Two weeks under water

An evening pause: A clever way to extend research time under water. My only question in thinking about the experiments she was doing: What happens if it gets cooler?

Hat tip Cotour.

An evening pause: A clever way to extend research time under water. My only question in thinking about the experiments she was doing: What happens if it gets cooler?

Hat tip Cotour.

Today was supposed to have been the last day at the cancelled 51st annual Lunar & Planetary Science conference. As such, only a half day of presentations had been scheduled in order to give participants the option of returning home sooner.

While many of the abstracts of the planned-but-now-cancelled presentations were on subjects important to the scientists but not so interesting to the general public, two sessions, one on Martian buried glaciers/ice and a second focused on Mercury, would have made the day very worthwhile to this science journalist, had I been there.

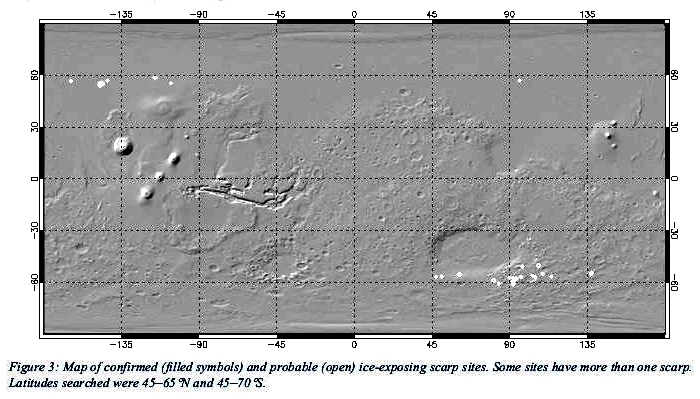

The map above, from the first abstract [pdf] of the Mars session, might possibly epitomize our present knowledge of ice/glaciers on Mars. It provides an update of the continuing survey of ice scarps in the high mid-latitudes of Mars (see the most recent post on Behind the Black from February 12, 2020). Clearly, the more they look, the more they find of these ice scarps, cliff faces with visible exposed pure ice layers that will be relatively easy to access.

But then, finding evidence of some form of buried ice on Mars is becoming almost routine. Of the thirteen abstracts in this Mars session, ten described some sort of evidence of buried ice or glaciers on Mars, in all sorts of places, with the remaining three abstracts studying similar Earth features for comparison. The scientists found evidence of water ice on the top of one of Mars’ largest volcanoes (abstract #2299 [pdf]), in faults and fissures near the equator (#1997 [pdf]), in the eastern margin of one of Mars’ largest deep basins (#3070 [pdf]), in Gale Crater (#2609 [pdf]), in the transition zone between the northern lowlands and southern highlands (#1074 [pdf]), and of course in the northern mid-latitude lowland plains (#2648 [pdf] and #2872 [pdf]).

The results tell us not that there is water ice on Mars, but that it is very plentiful, and that its presence and behavior (as glaciers, as snowfall, and as an underground aquifer) make it a major factor in explaining the geology we see on Mars. I’ve even begun to get a sense that among the planetary scientists researching Mars there is an increasing consideration that maybe ice formed many of the river-like features we see on the surface, not flowing water as has been assumed for decades. This theory has not yet become dominate or even popular, but I have been seeing mention of it increasingly in papers, in one form or another.

If this possibility becomes accepted, it would help solve many Martian geological mysteries, primary of which is the fact that scientists cannot yet explain how water flowed as liquid on the surface some time ago in Mars’ long geological history, given its theorized atmosphere and climate. If ice did the shaping, then liquid water (in large amounts) would not be required.

Now, on to the Mercury session.

» Read more

Cool image time! In prepping my report of the interesting abstracts from Friday of the cancelled 51st annual Lunar & Planetary Science conference (to be posted later today), I found myself reading an abstract [pdf] from the astrobiology session about the possibility of now inactive hot springs on Mars! This was such a cool image and possibility I decided to post it separately, first.

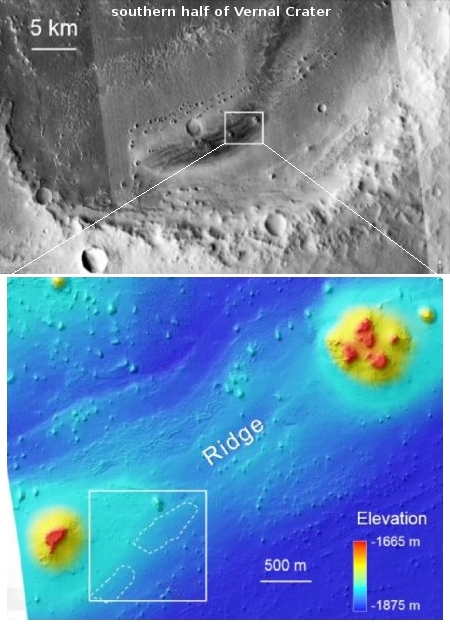

The top image to the right, cropped and expanded to post here, was taken by the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter in 2009. It shows some dark elliptical splotches inside the floor of a crater dubbed Vernal. The second image to the right, taken from the abstract, shows the context, with the top image a wide shot showing the southern half of Vernal Crater where these features are located, and the bottom image zooming into the area of interest. The white box focuses on the elliptical features seen in the first image above. From the abstract:

The elliptical features consist of concentric halos of high but varying albedo, where the highest albedo in each occurs in a small central zone that mimics the shape of the larger anomaly. Each feature is also traversed by circumferential fractures. Several similar tonal features extend for 5-6 km, on stratigraphic trend with the elliptical features. Hypotheses considered for the origin of the elliptical features included springs, mud/lava volcanoes, pingos, and effects of aeolian erosion, ice sublimation, or dust, but the springs alternative was most compatible with all the data.

The abstract theorizes that the small ligher central zone is where hot water might have erupted as “focused fluid injection” (like a geyser), spraying the surround area to form the dark ellipses.

I must emphasize that this hypothesis seems to me very tenuous. We do not really have enough data to really conclude these features come from a formerly active hot spring or geyser, though that certainly could be an explanation. In any case, the geology is quite intriguing, and mysterious enough to justify further research and even a future low cost mission, such as small helicopter drone, when many such missions can be launched frequently and cheaply.

Even as the space agency is about to launch a new rover to Mars, it is considering cutting operations for the rover Curiosity as well as considering shutting down its operation as soon as 2021.

Other ongoing missions are threatened by the administration’s fiscal year 2021 budget proposal. “The FY21 budget that the president just recently submitted overall is extremely favorable for the Mars program, but available funding for extended mission longevity is limited,” [said Jim Watzin, director of NASA’s Mars exploration program].

That request would effectively end operations of the Mars Odyssey orbiter, launched in 2001, and reduce the budget for Curiosity from $51.1 million in 2019 to $40 million in 2021, with no funding projected for that rover mission beyond 2021.

The penny-wise-pound-foolish nature of such a decision is breath-taking. Rather than continue, for relatively little cost, running a rover already in place on Mars, the agency will shut it down. And why? So they can initiate other Mars missions costing millions several times more money.

Some of the proposed cuts, such as ending the U.S. funding for Europe’s Mars Express orbiter, make sense. That orbiter has accomplished relatively little, and Europe should be paying for it anyway.

These decisions were announced during a live-stream NASA townhall that was originally to have occurred live at the cancelled Lunar & Planetary Science conference. I suspect its real goal is to garner support for more funding so that the agency will not only get funds for the new missions, it will be able to fund the functioning old ones as well.

Sadly, there would be plenty of money for NASA’s well-run planetary program if our Congress and NASA would stop wasting money on failed projects like Artemis.

In its panicky response to COVID-19, NASA is now requiring all workers to work from home, forcing the agency to suspend all in-house testing of SLS and Orion hardware.

NASA will temporarily suspend production and testing of Space Launch System and Orion hardware. The NASA and contractors teams will complete an orderly shutdown that puts all hardware in a safe condition until work can resume. Once this is complete, personnel allowed onsite will be limited to those needed to protect life and critical infrastructure.

We realize there will be impacts to NASA missions, but as our teams work to analyze the full picture and reduce risks we understand that our top priority is the health and safety of the NASA workforce.

This guarantees further delays to the first Artemis unmanned launch sometime in 2021. It also is par for the course for NASA’s entire effort to build this rocket. In just the past two weeks three different blistering inspector general reports have blasted different components of this project at NASA (overall management, construction of the launch systems, and development of software), proving that out-of-control cost overruns and endless delays in building SLS and Orion have been systemic throughout the agency.

Now they have shut down testing, even though the Wuhan virus is probably going to end up no more dangerous than the flu (now that treatment options exist).

It is now time for today’s virtual report from the non-existent 51st annual Lunar & Planetary Science conference, cancelled because of the terrified fear of COVID-19.

Unlike the previous three days, the bulk of the abstracts for presentations planned for today are more what I like to call “in-the-weeds” reports. The science is all good, but it is more obscure, the kind of work the scientists will be interested in but will generally hold little interest to the general public. For example, while very important for designing future missions, most of the public (along with myself) is not very interested in modeling studies that improve the interpretation of instrument data.

This does not mean there were no abstracts of interest. On the contrary. For today the most interesting sessions in the conference program centered on Mars as well as research attempting to better track, identify, and study Near Earth asteroids (NEAs).

The map above for example shows the location of Jezero Crater, where the rover Perseverance will land in 2021, under what one abstract [pdf] proposed might have been an intermittent ocean. The dark blue indicates where the topography suggests that ocean might have existed, while also indicating its shoreline. If it existed in the past, Perseverance might thus find evidence of features that were “marine in origin.” This ocean would also help explain the gigantic river-like delta that appears to pour into Jezero Crater from its western highland rim.

There were a lot of other abstracts looking closely at Jezero Crater, all in preparation for the upcoming launch of Perseverance in July, some mapping the site’s geology, others studying comparable sites here on Earth.

Other Mars-related abstracts of interest:

» Read more

More Boca Chica residents have accepted SpaceX purchase offers, and are finding other places to live.

While not all are thrilled with the circumstances, the article suggests that there is far more good will then unhappiness. It appears the excitement of what SpaceX is doing, and its willingness to give these residents special viewing privileges in the future, has done wonders to ease the pain for many of them for having to sell their homes.

It has also produced youtube channels providing 24 hour live streams of SpaceX operations.

Capitalism in space: The two reused fairing halves that SpaceX used in yesterday’s Falcon 9 Starlink launch were both successfully recovered.

Starlink V1 L5 is now the second time ever that SpaceX – or anyone, for that matter – has successfully reused an orbital-class launch vehicle payload fairing, while the mission also marked the first time that SpaceX managed to recover a reused Falcon fairing. The burn from booster issues certainly isn’t fully salved, as twin fairing catchers Ms. Tree and Ms. Chief both missed their fairing catch attempts, but both twice-flown fairing halves were still successfully scooped out of the Atlantic Ocean before they were torn apart.

The first reused fairing however was not recovered, making this recovery the first of used fairings. The company now has the ability to study them in order to better design future reusable fairings.

The article provides a lot of information about the difficulties of catching the fairings before they hit the water. It also notes that the reused fairings have all been fished out of the ocean, suggesting that in the end catching them in the ship’s nets will be unnecessary.

Capitalism in space: In announcing today it is beginning media accreditation for SpaceX’s first manned Dragon flight to ISS, the agency confirmed earlier reports from SpaceX that they are now aiming for a mid-to-late May launch.

Much can change before then. COVID-19 could get worse, shutting down all launches. The engine failure on yesterday’s successful Falcon 9 launch could require delays.

However, right now, things look good for May, which will be the first time since 2011 that Americans will launch from American soil on an American-built rocket, an almost ten year gap that has been downright disgraceful. Thank you Congress and presidents Bush and Obama! It was how you planned it, and is also another reason we got Trump.

A new report [pdf] released today from NASA’s inspector general has found more budget overruns and managerial issues relating to developing the ground software required by both Orion and SLS.

There are two software components involved, called SCCS and GFAS for brevity. This report focuses on the latter. A previous report found that “SCCS had significantly exceeded its initial cost and schedule estimates with development costs increasing approximately 77 percent and release of a fully operational version of the software slipping 14 months.” According to that previous report [pdf], that increase went from $117 million to $207 million.

As for GFAS:

Overall, as of October 2019 GFAS development has cost $51 million, about $14 million more than originally planned.

This report, as well as yesterday’s, are quite damning to the previous management of NASA’s manned program under Bill Gerstenmaier. It appears they could not get anything done on time and even close to their budget.

It also appears to me that the Trump administration has removed the reins from its inspector general offices. During the Obama administration I noticed a strong reticence in IG reports to criticize government operations. Problems as outlined in both yesterday’s and today’s reports would have been couched gently, to obscure how bad they were. Now the reports are more blunt, and are more clearly written.

Also, this sudden stream of releases outlining the problems in Artemis might be part of the Trump administration’s effort to shift from this government program to using private commercial companies. To do this however the administration needs Congressional support, which up to now has strongly favored funding SLS and Orion. Having these reports will strengthen the administration’s hand should it propose eliminating these programs, as it is now beginning to do with Gateway.

My virtual coverage of the cancelled 51st annual Lunar & Planetary Science conference continues today with a review of the abstracts of presentations that were planned for today, but unfortunately will never be presented.

As a side note, the social shutdown being imposed on America due to the panic over COVID-19 has some side benefits, as has been noted in a bunch of stories today. Not only will this possibly destroy the power the left has on college campuses as universities quickly shift to online courses, it will also likely put an end to the endless science conferences that are usually paid for by U.S. tax dollars. (That cost includes not just the expense of the conference, but the fees and transportation costs of the participants, almost all of whom get the money from either their government job or through research grants from the government.)

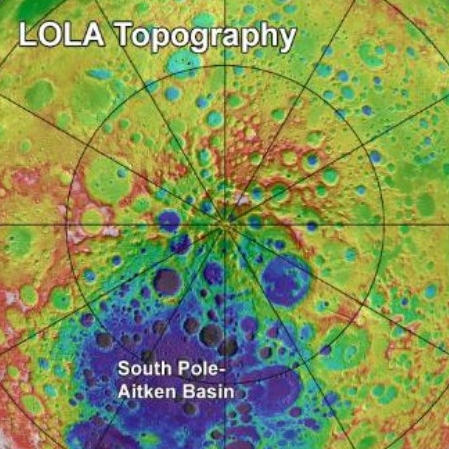

Anyway, for good or ill, the virus shut down the planetary conference in Texas this week, forcing me to post these daily summaries based not on real presentations where I would have interviewed the scientists and gotten some questions answered, but on their abstracts placed on line beforehand. Today, the three big subjects were the south pole of the Moon (as shown in the map above from one abstract [pdf], produced by one instrument on Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter [LRO]), the Martian environment, and Titan. I will take them it that order.

» Read more

Click for full resolution image.

Cool image time! Today the science team for the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) released a beautiful captioned image of a secondary impact of an object into the icy plains of Utopia Planitia, the northern lowlands northeast of where the rover Perseverance will land in 2021. The image to the right, cropped and reduced to post here, shows one of several secondary craters in the full image. As planetary scientist Alfred McEwen explains in the caption,

One interpretation [for the crater’s unusual appearance] is that the impact crater exposed nearly pure water ice, which then sublimated away where exposed by the slopes of the crater, expanding the crater’s diameter and producing a scalloped appearance. The small polygons are another indicator of shallow ice.

Note the dunes at the bottom of the crater. This has become a trap of wind-blown sand and dust. Note also how this secondary impact gives us a rough idea of the thickness of this ice, based on the area sublimated away.

There is a lot of relatively accessible ice in those northern lowlands, which is why SpaceX likes them for its possible landing site for Starship. That candidate site is in Arcadia Planitia, on the other side of Mars, but it is still in these same northern lowlands, where scientists have found lots of evidence of buried ice.

A new inspector general report [pdf] has found massive cost overruns in NASA over the building of the two mobile launch platforms the agency will use to launch its SLS rocket.

The original budget for the first mobile launch was supposed to be $234 million. NASA has now spent $927 million.

Worse, this platform will see limited use, as it was designed for the first smaller iteration of SLS, which NASA hopes to quickly replace with a more powerful version. Afterward it will become obsolete, replaced by the second mobile launch platform, now estimated to cost $486 million.

That’s about $1.5 billion just to build the launch platforms for SLS. That’s only a little less than SpaceX will spend to design, test, build, and launch its new Starship/Super Heavy rocket. And not only will Starship/Super Heavy be completely reusable, it will launch as much if not more payload into orbit as SLS.

But don’t worry. Our geniuses in Congress will continue to support SLS no matter the cost, even if it bankrupts NASA and prevents any real space exploration. They see its cost overruns, long delays, and inability to accomplish anything as a benefit, pumping money into their states and districts in order to buy votes.

Capitalism in space: SpaceX today successfully launched another sixty Starlink satellites into orbit, using a reused first stage for the fifth time, the first time they have done this. They also for the first time reused the fairing, for the second time. All told, the cost for this launch was reduced by approximately 70% by these reuses.

However, during launch one 1st stage Merlin engine shut down prematurely, the first time since 2012. You can see the consequence of this during the re-entry burn. After the burn, the rocket seems far more unstable then normal. Soon after the video cut out, and they must have missed the drone ship upon landing, making it a failure. They intend to do a full investigation before their next launch.

The leaders in the 2020 launch race:

5 China

5 SpaceX

3 Russia

2 Arianespace (Europe)

The U.S. now leads China 8 to 5 in the national rankings.

One additional detail: At the beginning of their live stream, they touted Starship/Super Heavy, and put out a call for engineers to apply to work for SpaceX.

The launch is embedded below the fold.

» Read more

Today was supposed to have been the second day of the week-long 51st annual Lunar & Planetary Conference, sadly cancelled due to fear of the Wuhan virus. As I had planned to attend, I am now spending each day this week reviewing the abstracts of the planned presentations, and giving my readers a review of what scientists had hoped to present. Because I am not in the room with these scientists, however, I cannot quickly get answers to any questions I might have, so for these daily reports my reporting must be more superficial than I would like.

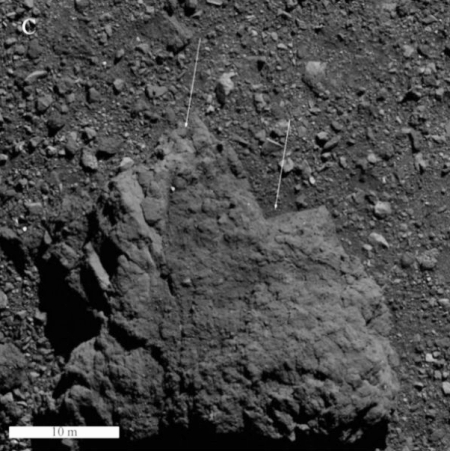

On this day the most significant reports came from scientists working on the probes to the asteroids Bennu and Ryugu as well as the probes to the Moon. The image to right for example is from one abstract [pdf] that studied the texture differences found fourteen boulders on Bennu. The arrows point to the contacts between the different textures, suggesting the existence of layers. Such layers could not have been created on Bennu. Instead, these rocks must have formed on a parent body large enough and existing long enough for such geological processes to take place. At some point that parent body was hit, flinging debris into space that eventually reassembled into the rubble pile of boulders that is Bennu.

Other abstracts from scientists from both the Hayabusa-2 mission to Ryugu and the OSIRIS-REx mission to Bennu covered a whole range of topics:

» Read more

The floating launch platform, built privately by an international partnership in the late 1990s and now owned by a Russian airline company, has arrived in Russia after a one month sea voyage from California.

Though supposedly owned now by S7, Sea Launch is really controlled by the Russian government and Roscosmos. They hope to use it as launch platform for their new Soyuz-5 rocket, intended as a family of rockets that would replace their venerable the Soyuz rocket originally developed in the 1960s.

Having a floating launch platform will also give Russia the ability for the first time to place satellites in low inclination orbits. The high latitudes of most of Russia means that any launches from any of their spaceports, including the one in Kazakhstan, will have a high inclination as well.

Russia on March 16 successfully launched a GPS-type Glonass satellite, using a Soyuz-2 rocket launched from a launchpad at they Plesetsk spaceport that had not been used in seventeen years.

The leaders in the 2020 launch race:

5 China

4 SpaceX

3 Russia

2 Arianespace (Europe)

The national ranking remains unchanged, with the U.S. leading China 7 to 5.

The first launch attempt of China’s newly upgraded Long March 7 rocket, dubbed the 7A, ended in failure today.

As is usual for China, very little concrete information was released, about the payload or the failure.

State news agency confirmed failure (in Chinese) just under two hours after launch, with no cause nor nature of the failure stated.

The Long March 7A is an effort by China to replace the use of rockets that use dangerous propellants and are launched in the interior of the country, sometimes dumping their first stages in habitable regions.

The Long March 7A is a variant of the standard Long March 7, which has flown twice. A 2017 mission to test the Tianzhou refueling spacecraft with Tiangong-2 space lab was its most recent activity. The launcher uses RP-1 and liquid oxygen propellant and could replace older models using toxic propellants.

It is also intended to launch from their new coastal spaceport in Wenchang. It did this today, though unsuccessfully.

Today I had planned on attending the first day of the 51st annual Lunar & Planetary Science Conference in the suburbs of Houston, Texas. Sadly, for the generally foolish and panicky reasons that is gripping America these days, the people in charge, all scientists, decided to cancel out of fear of a virus that so far appears generally only slightly more dangerous than the flu, though affecting far far far fewer people.

Anyway, below are some of the interesting tidbits that I have gleaned from the abstracts posted for each of Monday’s planned presentations. Unfortunately, because I am not in the room with these scientists, I cannot get my questions answered quickly, or at all. My readers must therefore be satisfied with a somewhat superficial description.

» Read more

A SpaceX launch attempt today to put sixty more Starlink satellites into orbit aborted at T minus Zero when the rocket’s computer software shut things down just after the engines began firing.

I have embedded the video below the fold. According to the broadcast, they had “a condition regarding engine power,” suggesting that one or more of the Merlin engines did not power up as expected and the computers reacted to shut the launch down because of this.

Not surprisingly, they have not yet announced a new launch date.

» Read more

According to the head of NASA’s manned program, the agency has revised its 2024 lunar landing plans so that the Lunar Gateway space station is no longer needed.

In a conversation with the NASA Advisory Council’s science committee March 13, Doug Loverro, NASA associate administrator for human exploration and operations, said he had been working to “de-risk” the Artemis program to focus primarily on the mandatory activities needed to achieve the 2024 landing goal.

…Later in the half-hour session, he said that means taking the lunar Gateway off the critical path for the 2024 landing. That was in part because of what he deemed a “high possibility” of it falling behind schedule since it will use high-power solar electric propulsion in its first module, the Power and Propulsion Element. “From a physics perspective, I can guarantee you we do not need it for this launch,” he said of the Gateway.

Loverro added that he wasn’t cutting Gateway, only pushing it back in order to prioritize their effort in getting to the lunar surface more quickly.

The Trump administration has been slowly easing NASA away from Gateway, probably doing so slowly in order to avoid upsetting some people in Congress (Hi there Senator Shelby!). They have probably looked at the budget numbers, the schedule, and the technical obstacles that are all created by Gateway, and have realized that they either can go to the Moon, or build a dead-end space station in lunar orbit. They have chosen the former.

Someday a Gateway station will be needed and built. This is not the time. I pray the Trump administration can force this decision through Congress.

Two stories today, one from Nature and the second from space.com, pushed the idea that China’s Mars orbiter/lander/rover mission is still on schedule to meet the July launch window.

A close read of both stories however revealed very little information to support that idea.

The Nature article provided some details about how the project is working around travel restrictions put in place because of the COVID-19 virus epidemic. For example, it told a story about how employees drove six scientific instruments by car to the assembly point rather than fly or take a train, thereby avoiding crowds.

What struck me however was that this supposedly occurred “several days ago,” and involved six science payloads that had not yet been installed on the spacecraft. To be installing such instrumentation at this date, only four months from launch, does not inspire confidence. It leaves them almost no time for thermal and vibration testing of the spacecraft.

The article also provided little information about the status of the entire project.

The space.com article was similar. Lots of information about how China’s space program is dealing with the epidemic, but little concrete information about the mission itself, noting “the lack of official comment on the mission.” Even more puzzling was the statement in this article that the rover “underwent its space environment testing in late January.”

I wonder how that is possible if those six instruments above had not yet been installed. Maybe the instruments were for the lander or orbiter, but if so that means the entire package is not yet assembled and has not been thoroughly tested as a unit. Very worrisome.

Posting today has been light because I was up most of the night dealing with a family health issue, meaning that I ended up sleeping for several hours during the day. All is well, nothing serious (it is NOT coronavirus), but it has left my brain and schedule very confused. Will likely take a good night’s sleep to get back to normal.

Cool image time! Or I should say a bunch of cool images! The photo on the right, rotated, cropped, reduced, and annotated by me, was taken by the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) on February 3, 2020. An uncaptioned image, it was entitled “Arabia Terra with Stair-Stepped Hills and Dark Dunes.” Arabia Terra is one of the largest regions of the transition zone on Mars between the northern lowland plains and the southern cratered highlands. It is also where Opportunity landed, and where Europe’s Rosalind Franklin rover will land, in 2022.

This image has so many weird and strange features, I decided to show them all, Below are the three areas indicated by the white boxes, at full resolution. One shows the black dunes, almost certainly made up of sand ground from volcanic ash spewed from a long ago volcanic eruption on Mars.

» Read more

Capitalism in space: According to ULA’s CEO, Tory Bruno, the company is on track to transition as planned from its Atlas 5 and Delta rockets to its new Vulcan rocket.

Just five Delta IV Heavy launches remain on the manifest, all NRO launches procured under the block buy Phase 1 methodology. Bruno expects the final Delta launch to occur in 2023 or 2024.

The workhorse of the ULA fleet, Atlas V, is expected to retire on a similar timeframe. Bruno says the launcher could be “done as early as 2022, or as late as 2024.” Atlas V will have to continue operations until its replacement, Vulcan, can be human-rated to launch the Boeing Starliner spacecraft.

…The first flight of Vulcan Centaur is on track for early 2021, with the first flight vehicle under construction, and more vehicles in flow, in ULA’s factory in Decatur, Alabama. Vulcan’s debut launch will carry the Astrobotic Peregrine lander to the moon for NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program. A second launch is currently planned for later that year, which will satisfy the Air Force certification requirement for Vulcan to launch military missions.

Bruno’s report is also good news for Blue Origin’s New Glenn rocket, since both will use Blue Origin’s BE-4 engine in their first stage. If ULA is on schedule, than Blue Origin also likely to be on schedule, meaning that come 2021 or so the U.S. will have at least three companies (including SpaceX) capable of putting large payloads into orbit. Moreover, Northrop Grumman is developing its OmegA rocket, which will compete for the same business.

The article also talks about the military’s launch procurement program, which supposedly will pick two of these launch companies to provide all military launches through the 2020s. That program however is certain to fail, as it will blacklist all other viable companies from bidding on military launches. I expect those companies will successfully sue and force the Space Force to accept bids from more than two companies.

And that is as it should be. Why the military wishes to limit bidding makes no sense, and is probably illegal anyway. As long as a company has a qualified rocket, its bids should be welcome.

Capitalism in space: According to one SpaceX official, they are now aiming for a May target date for their first manned Dragon mission to ISS, even as they will maintain a launch pace of one to two launches per month.

SpaceX president and chief operating officer Gwynne Shotwell [said] that she expects at least one to two launches per month in the near future, whether they be for customers or for SpaceX’s own internet-satellite constellation, Starlink. “And we are looking at a May timeframe to launch crew for the first time,” Shotwell continued. That launch, called Demo-2, will send NASA astronauts Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley to and from the International Space Station (ISS) aboard SpaceX’s Crew Dragon capsule.

At that pace SpaceX will complete between 12 to 24 launches for the year. They had predicted they would complete 21, so this is in line with that prediction.

The European Space Agency (ESA) today announced that they are delaying the launch of their ExoMars2020 rover mission until the next launch window in 2022

The press release says this will give them the time “necessary to make all components of the spacecraft fit for the Mars adventure.” Considering that the spacecraft’s parachutes have yet to have a successful high altitude test, that the entire spacecraft is not yet assembled, and that when they did the first thermal test of the rover the glue for the solar panel hinges failed, this seems that they need to do a lot of testing.

Overall the decision is smart. Better to give them the time to get this right then launch on time and have a failure.

At the same time, there appears to be something fundamentally wrong within the management of this project at ESA. This project was first proposed in 2001, and has gone through repeated restructurings and redesigns. Moreover, they began planning the rover for this 2020 launch in 2011, and after ten years were not ready for launch.

India’s manned space program has received a 70% cut in funding in that country’s most recent budget, according to one news story from India.

From the first link:

The human spaceflight program of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), called Gaganyaan, received only about 30% of the funds sought by the according to the Times of India. ISRO said it will find a way around the low budget, but details were not provided in the news report.

The plan has been to launch a unmanned mission late this year or early next year, with the 5-to-7-day manned mission to occur one year later.

Based on the article from India, it appears to me that these cuts are part of the negotiation process for determining ISRO’s budget, and are not yet firm. It also appears that the government is experiencing sticker shock. It wants a manned mission, but when it was told what it would cost it balked.

I suspect that it is highly unlikely that they will be able to fly the manned mission by 2022 with these cuts. The Modi government will either have to decide to spend the money, or significantly delay its human spaceflight effort.

Russian officials yesterday announced that they are delaying the first Proton launch in 2020 from March to May in order to replace components that during tests were found to be “mismatched.”

According to [Khrunichev Space Center Director General Alexei] Varochko, quality control tests revealed mismatch of one of the components’ parameters. “In order to ensure proper serviceability and guarantee the implementation of the Khrunichev Center’s liabilities, it was decided to replace the components set, including in the Proton-M carrier rocket, which is kept at the Baikonur space center, to put Express satellites into orbit,” he said.

Nor are they having issues only with their Proton rocket. Two days ago they announced a one month delay of a Soyuz rocket, set for launch for Arianespace, because of “an off-nominal malfunction … on a circuit board” in the Freget-M upper stage. Rather than replace the component, they have decided to replace the entire stage

Proton is built by the Khrunichev facility. Freget-M is built by the Lavochkin facility. For both to have issues like this suggests once again that Russia’s aerospace industry continues to have serious quality control problems in its manufacturing processes. The one bright spot is that they are at least finding out about the problems prior to launch.

Cool image time! To understand what created the vastly strange and alien Martian surface, it will be necessary for scientists to monitor that surface closely for decades, if not centuries. To the right is one small example. Taken by the high resolution camera of Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) and rotated, cropped, and reduced to post here, it shows a dune field inside a crater in the southern cratered highlands of Mars. Craters have been found to be great traps for dust and sand on Mars. Once the material is blown inside, the winds are not strong enough to lift the material out above the surrounding rims. Thus you often get giant dunes inside craters, as we see here.

What makes this location of interest to planetary scientists is the changing surface of these dunes. They have been monitoring the location since 2009. In 2013, the MRO science team released a captioned photograph, the second image to the right, also rotated, cropped, and reduced by me to match the same area in the top image. In that caption planetary scientist Corwin Atwood-Stone of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory in Arizona wrote,

This area was previously imaged in August 2009, about two Mars years ago, and in that image dust devil tracks were also visible. However the tracks visible now are completely different from the earlier ones. This tells us that there has been at least one dust storm since then to erase the old tracks, and lots of dust devil activity to create the new ones.

Since then the MRO science team has taken repeated images of this location to monitor how the dust devil tracks change, as well as monitor possible changes to the dunes themselves, including avalanches. The newest image above shows the result of the global dust storm last year. It wiped out the dust devil tracks entirely.

The newer image was entitled, “Monitor Dune Avalanche Slopes,” but I couldn’t find any examples. Based on published research, I am sure there is something there, even if I couldn’t find them. Maybe my readers have a better eye than I.