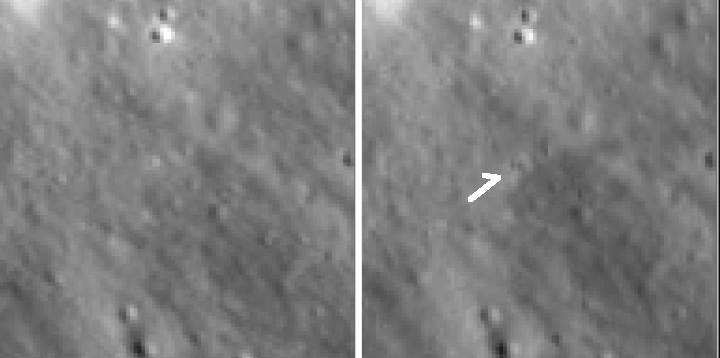

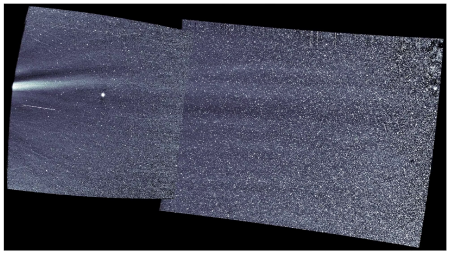

New image of Comet 2I/Borisov

Astronomers have taken a new image of the interstellar comet 2I/Borisov. The photograph to the right is that image, with the Earth placed alongside to show scale.

According to van Dokkum the comet’s tail, shown in the new image, is nearly 100,000 miles long, which is 14 times the size of Earth. “It’s humbling to realize how small Earth is next to this visitor from another solar system,” van Dokkum said.

Laughlin noted that 2l/Borisov is evaporating as it gets closer to Earth, releasing gas and fine dust in its tail. “Astronomers are taking advantage of Borisov’s visit, using telescopes such as Keck to obtain information about the building blocks of planets in systems other than our own,” Laughlin said.

The solid nucleus of the comet is only about a mile wide. As it began reacting to the Sun’s warming effect, the comet has taken on a “ghostly” appearance, the researchers said.

The comet will reach its closest point to the Earth, 190 million miles, in early December.

Astronomers have taken a new image of the interstellar comet 2I/Borisov. The photograph to the right is that image, with the Earth placed alongside to show scale.

According to van Dokkum the comet’s tail, shown in the new image, is nearly 100,000 miles long, which is 14 times the size of Earth. “It’s humbling to realize how small Earth is next to this visitor from another solar system,” van Dokkum said.

Laughlin noted that 2l/Borisov is evaporating as it gets closer to Earth, releasing gas and fine dust in its tail. “Astronomers are taking advantage of Borisov’s visit, using telescopes such as Keck to obtain information about the building blocks of planets in systems other than our own,” Laughlin said.

The solid nucleus of the comet is only about a mile wide. As it began reacting to the Sun’s warming effect, the comet has taken on a “ghostly” appearance, the researchers said.

The comet will reach its closest point to the Earth, 190 million miles, in early December.