Windswept Martian volcanic ash?

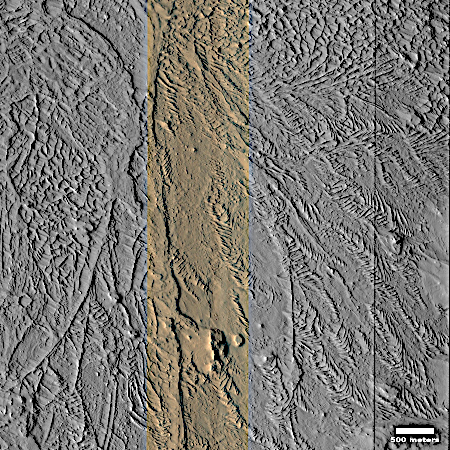

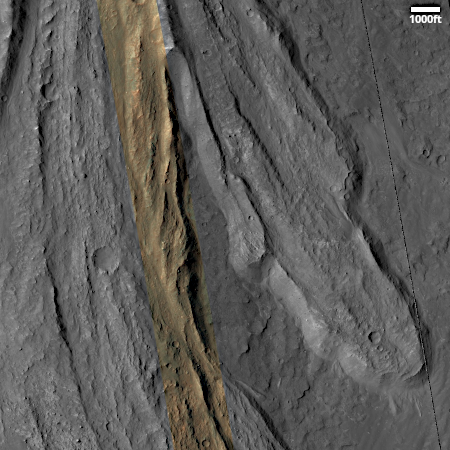

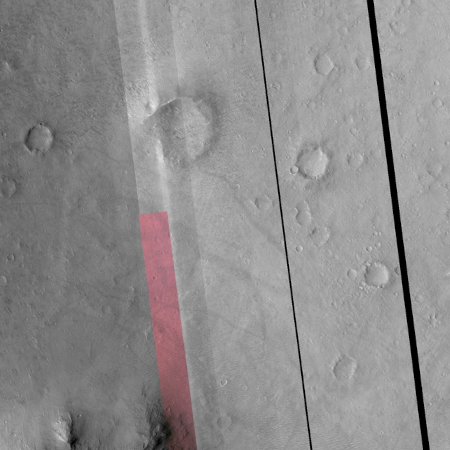

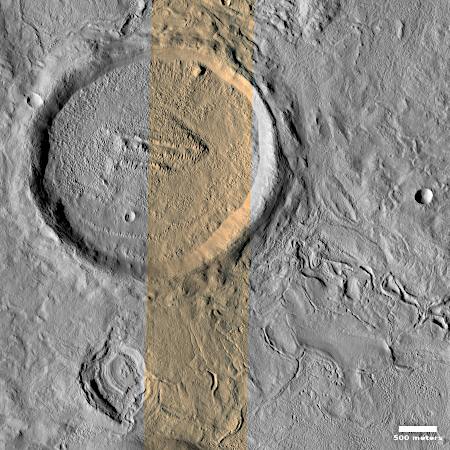

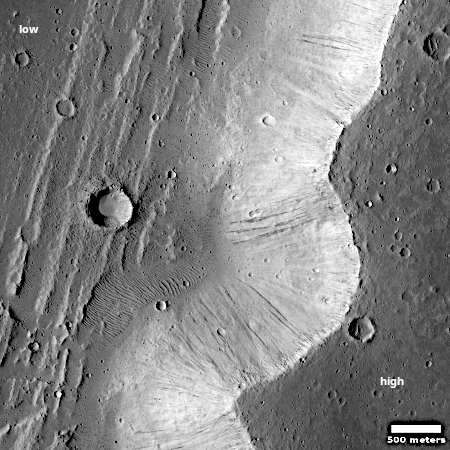

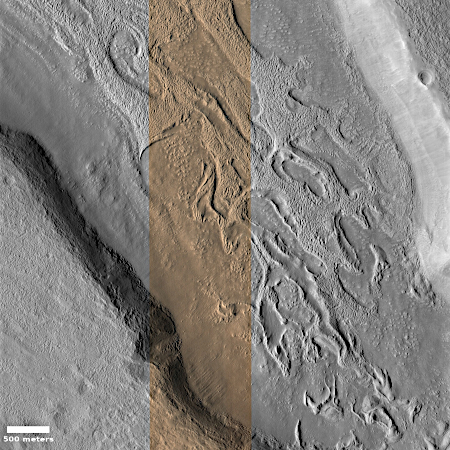

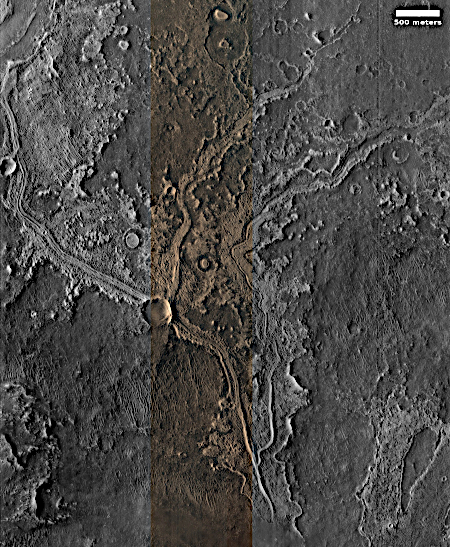

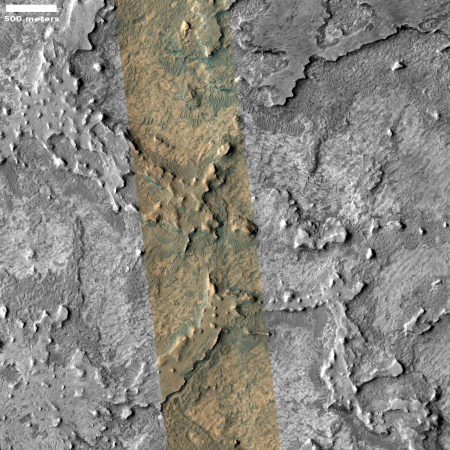

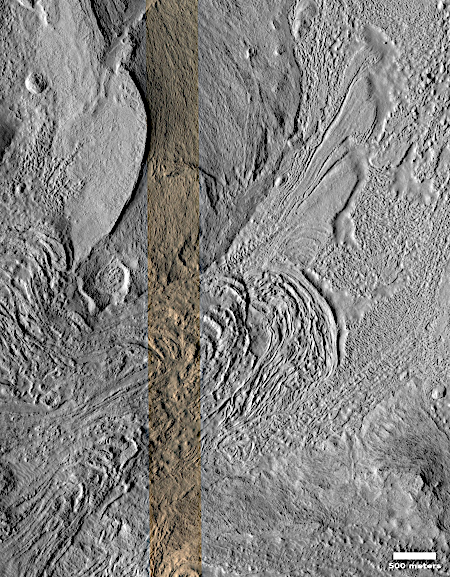

Cool image time! The picture to the right, rotated, cropped, reduced, and sharpened to post here, was taken on November 30, 2025 by the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO).

The science team labels this simply as “Features,” the vagueness of which I can understand after digging in to get a better idea of the location and geography.

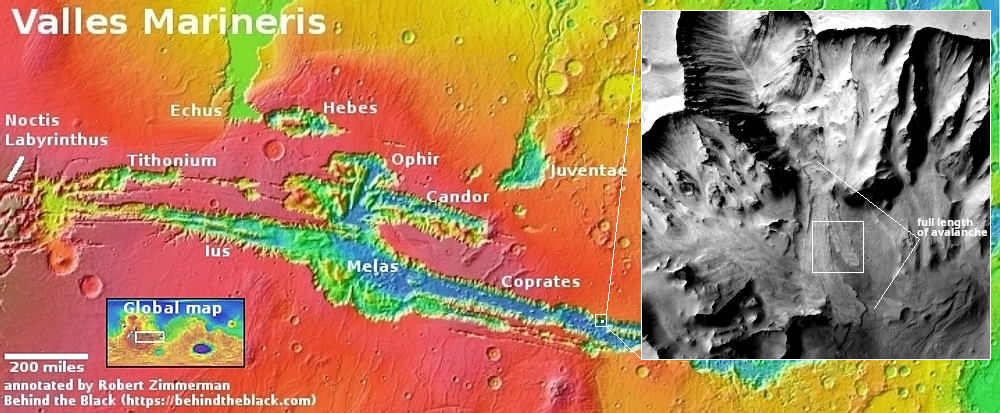

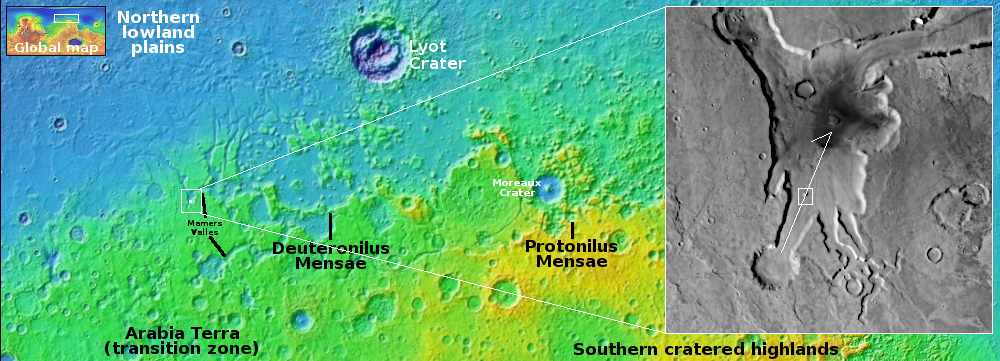

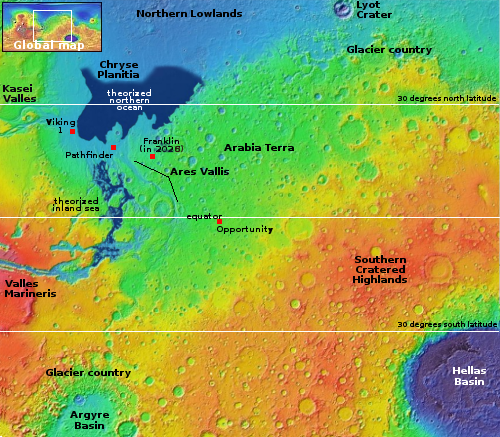

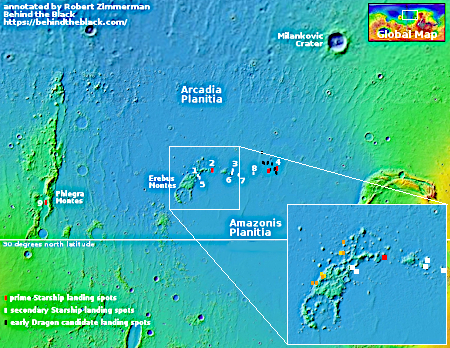

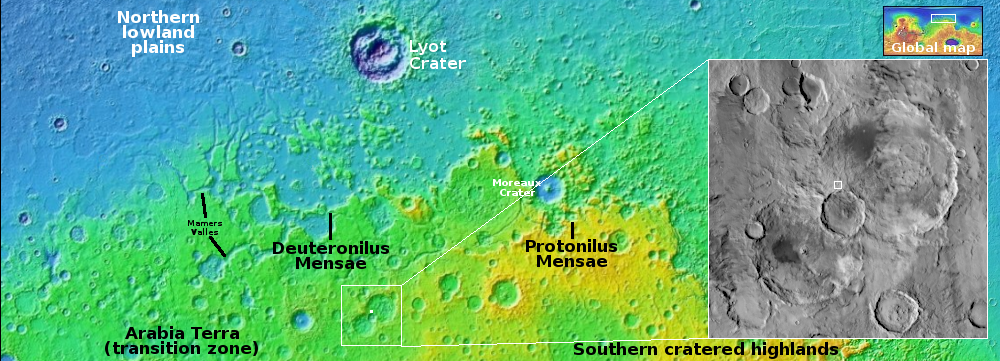

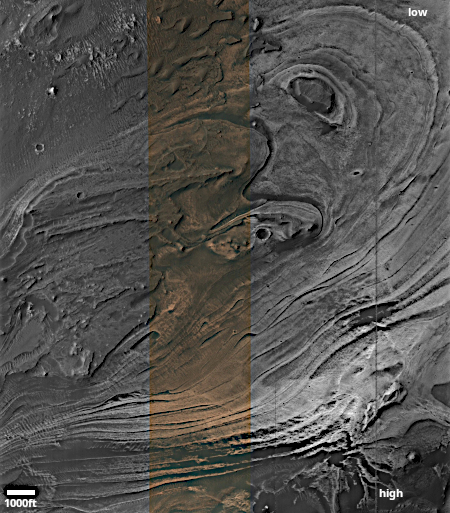

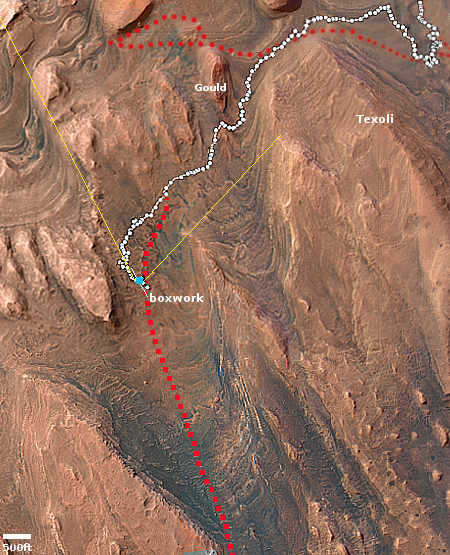

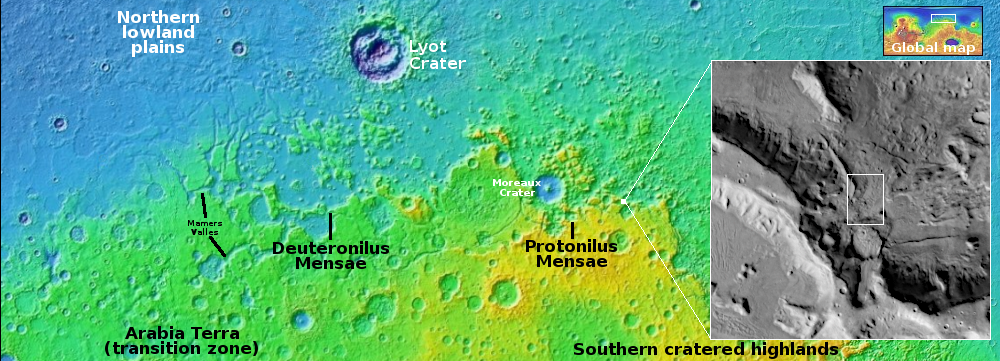

The location, as shown by the white dot on the overview map below, is inside the Medusa Fossae Formation, the largest volcanic ash field on Mars that is thought to be the source of much of the red planet’s dust. That ash field is large and very deep, and was put down more than a billion years ago when the giant volcanoes of Mars were active and erupting. Thus it is well layered, and many images of that ash field show that layering exposed by the eons of Martian wind scouring its surface.

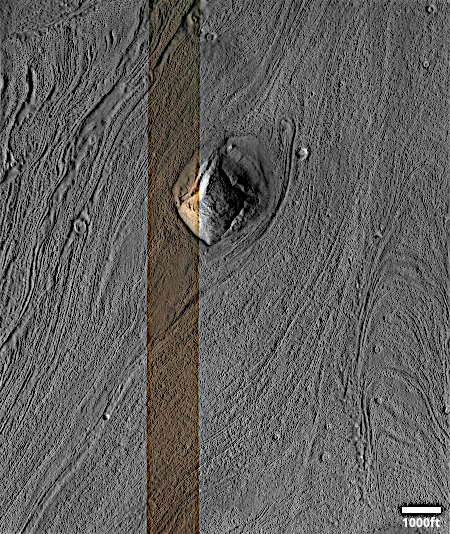

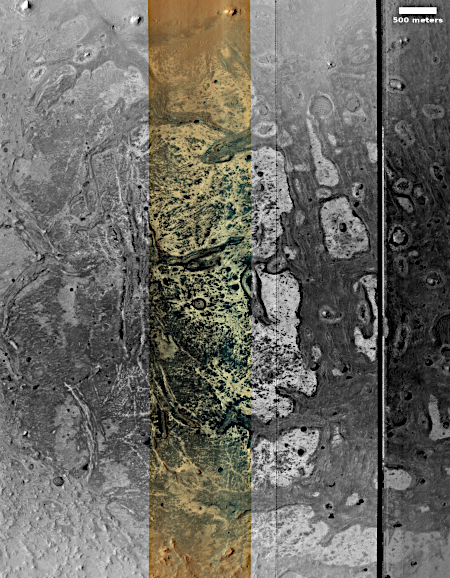

In this case, that scouring appears to have produced this feathery surface, though the origin of those ridges might have instead come from volcanic flows that are now hardened. Or we could be looking at ancient channels produced by ice or water, though that would have to have been a very long time ago, as this image is located in the Martian dry tropics, where no near surface ice presently exists.

» Read more

Cool image time! The picture to the right, rotated, cropped, reduced, and sharpened to post here, was taken on November 30, 2025 by the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO).

The science team labels this simply as “Features,” the vagueness of which I can understand after digging in to get a better idea of the location and geography.

The location, as shown by the white dot on the overview map below, is inside the Medusa Fossae Formation, the largest volcanic ash field on Mars that is thought to be the source of much of the red planet’s dust. That ash field is large and very deep, and was put down more than a billion years ago when the giant volcanoes of Mars were active and erupting. Thus it is well layered, and many images of that ash field show that layering exposed by the eons of Martian wind scouring its surface.

In this case, that scouring appears to have produced this feathery surface, though the origin of those ridges might have instead come from volcanic flows that are now hardened. Or we could be looking at ancient channels produced by ice or water, though that would have to have been a very long time ago, as this image is located in the Martian dry tropics, where no near surface ice presently exists.

» Read more