Perseverance spots its parachute

Click for full resolution. Original images found here and here.

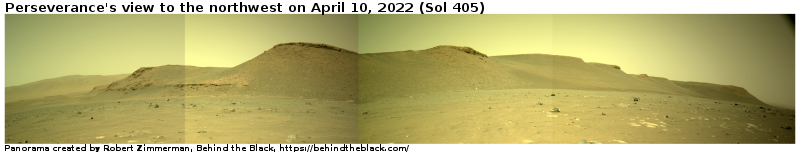

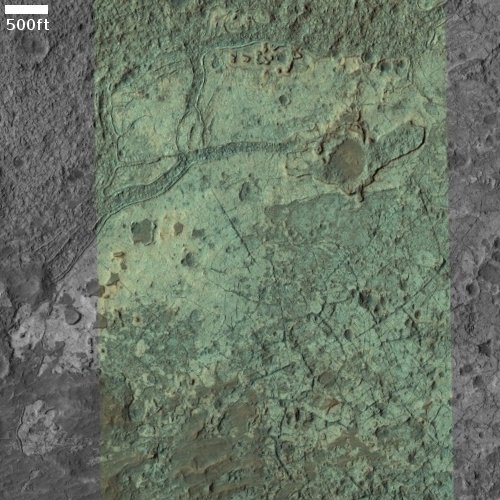

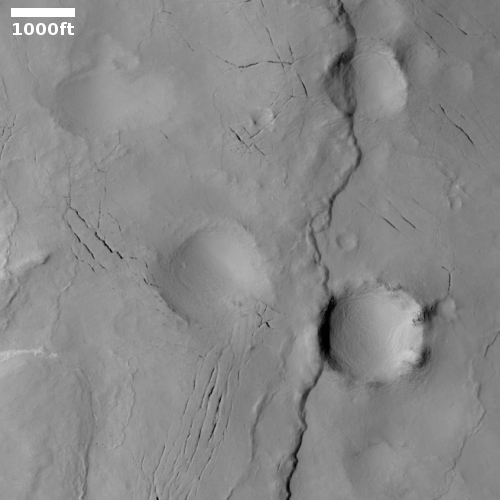

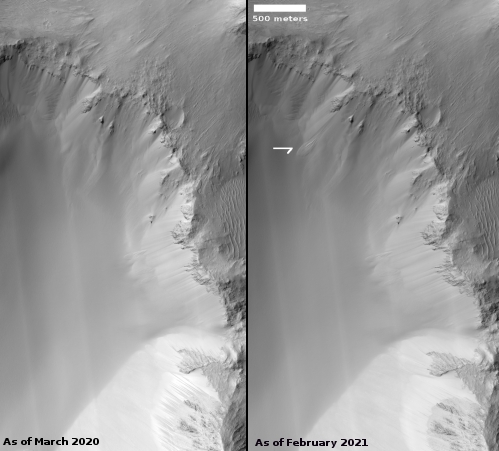

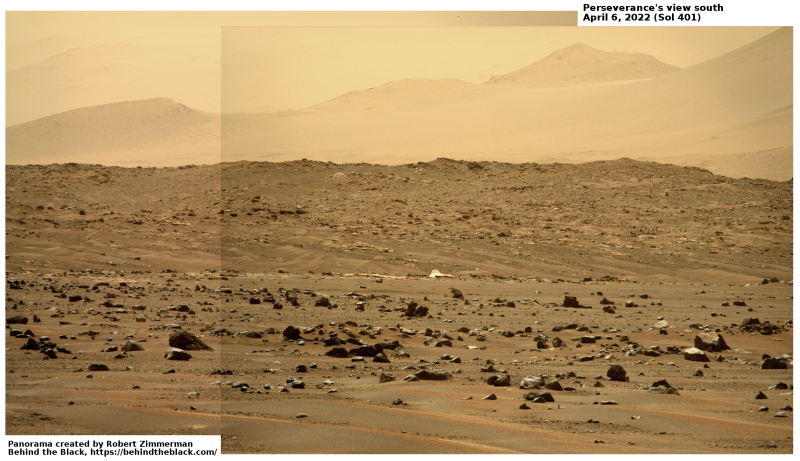

Cool image time! Today the Perseverance science team released two photos taken on April 6th that captured the parachute that the rover had used to land on Mars on February 18, 2021. The enhanced panorama above is from those images. The white feature near the center is the parachute. The mountains in the distance are the southern rim of Jezero Crater, about 40 miles away.

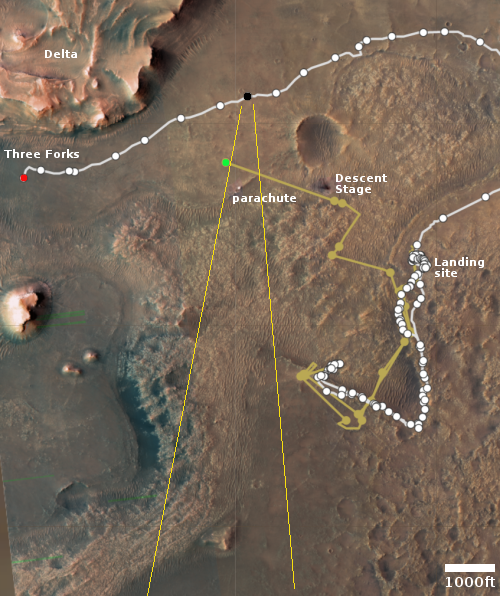

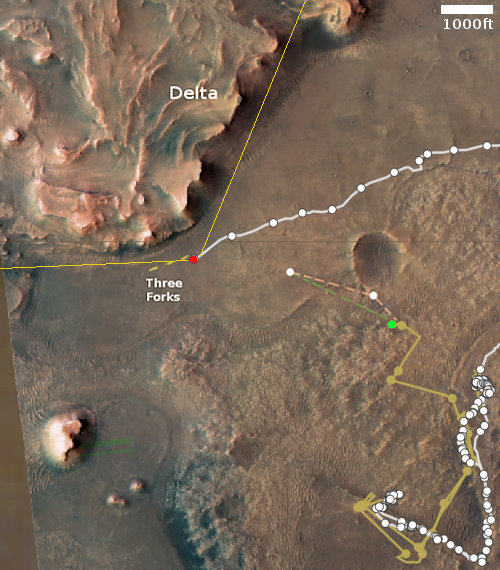

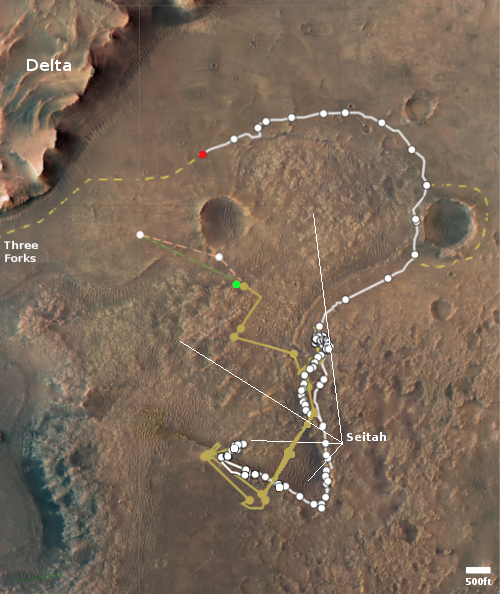

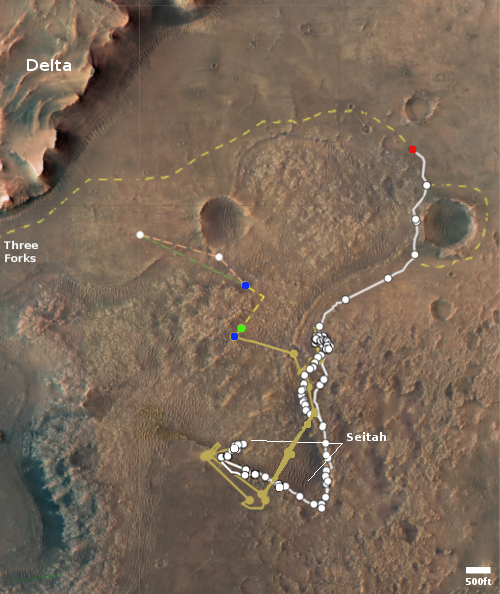

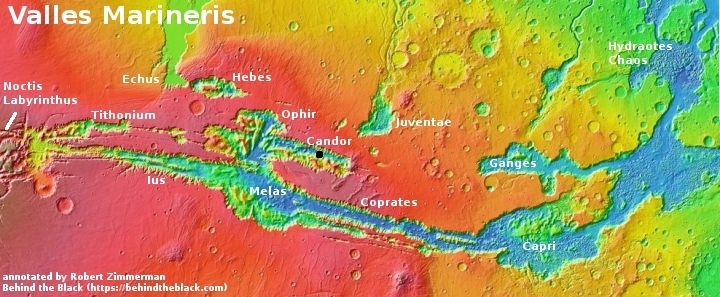

The overview map to the right gives the context. The red dot is Perserverance’s location as of yesterday, on sol 413. The black dot marks its location on April 6th, when it took the pictures. The green dot marks Ingenuity’s present position. The yellow lines indicate the approximate area covered by the panorama.

Ingenuity had not completed its 25th flight until April 8th, two days after these photos were taken, so it isn’t actually just off the edge of these photos, it is beyond the near ridgeline out of sight.

Click for full resolution. Original images found here and here.

Cool image time! Today the Perseverance science team released two photos taken on April 6th that captured the parachute that the rover had used to land on Mars on February 18, 2021. The enhanced panorama above is from those images. The white feature near the center is the parachute. The mountains in the distance are the southern rim of Jezero Crater, about 40 miles away.

The overview map to the right gives the context. The red dot is Perserverance’s location as of yesterday, on sol 413. The black dot marks its location on April 6th, when it took the pictures. The green dot marks Ingenuity’s present position. The yellow lines indicate the approximate area covered by the panorama.

Ingenuity had not completed its 25th flight until April 8th, two days after these photos were taken, so it isn’t actually just off the edge of these photos, it is beyond the near ridgeline out of sight.