Firefly delivers its first Blue Ghost lunar lander for final environmental testing

Blue Ghost in clean room

Firefly this week completed the integration of the ten customer payloads onto its first Blue Ghost lunar lander and shipped the lander to JPL in California for final environmental testing before its planned launch before the end of this year.

Following final testing, Firefly’s Blue Ghost will ship to Cape Canaveral, Florida, ahead of its launch on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket scheduled for Q4 2024. Blue Ghost will then begin its transit to the Moon, including approximately a month in Earth orbit and two weeks in lunar orbit. This approach provides ample time to conduct robust health checks on each subsystem and begin payload operations during transit.

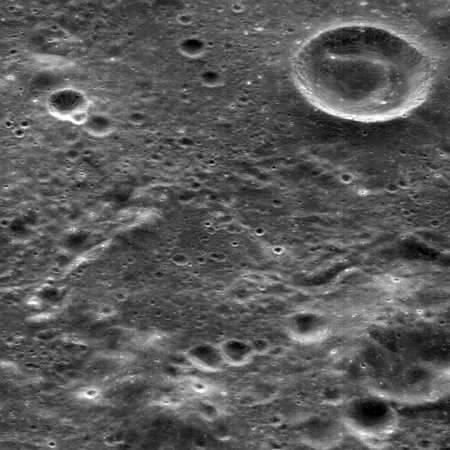

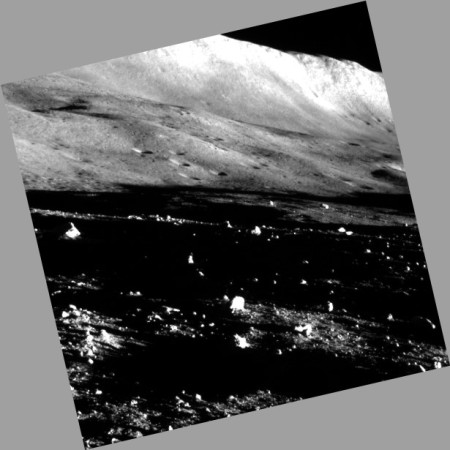

Blue Ghost will then land in Mare Crisium, a basin in the northeast quadrant on the Moon’s near side, before deploying and operating 10 instruments for a lunar day (14 Earth days) and more than 5 hours into the lunar night.

Once launched, Firefly will become the third American company, after Astrobotic and Intuitive Machines, to build a privately owned lunar lander and attempt a lunar landing. Since the other two companies were not entirely successful in their landing attempts, Firefly has the chance to be the first to succeed.

Blue Ghost in clean room

Firefly this week completed the integration of the ten customer payloads onto its first Blue Ghost lunar lander and shipped the lander to JPL in California for final environmental testing before its planned launch before the end of this year.

Following final testing, Firefly’s Blue Ghost will ship to Cape Canaveral, Florida, ahead of its launch on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket scheduled for Q4 2024. Blue Ghost will then begin its transit to the Moon, including approximately a month in Earth orbit and two weeks in lunar orbit. This approach provides ample time to conduct robust health checks on each subsystem and begin payload operations during transit.

Blue Ghost will then land in Mare Crisium, a basin in the northeast quadrant on the Moon’s near side, before deploying and operating 10 instruments for a lunar day (14 Earth days) and more than 5 hours into the lunar night.

Once launched, Firefly will become the third American company, after Astrobotic and Intuitive Machines, to build a privately owned lunar lander and attempt a lunar landing. Since the other two companies were not entirely successful in their landing attempts, Firefly has the chance to be the first to succeed.