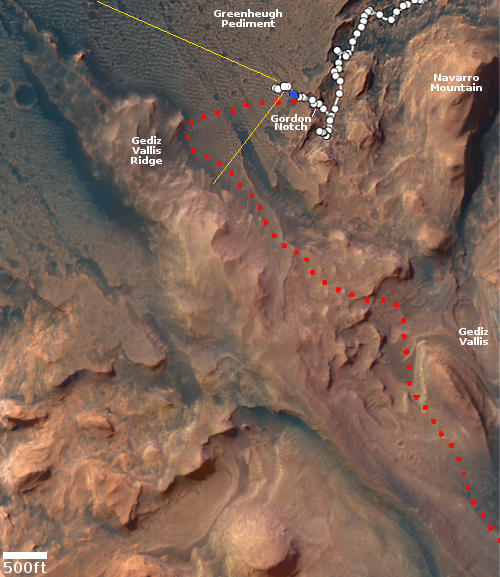

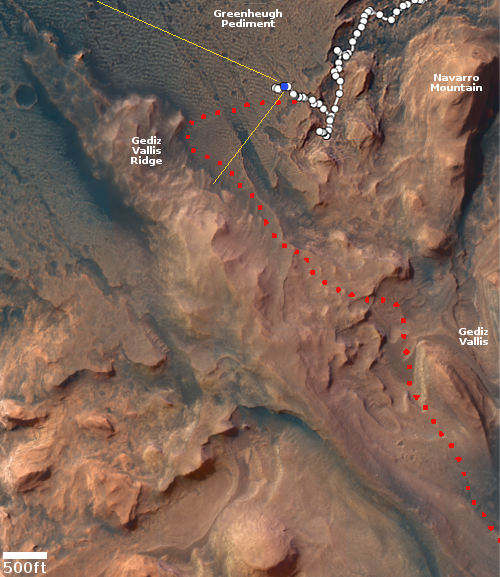

Martian mountains, near and far

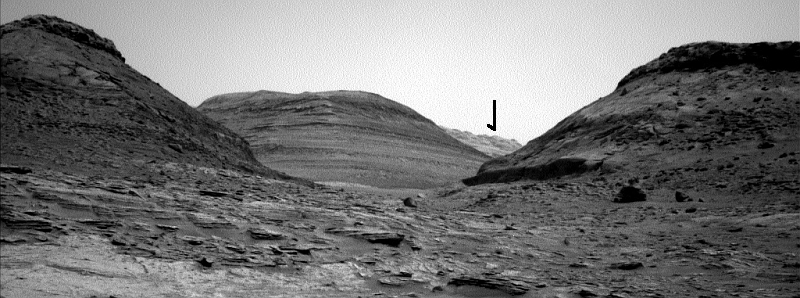

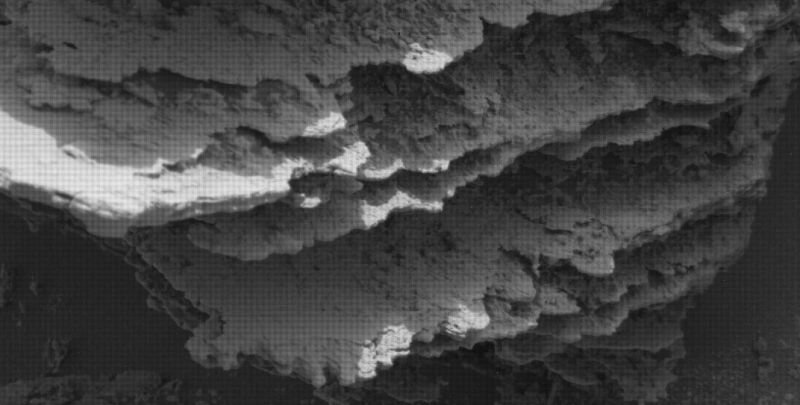

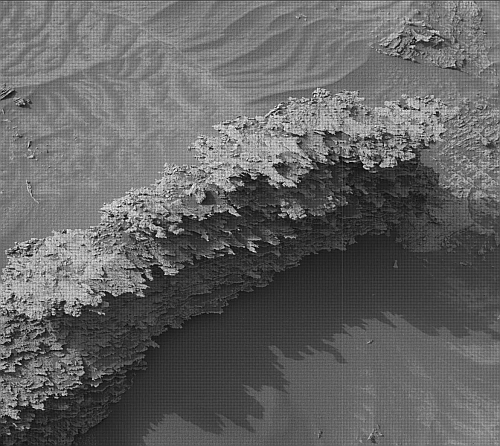

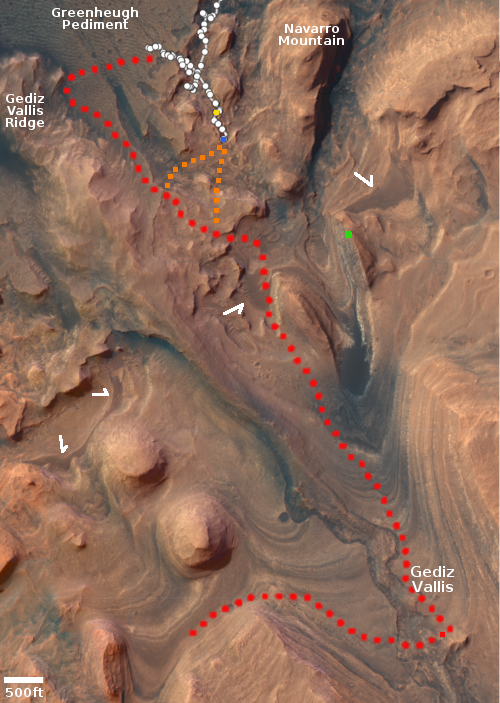

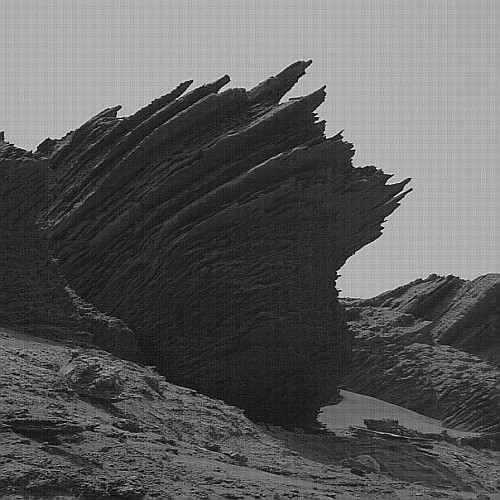

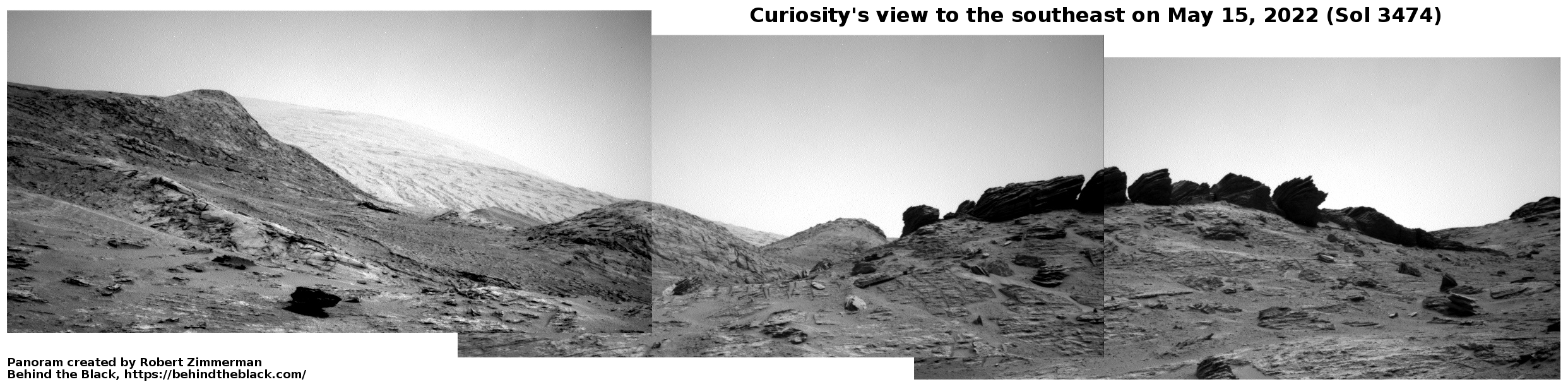

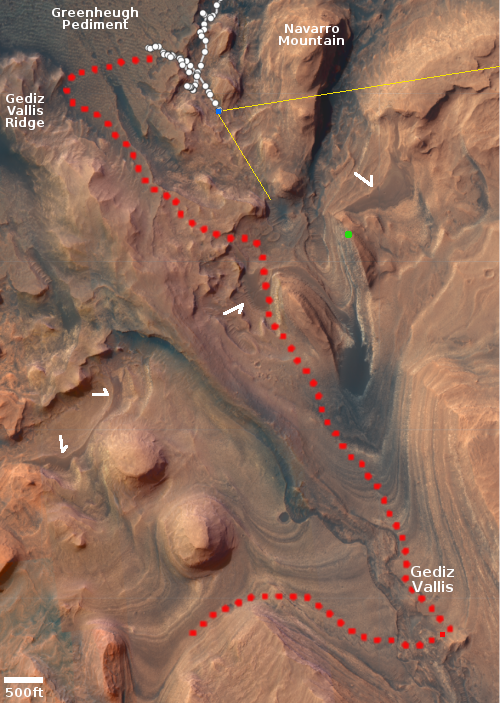

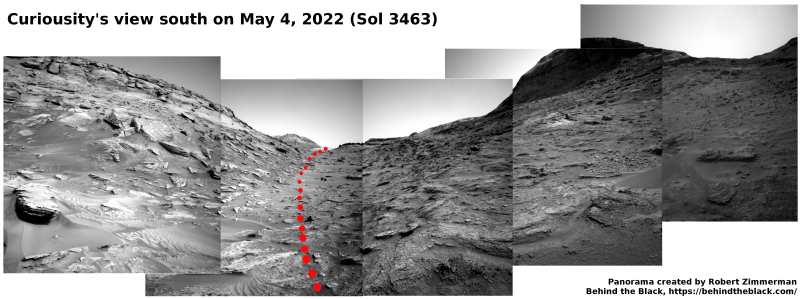

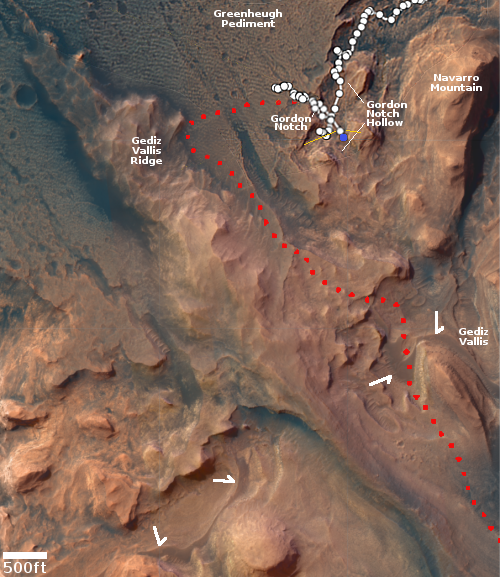

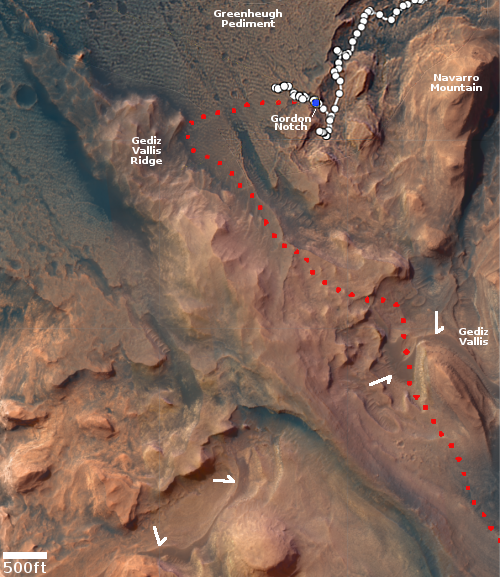

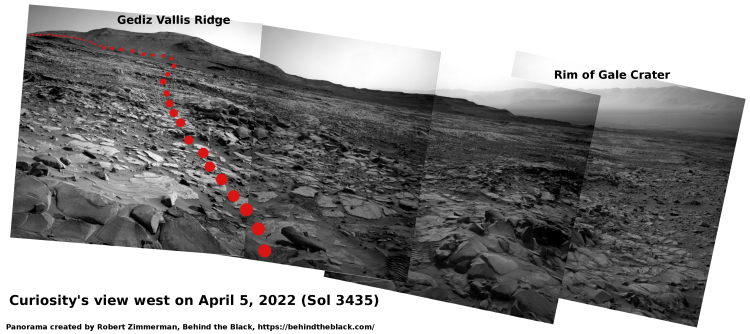

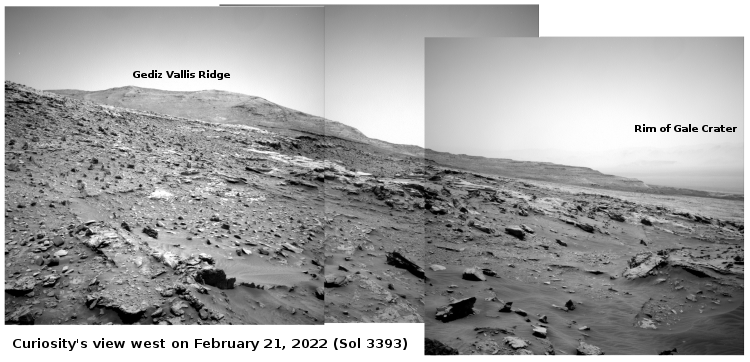

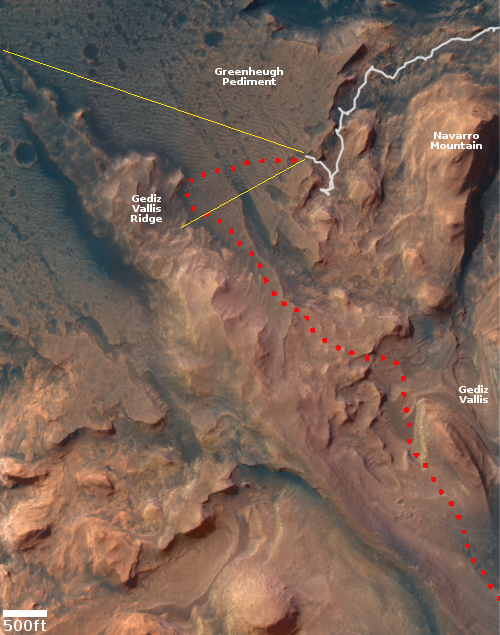

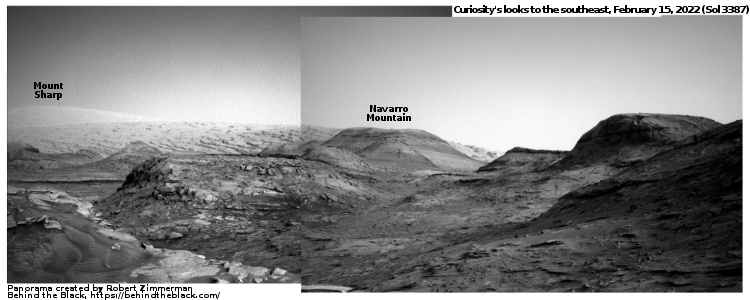

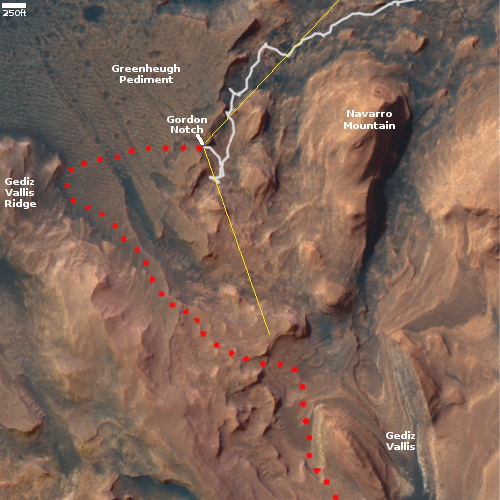

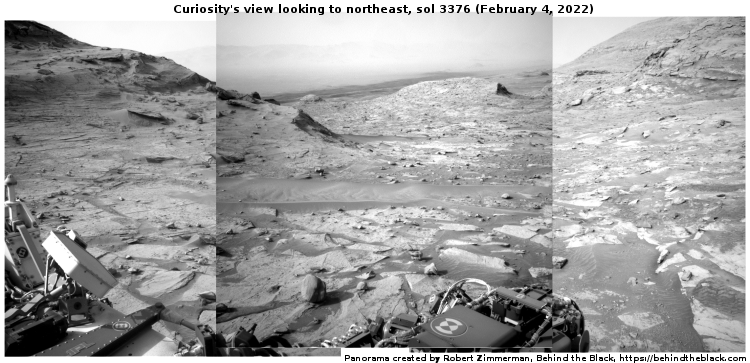

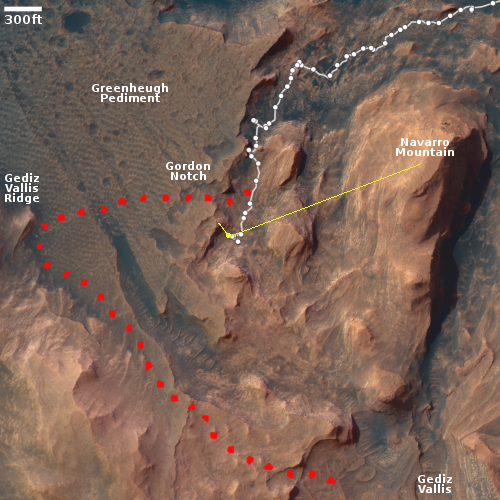

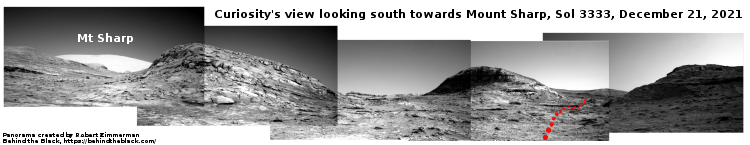

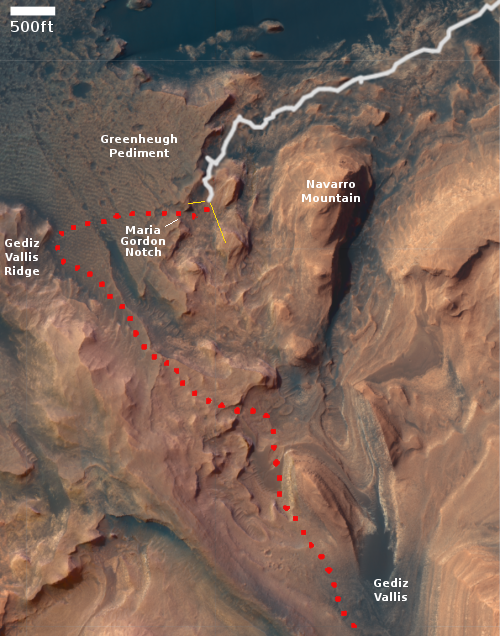

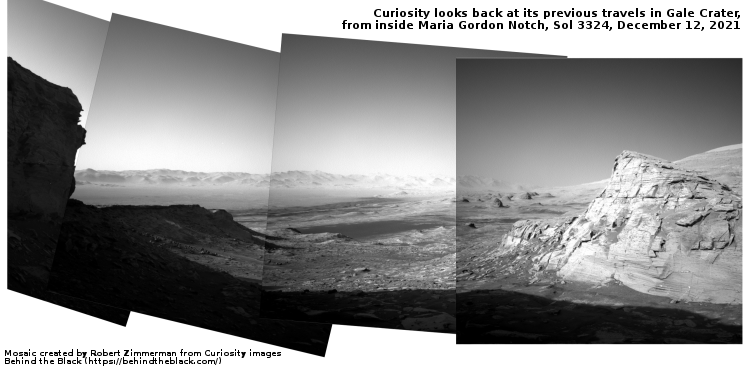

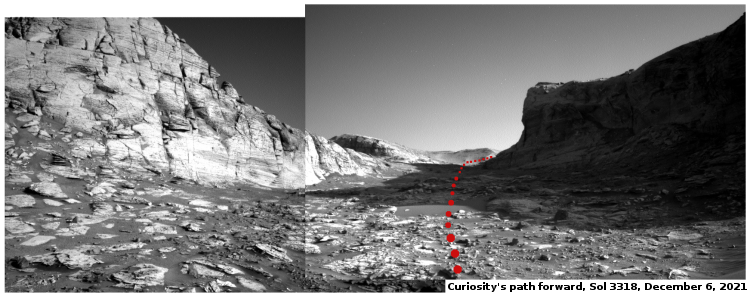

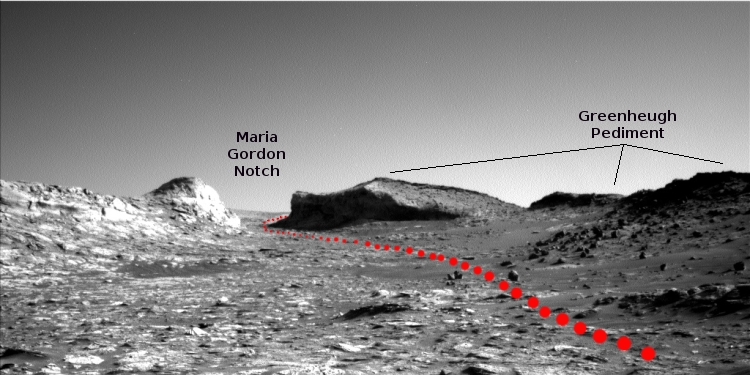

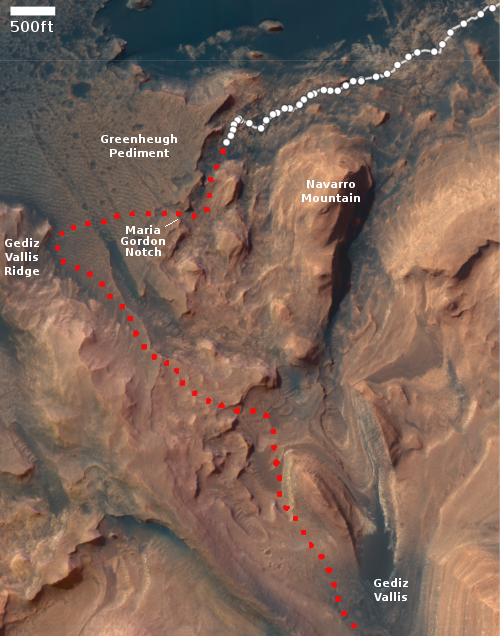

Cool image time! The photo to the right, taken on June 18, 2022 by high resolution camera on the Mars rover Curiosity, provides a close-up of the area indicated by the arrow in the navigation camera image above taken three days earlier.

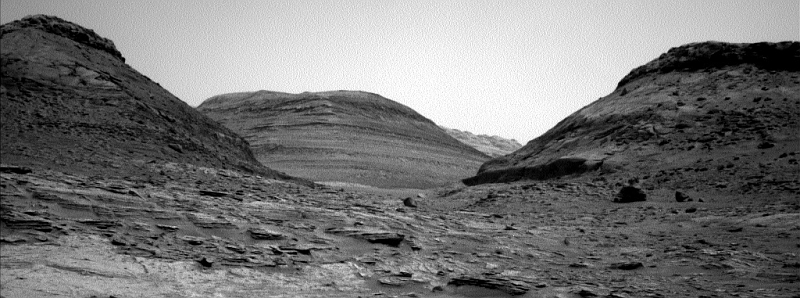

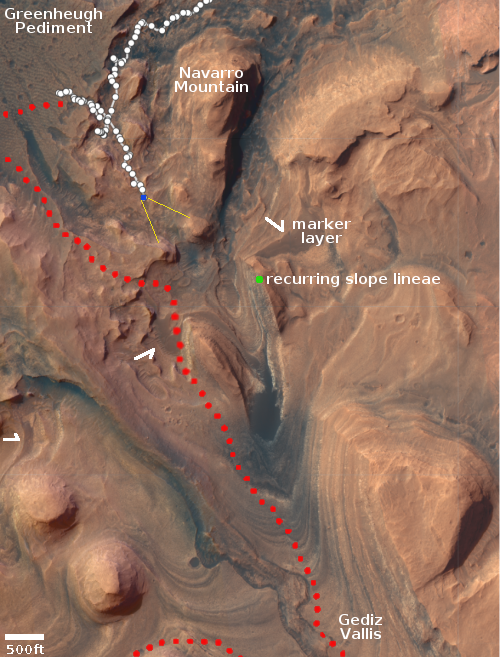

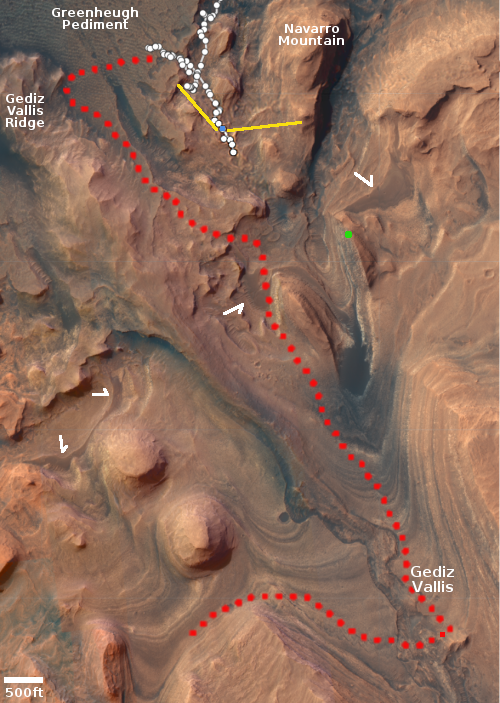

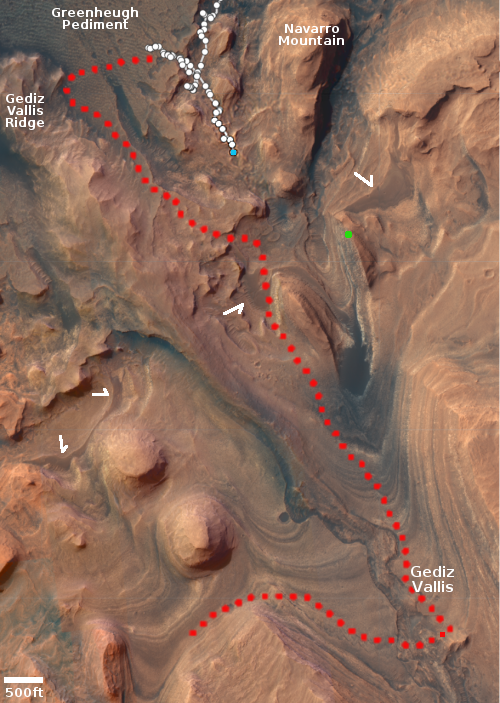

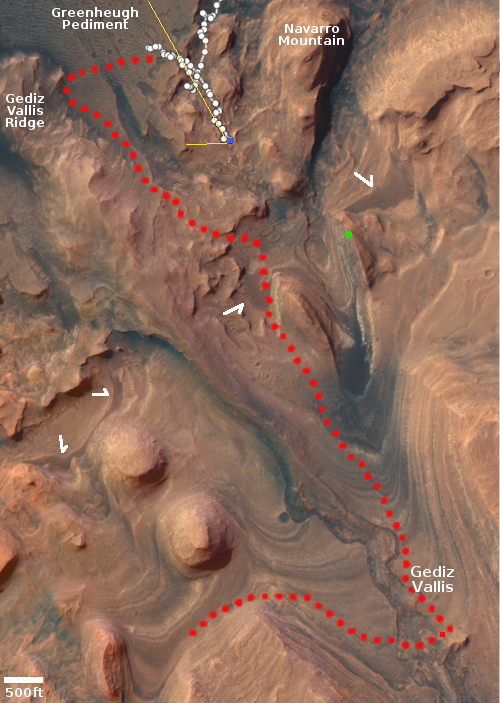

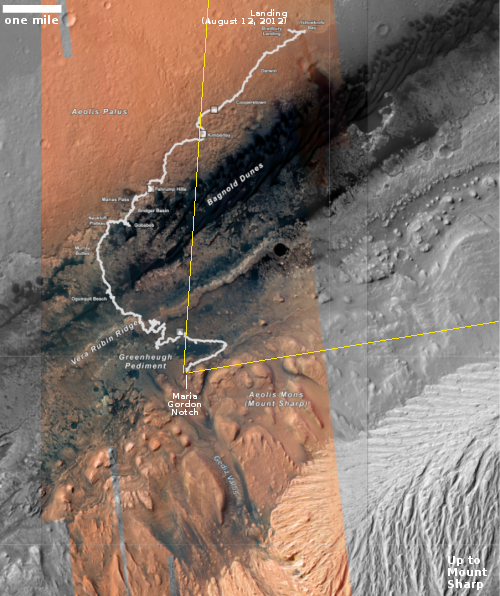

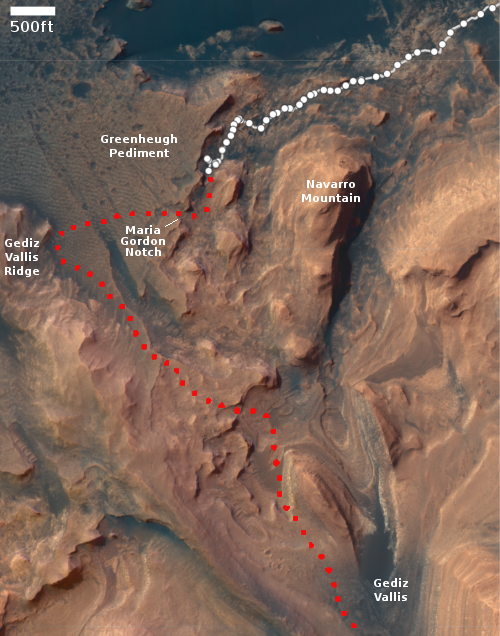

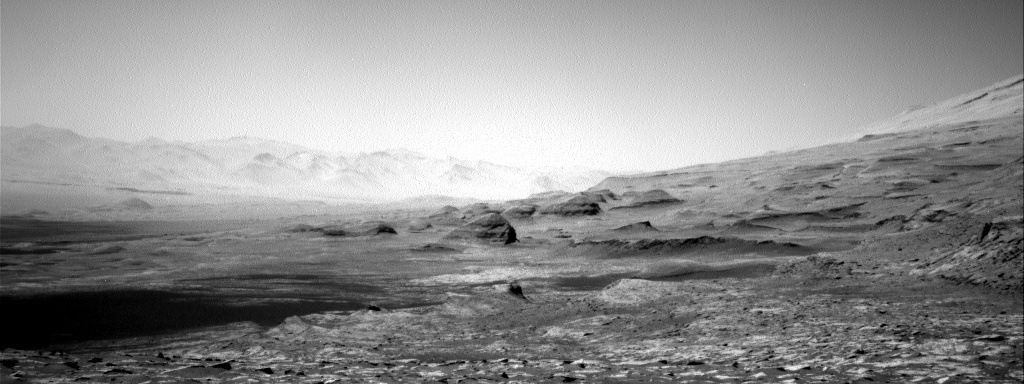

Because the rover had moved uphill slightly during those three days, the close-up can peek over what was the most distant ridge to see farther up Mount Sharp. (For context take a look at the overview map here.) All told, this close-up to the right shows four mountain ridges/ranges. First we have the ridgeline to the right, partly in shadow, which forms the right wall of the saddle that Curiosity appears heading for. Next we can see to the left the top section of the large 1,500 foot high mesa on the other side of the canyon Gediz Vallis. Note its many layers, all of which are going to become a major item of study as Curiosity gets closer.

Third we have a very rough and tumbled ridgeline, formed in a layer the geologists have dubbed the sulfate bearing unit. This layer tends to be very light in color, and more easily eroded. Curiosity is presently beginning to move into this layer as it climbs.

Finally there is the most distant ridge, which is simply the higher reaches of Mount Sharp though not its peak by a long shot.

The dusty winter air is quite evident by the chariscuro effect, causing the more distant ridges to appear more faded.

Note: This will be the first of three cool Martian images today. Stay tuned.

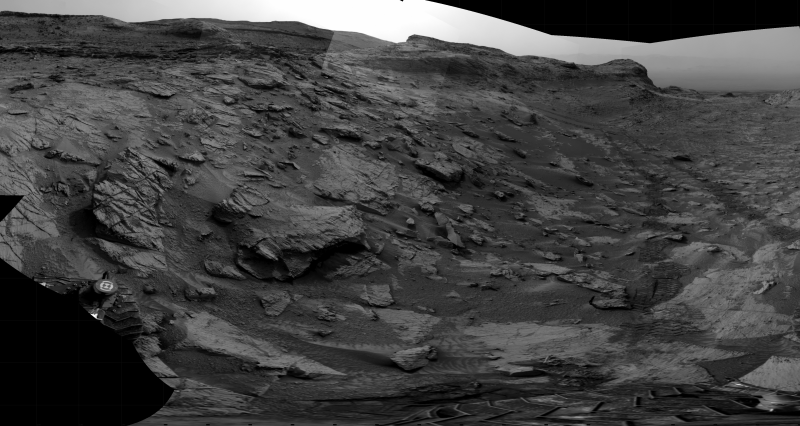

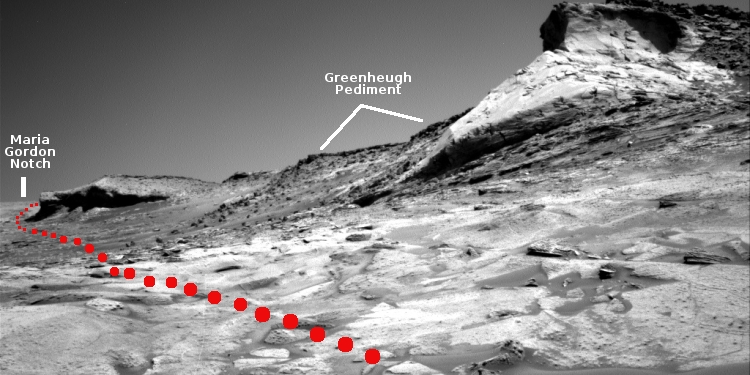

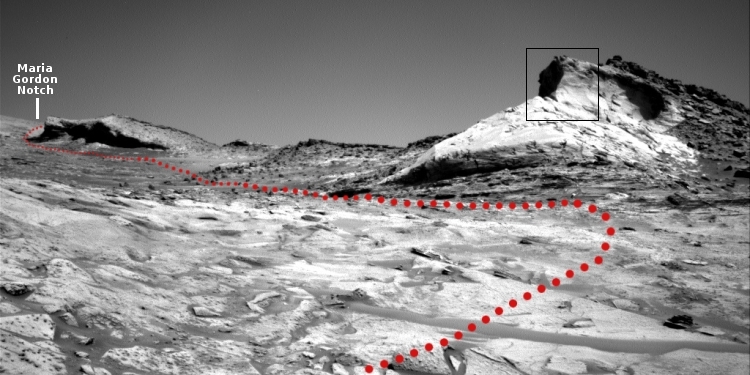

Cool image time! The photo to the right, taken on June 18, 2022 by high resolution camera on the Mars rover Curiosity, provides a close-up of the area indicated by the arrow in the navigation camera image above taken three days earlier.

Because the rover had moved uphill slightly during those three days, the close-up can peek over what was the most distant ridge to see farther up Mount Sharp. (For context take a look at the overview map here.) All told, this close-up to the right shows four mountain ridges/ranges. First we have the ridgeline to the right, partly in shadow, which forms the right wall of the saddle that Curiosity appears heading for. Next we can see to the left the top section of the large 1,500 foot high mesa on the other side of the canyon Gediz Vallis. Note its many layers, all of which are going to become a major item of study as Curiosity gets closer.

Third we have a very rough and tumbled ridgeline, formed in a layer the geologists have dubbed the sulfate bearing unit. This layer tends to be very light in color, and more easily eroded. Curiosity is presently beginning to move into this layer as it climbs.

Finally there is the most distant ridge, which is simply the higher reaches of Mount Sharp though not its peak by a long shot.

The dusty winter air is quite evident by the chariscuro effect, causing the more distant ridges to appear more faded.

Note: This will be the first of three cool Martian images today. Stay tuned.