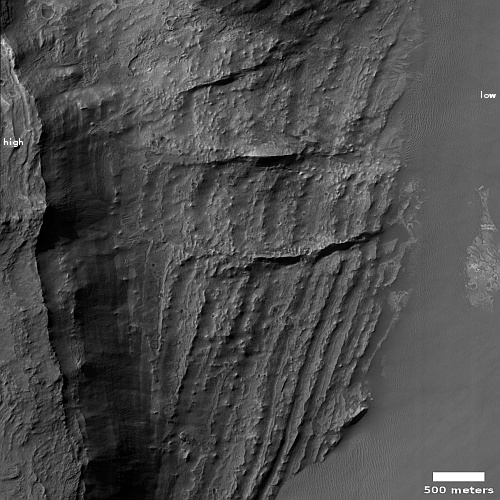

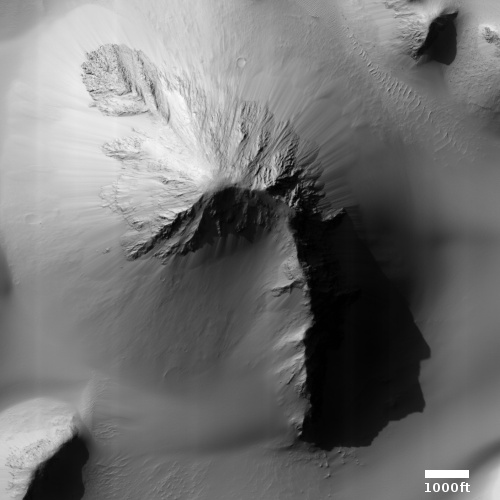

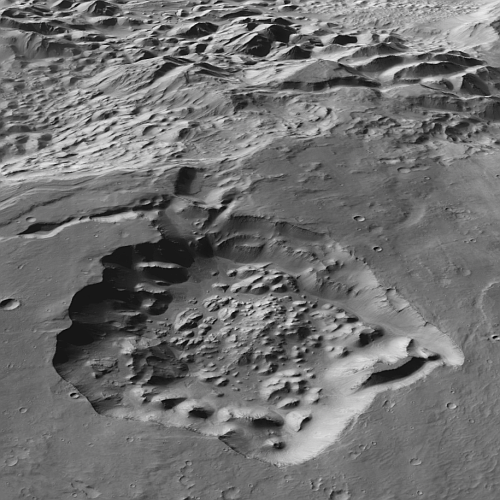

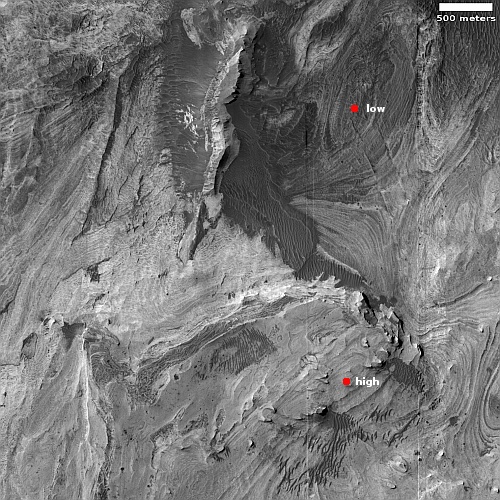

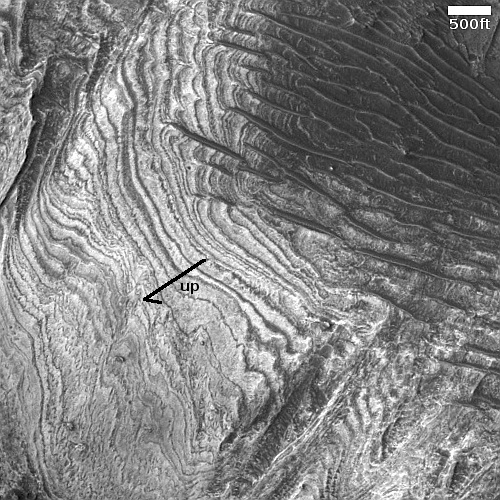

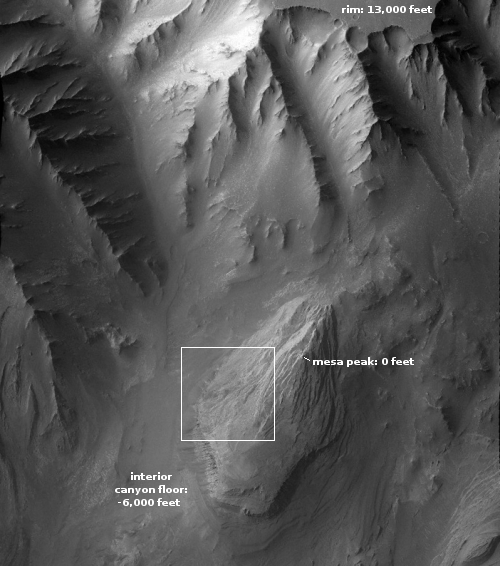

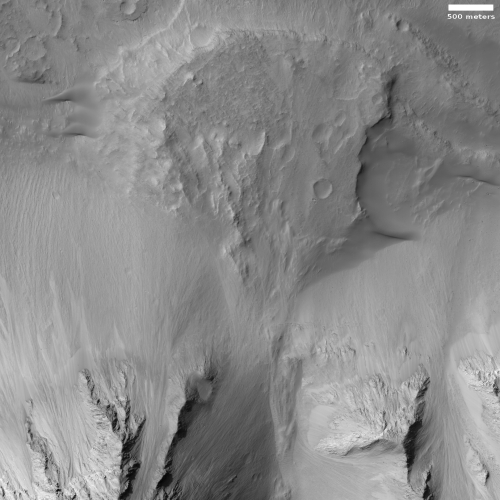

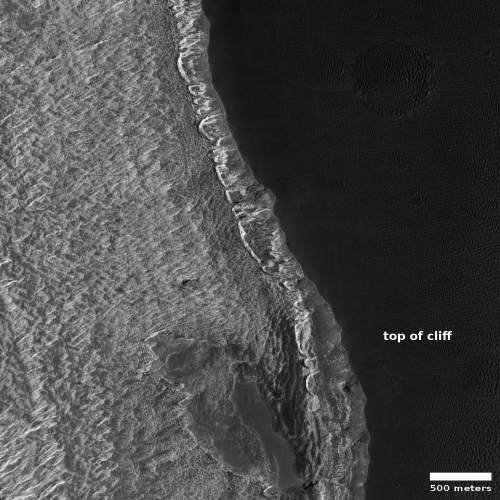

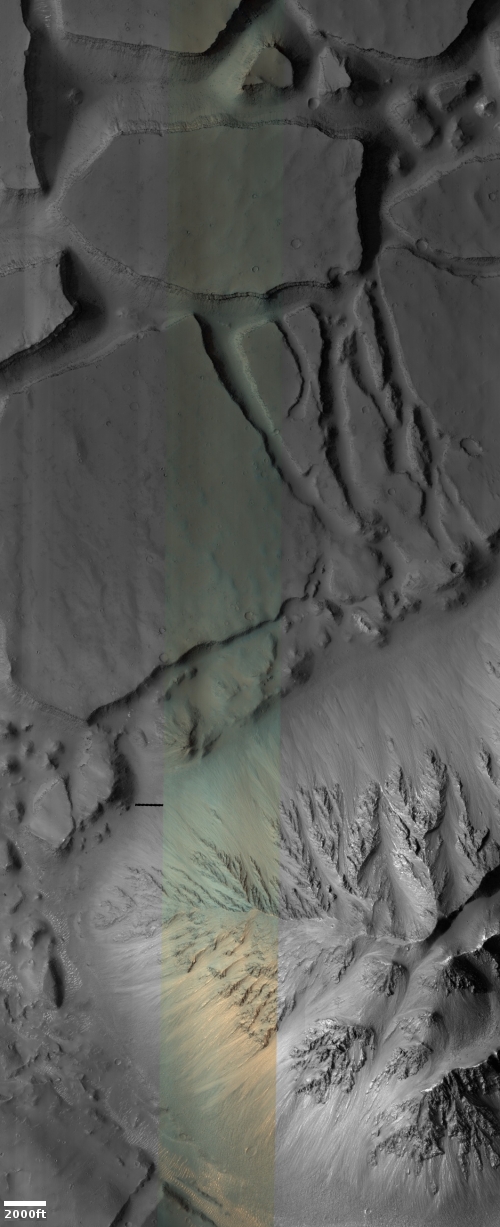

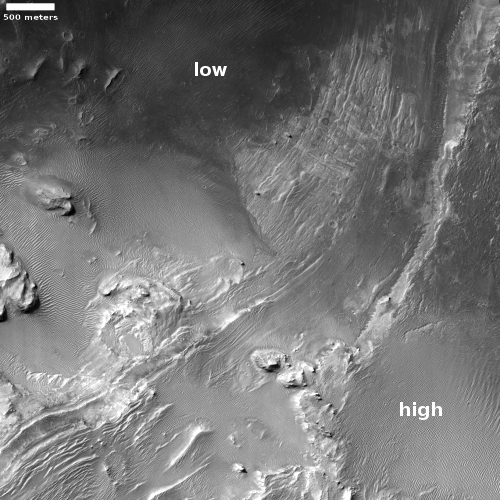

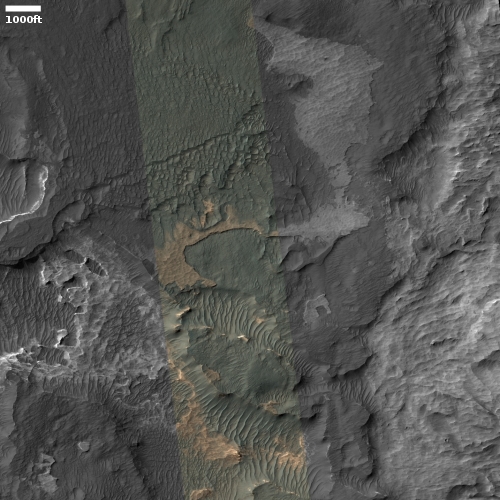

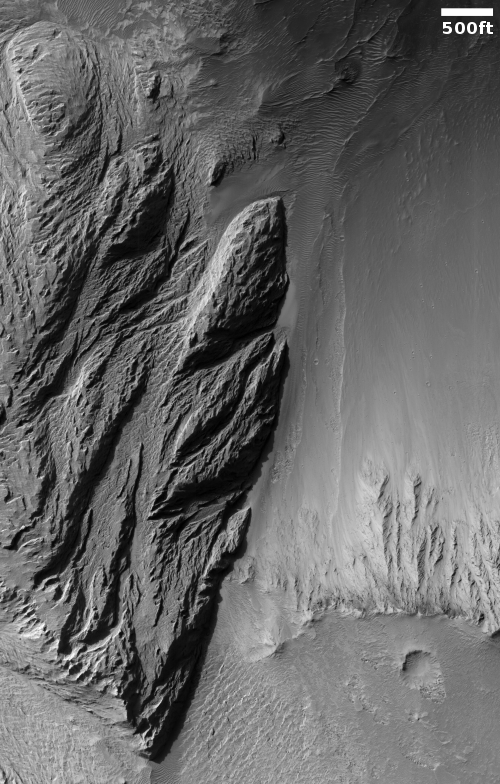

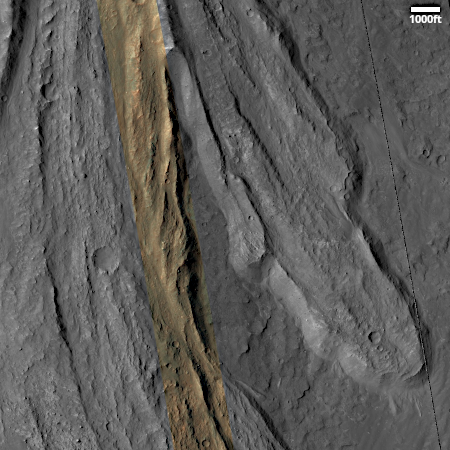

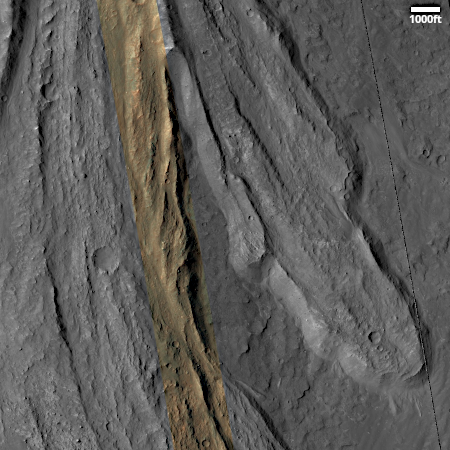

Cool image time! The picture to the right, cropped, reduced, and sharpened to post here, was taken on November 8, 2025 by the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). It shows only three miles of a ten-mile-long avalanche inside the solar system’s largest canyon, Valles Marineris.

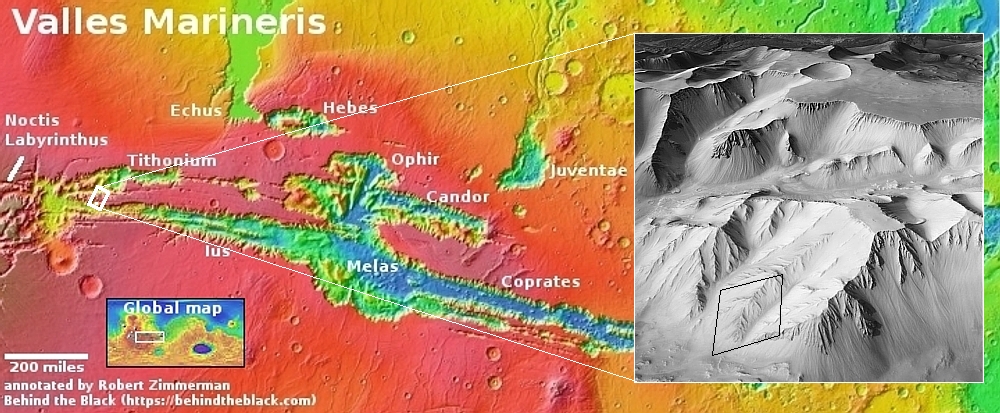

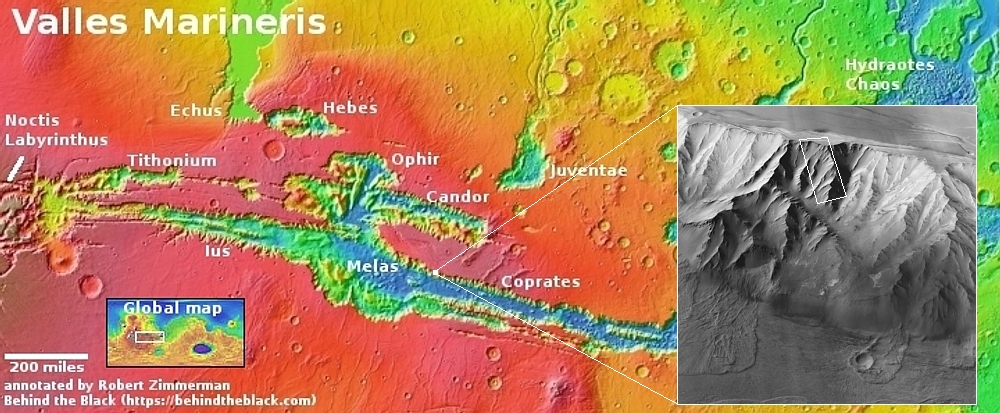

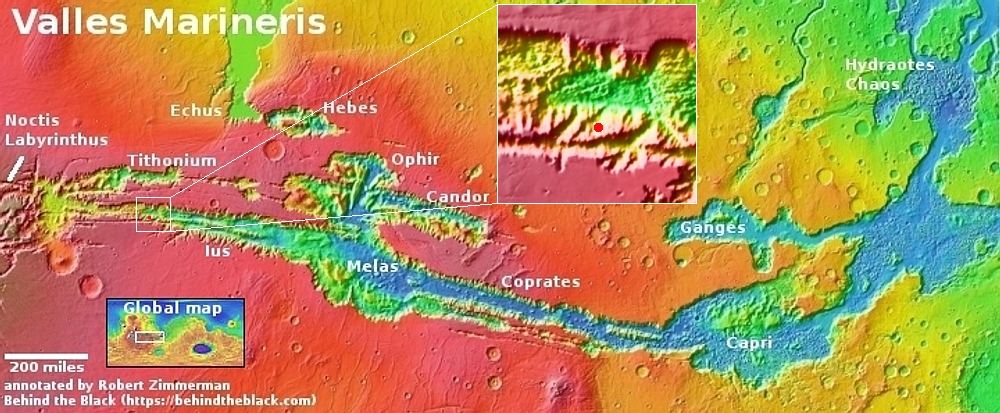

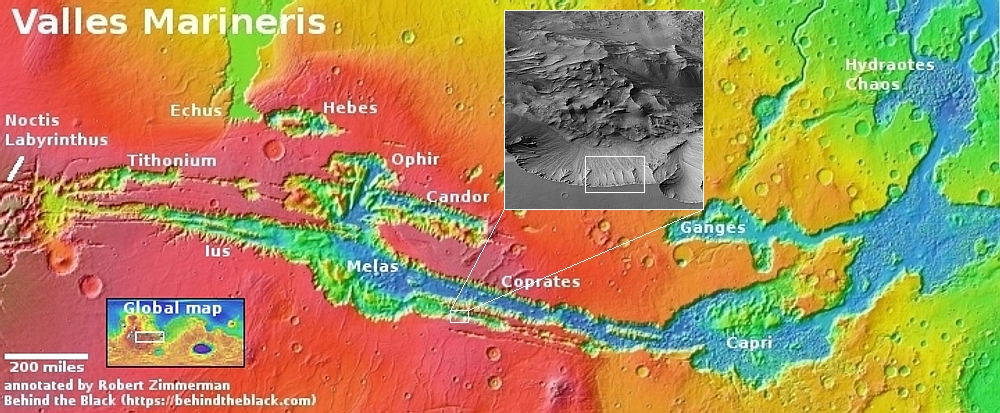

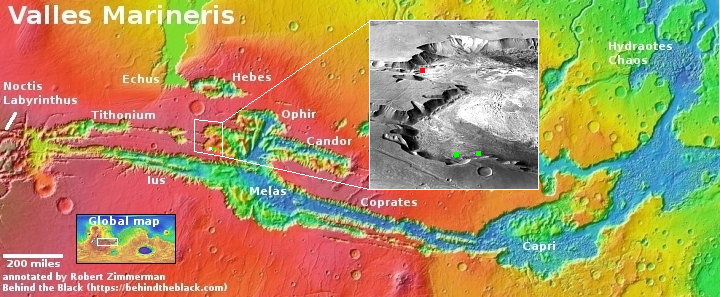

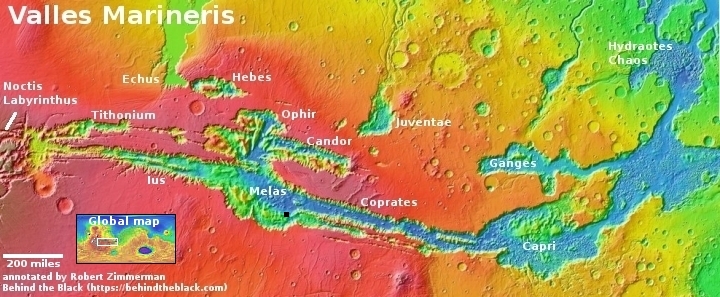

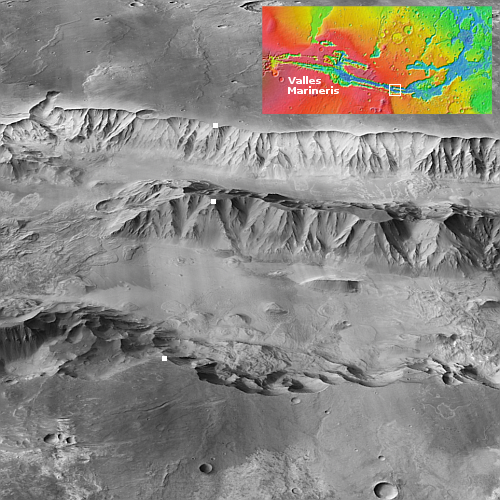

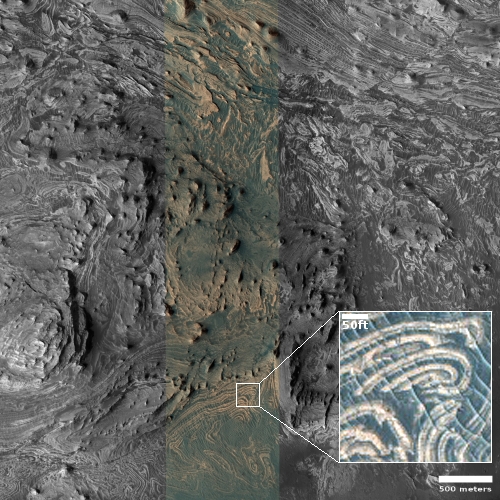

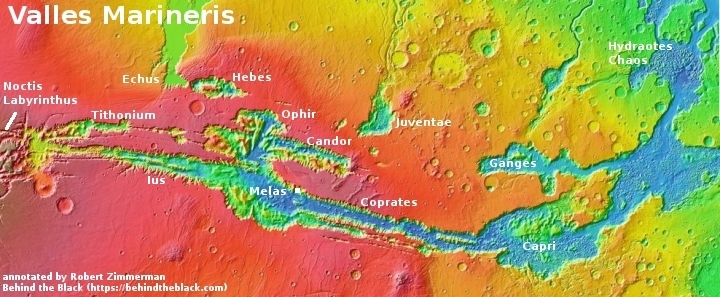

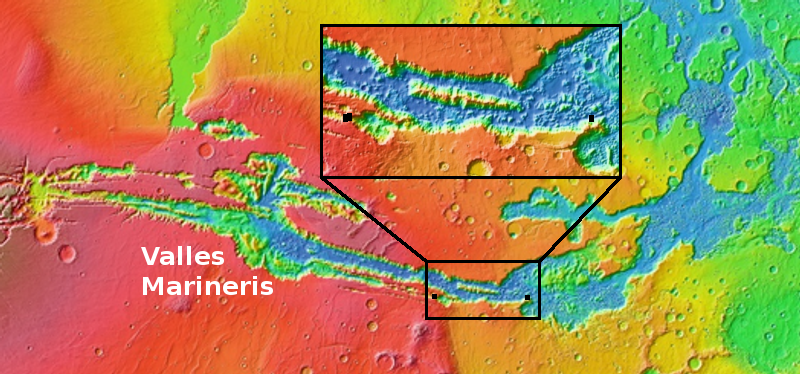

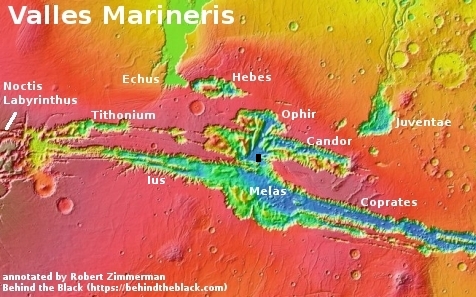

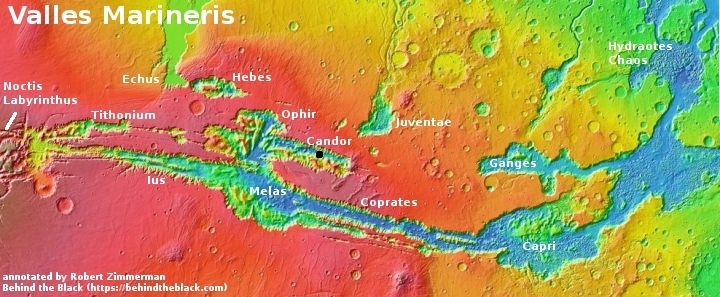

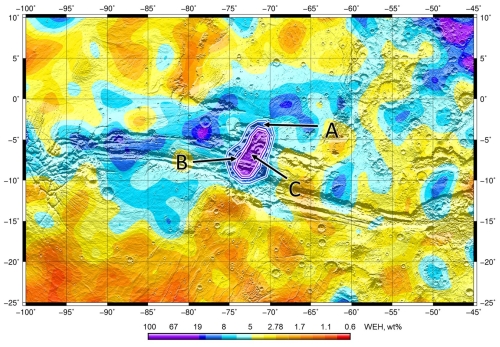

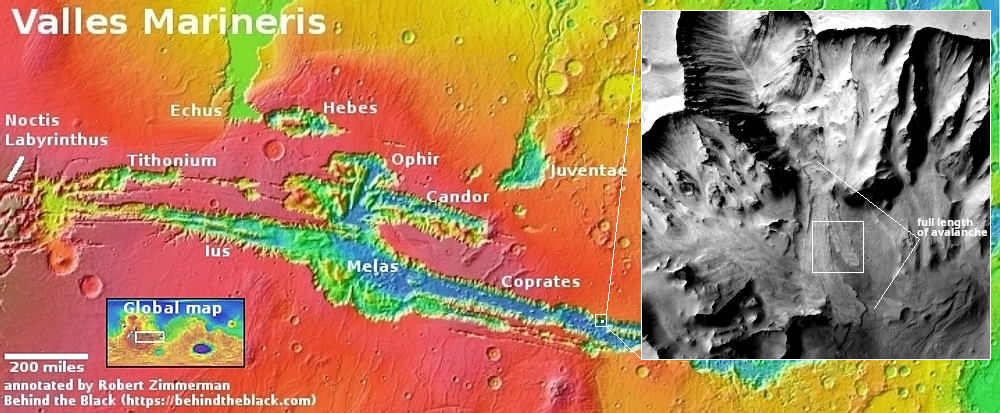

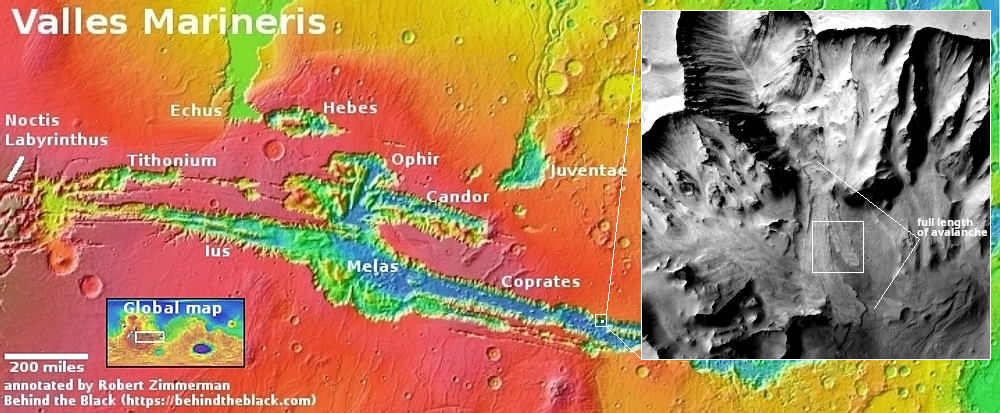

The white dot on the overview map above marks the location. In the inset the white rectangle indicates the area covered by the picture to the right. I have indicated the avalanche’s full extent beyond this.

Overall, the landslide fell about one mile along those ten miles. That there are about a dozen small craters on top of the slide tells us this happened quite a long time ago.

As always, the scale of Valles Marineris boggles the mind. Though this avalanche fell about 5,000 feet (the same depth of the south rim of the Grand Canyon), that drop only covered one fifth of Valles Marineris’s depth. At this point, from the rim to the floor the elevation difference is about 23,000 feet, which would place the rim among the 100 highest mountains on Earth. And of course, this is only one small spot in this gigantic canyon that runs 2,500 miles east-to-west, with its depth about the same that entire length.

Click for original image.

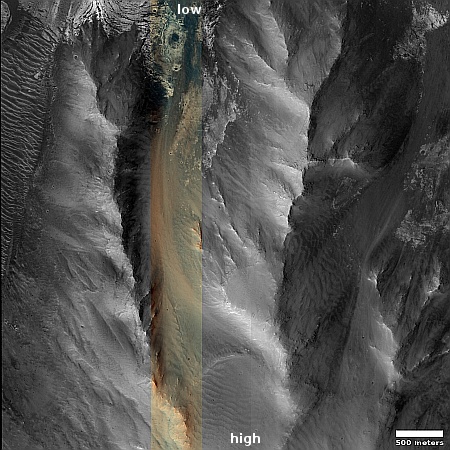

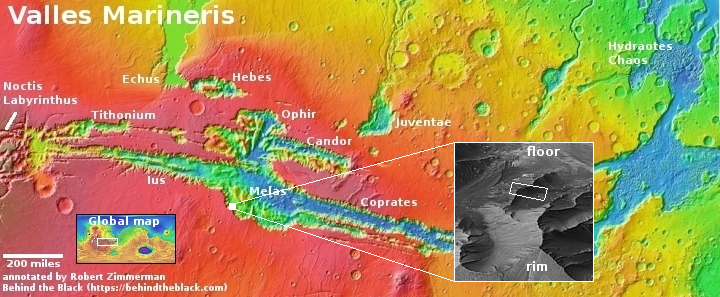

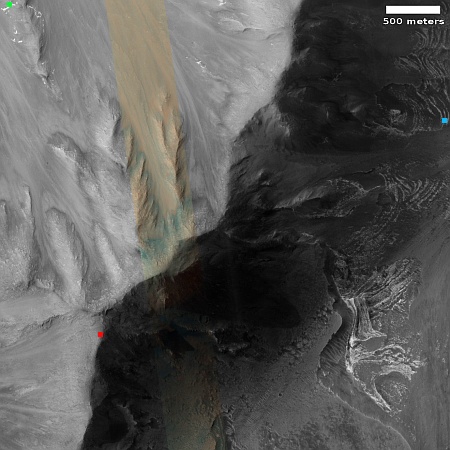

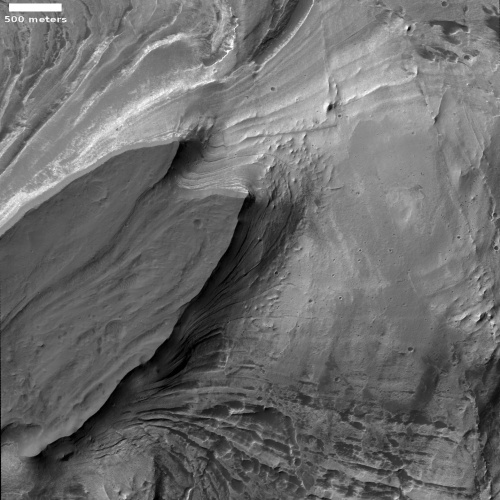

Cool image time! The picture to the right, cropped, reduced, and sharpened to post here, was taken on November 8, 2025 by the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). It shows only three miles of a ten-mile-long avalanche inside the solar system’s largest canyon, Valles Marineris.

The white dot on the overview map above marks the location. In the inset the white rectangle indicates the area covered by the picture to the right. I have indicated the avalanche’s full extent beyond this.

Overall, the landslide fell about one mile along those ten miles. That there are about a dozen small craters on top of the slide tells us this happened quite a long time ago.

As always, the scale of Valles Marineris boggles the mind. Though this avalanche fell about 5,000 feet (the same depth of the south rim of the Grand Canyon), that drop only covered one fifth of Valles Marineris’s depth. At this point, from the rim to the floor the elevation difference is about 23,000 feet, which would place the rim among the 100 highest mountains on Earth. And of course, this is only one small spot in this gigantic canyon that runs 2,500 miles east-to-west, with its depth about the same that entire length.