NASA announces mission to Titan

NASA today announced that it has approved a new mission to Titan, called Dragonfly, that will be a rotorcraft able to fly from place to place.

Dragonfly will launch in 2026 as part of NASA’s New Frontiers program, and is expected to arrive at Titan in 2034. ‘Dragonfly is a bold, game-changing way to explore the solar system,’ said APL Director Ralph Semmel. ‘This mission is a visionary combination of creativity and technical risk-taking that will help us unravel some of the most critical mysteries of the universe — including, possibly, the keys to our origins.’

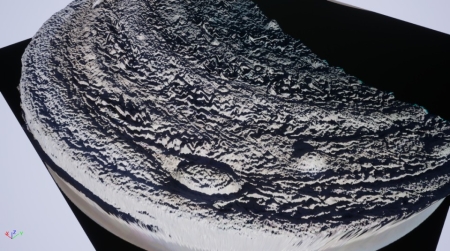

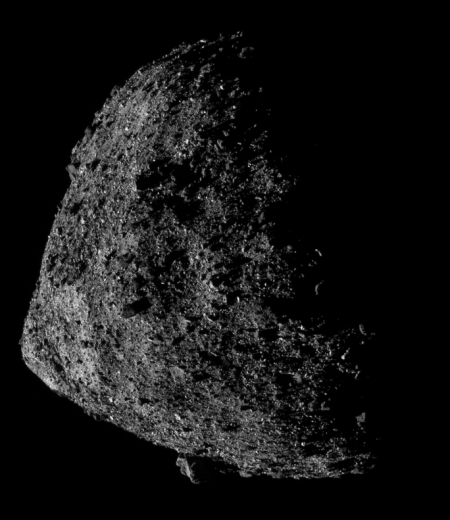

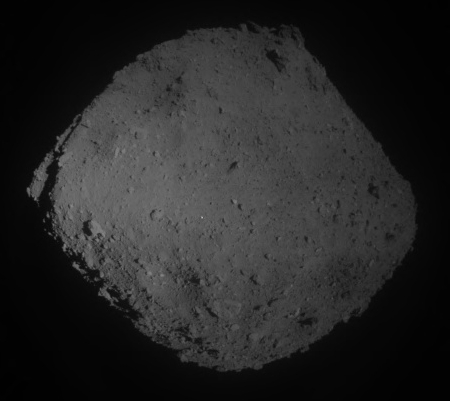

Initially, Dragonfly will carry out a 2.7-year mission to explore different sites across Titan, including dunes and impact craters. Observations from the Cassini mission indicate these areas once held liquid water and complex organic materials. The dual quadcopter will sample these organic surface materials and measure their composition in effort to characterize the large moon’s habitability.

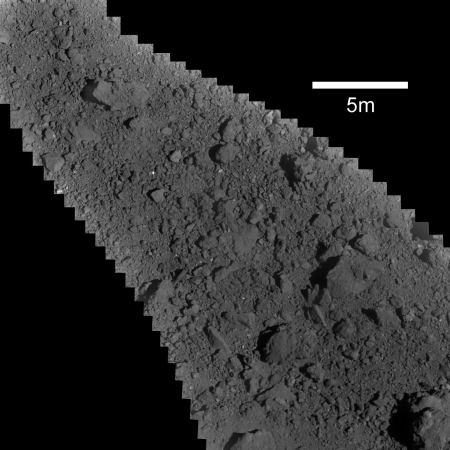

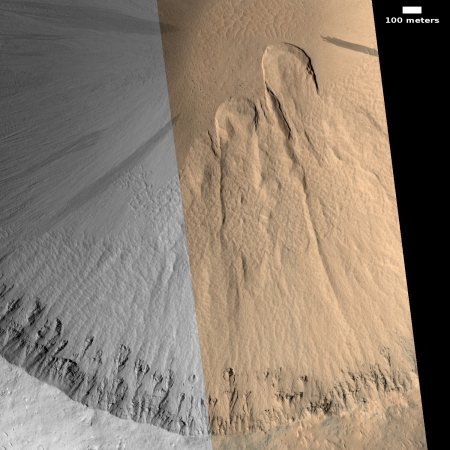

Dragonfly will first touchdown in an equatorial area known as the ‘Shangri-La’ dune fields, which have been compared to the Namibian dunes in southern Africa.

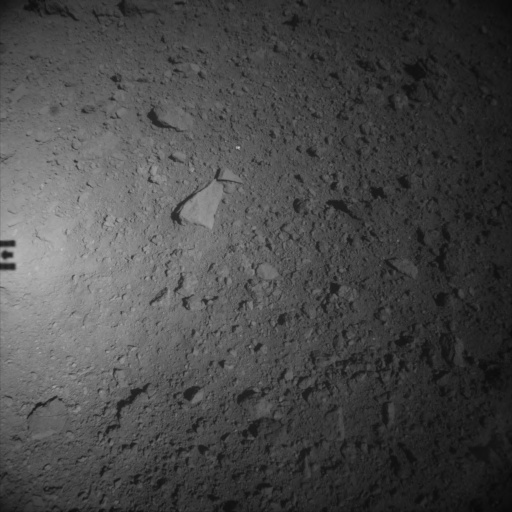

It will then complete ‘leapfrog’ flights of around 5 miles (8km) each to hop to other areas, stopping to take samples from each site.

I hate to throw cold water on this magnificent and ambitious mission, but I will not be at all surprised if it ends up costing more than expected and ends up getting delayed. NASA’s track record in the past decade with big projects on the cutting edge, as this appears to be, has been abysmal. Worse, I have seen little at NASA to make me thing any of this has changed enough to ease my mind for the next decade.

I hope I am wrong, because the concept is wonderful, and the target, Titan, is a critical solar system location that must be explored.

NASA today announced that it has approved a new mission to Titan, called Dragonfly, that will be a rotorcraft able to fly from place to place.

Dragonfly will launch in 2026 as part of NASA’s New Frontiers program, and is expected to arrive at Titan in 2034. ‘Dragonfly is a bold, game-changing way to explore the solar system,’ said APL Director Ralph Semmel. ‘This mission is a visionary combination of creativity and technical risk-taking that will help us unravel some of the most critical mysteries of the universe — including, possibly, the keys to our origins.’

Initially, Dragonfly will carry out a 2.7-year mission to explore different sites across Titan, including dunes and impact craters. Observations from the Cassini mission indicate these areas once held liquid water and complex organic materials. The dual quadcopter will sample these organic surface materials and measure their composition in effort to characterize the large moon’s habitability.

Dragonfly will first touchdown in an equatorial area known as the ‘Shangri-La’ dune fields, which have been compared to the Namibian dunes in southern Africa.

It will then complete ‘leapfrog’ flights of around 5 miles (8km) each to hop to other areas, stopping to take samples from each site.

I hate to throw cold water on this magnificent and ambitious mission, but I will not be at all surprised if it ends up costing more than expected and ends up getting delayed. NASA’s track record in the past decade with big projects on the cutting edge, as this appears to be, has been abysmal. Worse, I have seen little at NASA to make me thing any of this has changed enough to ease my mind for the next decade.

I hope I am wrong, because the concept is wonderful, and the target, Titan, is a critical solar system location that must be explored.