One last look at a Martian mountaintop

For the original images go here and here.

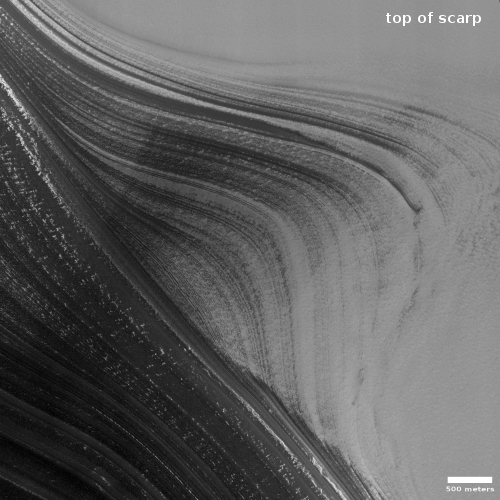

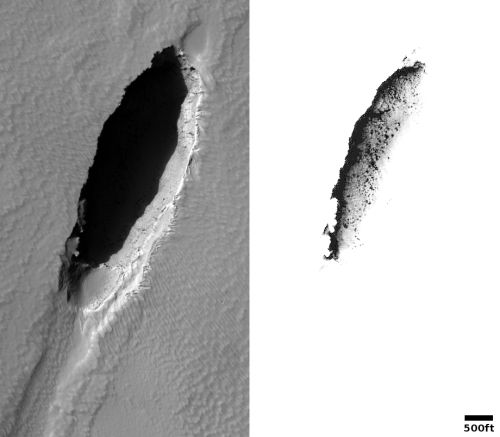

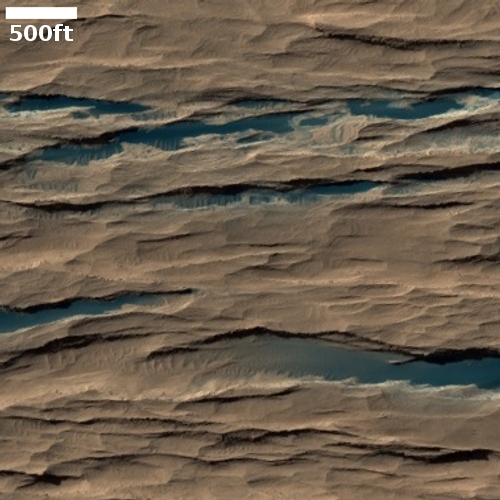

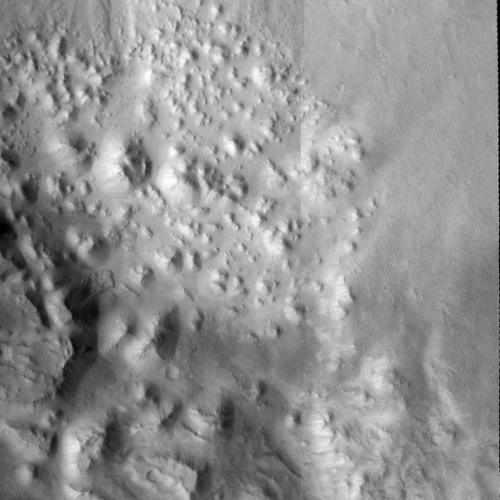

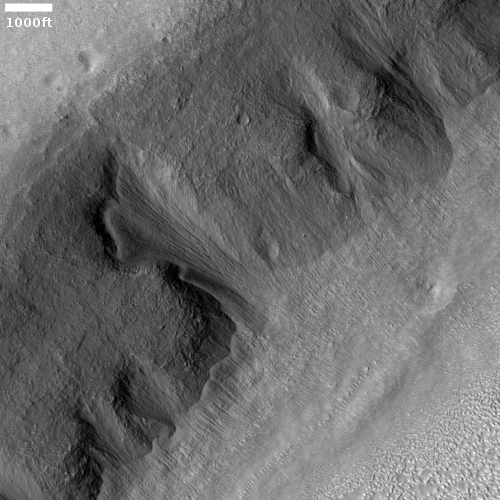

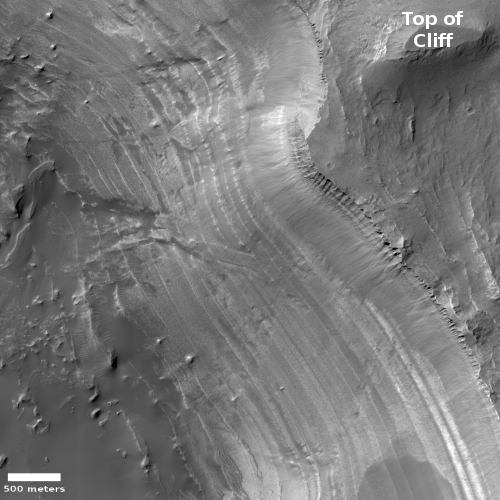

The image above is a mosaic made from two Curiosity navigation photos taken on October 23, 2021 and combined, cropped, and reduced to post here. It shows the top 30 feet or so of Siccar Point, the spectacular outcrop that I have featured several times previously.

Curiosity has now traveled past this outcrop, so that this view above is no longer visible to the rover. I post it now as a farewell image of what I think is the most breath-taking feature yet seen by any planetary lander — manned or unmanned — since the first set down on the Moon in the mid-1960s. It also illustrates with great clarity the alien nature of Mars. Those delicate overhanging rocks would not be possible on Earth, with a gravity about two and a half times heavier than Mars.

Note too that I have not enhanced the contrast or brightness. I think the twilight light here actually gives us a sense of the real brightness of a clear Martian day. Because the Sun is much farther away, even at high noon it provides much less illumination than on Earth. A bright day on Mars to our Earth-adapted eyes will always feel like dusk.

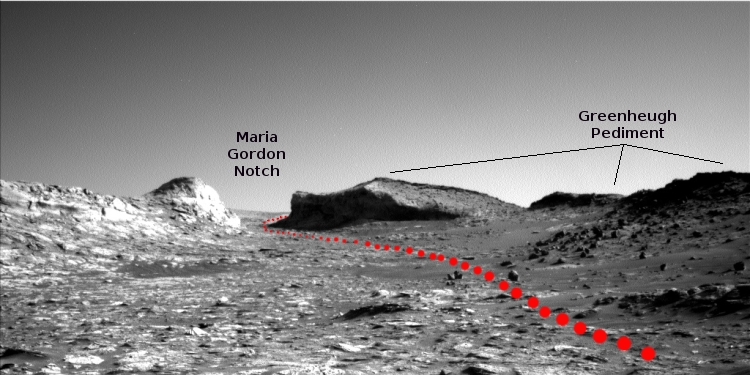

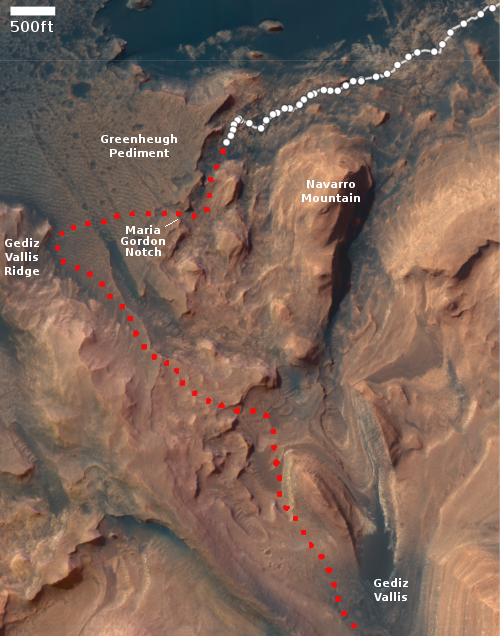

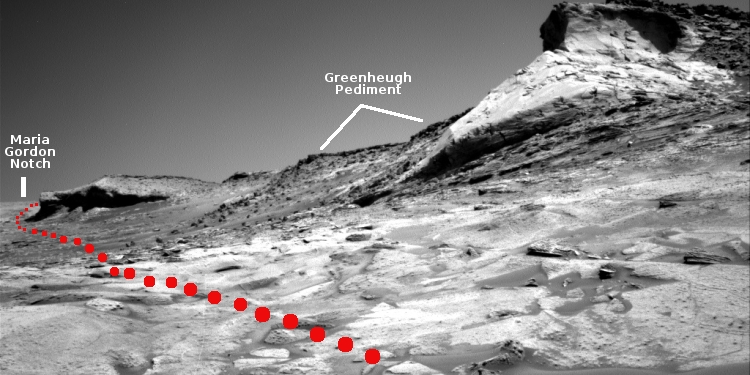

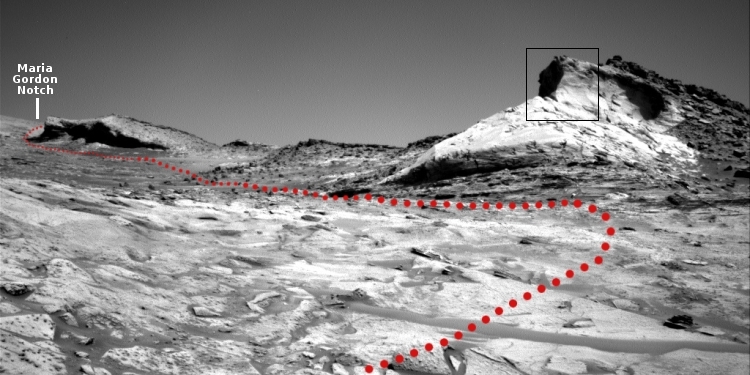

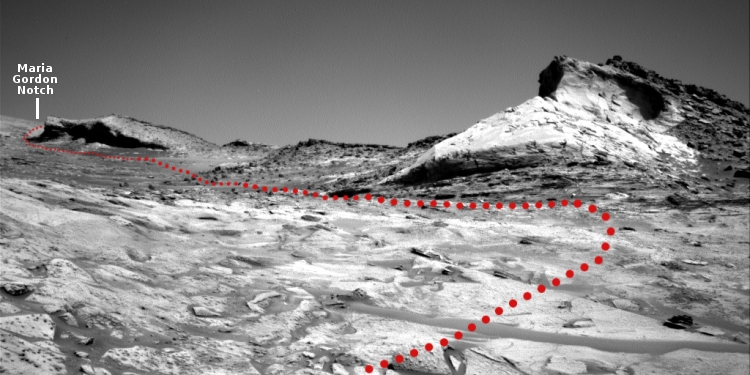

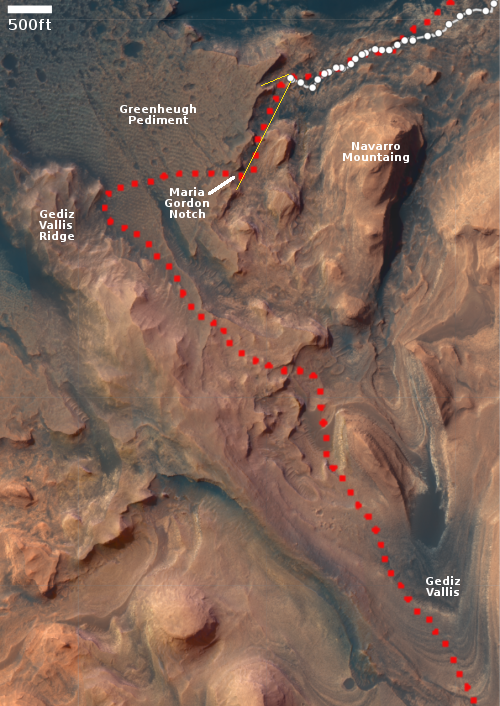

Meanwhile the science team is quickly pushing the rover south, to get…

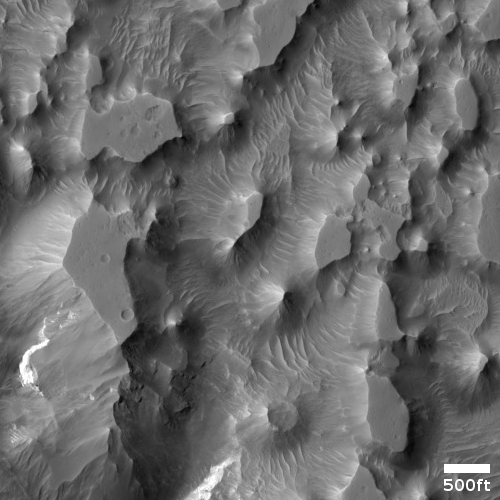

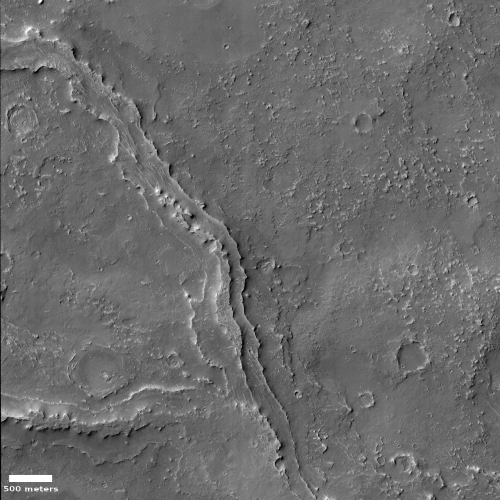

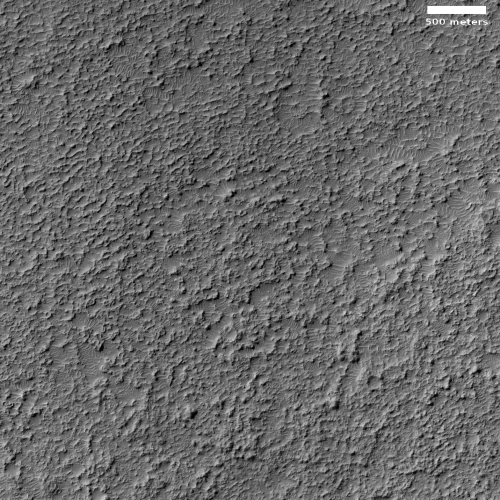

…closer to the area we are targeting for our next drill campaign. This drive should leave us with bedrock in the workspace for additional contact science on the weekend. This terrain continues to be very challenging, with large boulders, sharp rocks that are wheel hazards, and sand ripples, like the terrain shown in the image. These drives take a while to plan to make sure we are avoiding all the hazards while getting to where science wants to go. Our paths end up looking a little “drunk” as we weave our way around obstacles.

For the original images go here and here.

The image above is a mosaic made from two Curiosity navigation photos taken on October 23, 2021 and combined, cropped, and reduced to post here. It shows the top 30 feet or so of Siccar Point, the spectacular outcrop that I have featured several times previously.

Curiosity has now traveled past this outcrop, so that this view above is no longer visible to the rover. I post it now as a farewell image of what I think is the most breath-taking feature yet seen by any planetary lander — manned or unmanned — since the first set down on the Moon in the mid-1960s. It also illustrates with great clarity the alien nature of Mars. Those delicate overhanging rocks would not be possible on Earth, with a gravity about two and a half times heavier than Mars.

Note too that I have not enhanced the contrast or brightness. I think the twilight light here actually gives us a sense of the real brightness of a clear Martian day. Because the Sun is much farther away, even at high noon it provides much less illumination than on Earth. A bright day on Mars to our Earth-adapted eyes will always feel like dusk.

Meanwhile the science team is quickly pushing the rover south, to get…

…closer to the area we are targeting for our next drill campaign. This drive should leave us with bedrock in the workspace for additional contact science on the weekend. This terrain continues to be very challenging, with large boulders, sharp rocks that are wheel hazards, and sand ripples, like the terrain shown in the image. These drives take a while to plan to make sure we are avoiding all the hazards while getting to where science wants to go. Our paths end up looking a little “drunk” as we weave our way around obstacles.