Martian swirls and curlicues

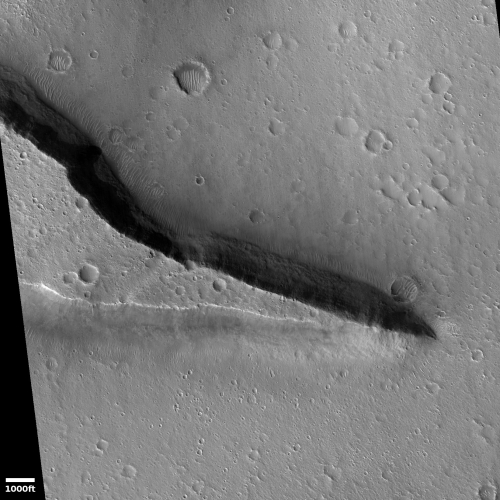

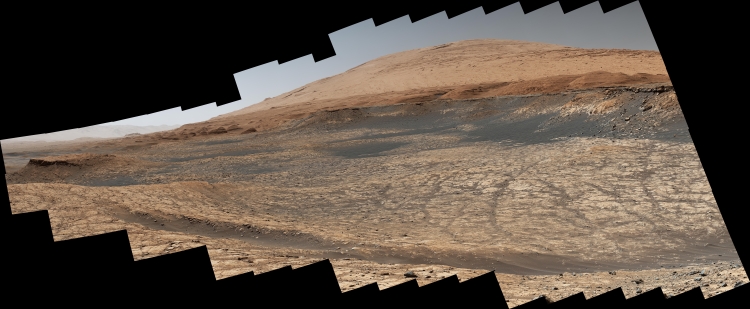

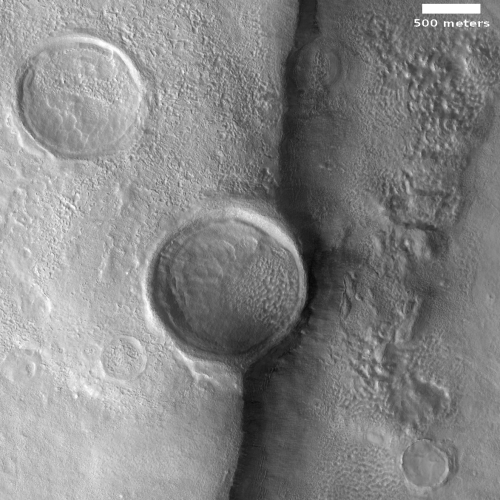

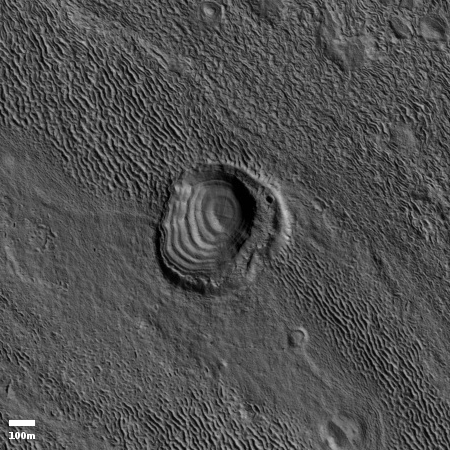

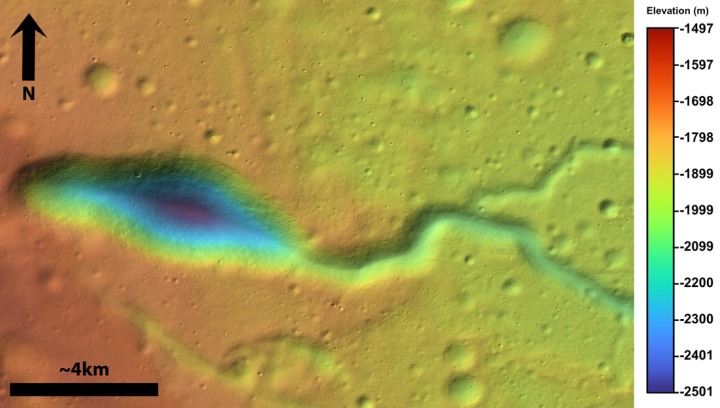

Cool image time! The photo to the right, cropped and reduced to post here, is a great example of how a well known geological process on Earth, glaciers, can form features on Mars that appear most inexplicable.

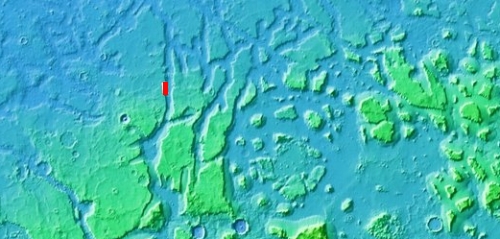

The image was taken on May 13, 2020 and highlights the geology found in a depression, likely an eroded crater, on the northwest flanks of one of Mars’ largest basins, Argyre Planitia, located in the planet’s southern cratered highlands. The basin is thought to have been formed by a giant impact during the Late Heavy Bombardment around 3.9 billion years ago, when the inner terrestrial planets were sweeping up the last remnants of the Sun’s accretion disk, with that process causing the many craters we see on the Moon, Mercury, and Mars

This particular depression is at 41 degrees south latitude, in the mid-latitudes where scientists have found much evidence of buried glaciers. This is likely what we are looking at here. The section I’ve cropped has a dip to the south, which somewhat fits these flow features. If you look at the full image, you will see comparably weird flow features south of this section, flowing downhill in the opposite direction, to the north.

The problem is that not all the features fit the direction of flow, or any flow at all. I suspect we are seeing evidence of the waxing and waning of glaciers over this terrain over many eons. Disentangling that history however is confounding, especially when we are limited to only studying such objects from orbit.

I must also add that this image was labeled by the MRO science team a “terrain sample,” which means it wasn’t specifically requested by any scientist studying this geology. Instead, they needed to take an image to maintain the spacecraft’s camera temperature, and picked this spot for that snapshot. Their choice wasn’t random, but it also wasn’t based on any focused research.

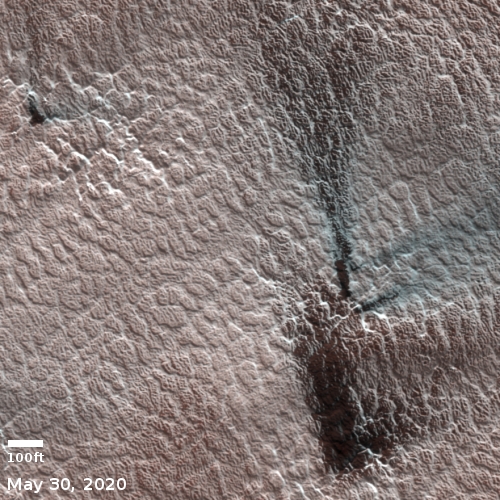

Cool image time! The photo to the right, cropped and reduced to post here, is a great example of how a well known geological process on Earth, glaciers, can form features on Mars that appear most inexplicable.

The image was taken on May 13, 2020 and highlights the geology found in a depression, likely an eroded crater, on the northwest flanks of one of Mars’ largest basins, Argyre Planitia, located in the planet’s southern cratered highlands. The basin is thought to have been formed by a giant impact during the Late Heavy Bombardment around 3.9 billion years ago, when the inner terrestrial planets were sweeping up the last remnants of the Sun’s accretion disk, with that process causing the many craters we see on the Moon, Mercury, and Mars

This particular depression is at 41 degrees south latitude, in the mid-latitudes where scientists have found much evidence of buried glaciers. This is likely what we are looking at here. The section I’ve cropped has a dip to the south, which somewhat fits these flow features. If you look at the full image, you will see comparably weird flow features south of this section, flowing downhill in the opposite direction, to the north.

The problem is that not all the features fit the direction of flow, or any flow at all. I suspect we are seeing evidence of the waxing and waning of glaciers over this terrain over many eons. Disentangling that history however is confounding, especially when we are limited to only studying such objects from orbit.

I must also add that this image was labeled by the MRO science team a “terrain sample,” which means it wasn’t specifically requested by any scientist studying this geology. Instead, they needed to take an image to maintain the spacecraft’s camera temperature, and picked this spot for that snapshot. Their choice wasn’t random, but it also wasn’t based on any focused research.