OSIRIS-REx to make one last observation of Bennu before heading back to Earth

The OSIRIS-REx science team has figured out a way to make one last observation of Bennu and the Nightingale sample return site before heading back to Earth on May 10th.

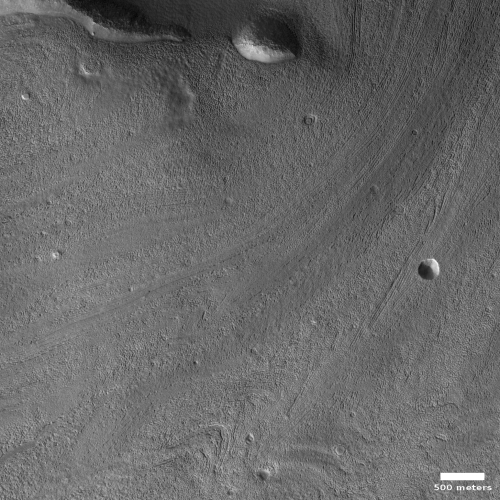

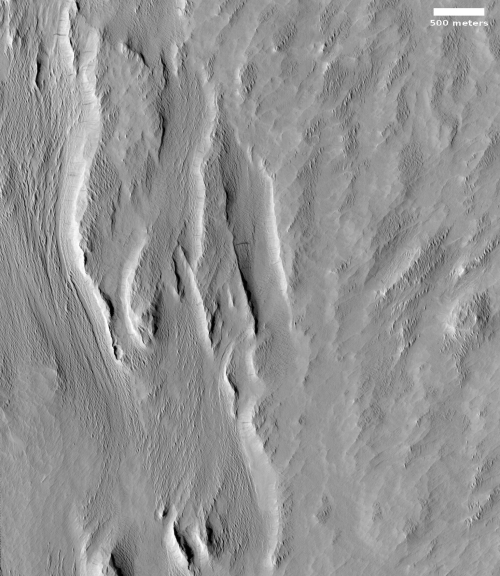

This activity was not part of the original mission schedule, but the team is studying the feasibility of a final observation run of the asteroid to potentially learn how the spacecraft’s contact with Bennu’s surface altered the sample site. If feasible, the flyby will take place in early April and will observe the sample site, named Nightingale, from a distance of approximately 2 miles (3.2 kilometers). Bennu’s surface was considerably disturbed after the Touch-and-Go (TAG) sample collection event, with the collector head sinking 1.6 feet (48.8 centimeters) into the asteroid’s surface. The spacecraft’s thrusters also disturbed a substantial amount of surface material during the back-away burn.

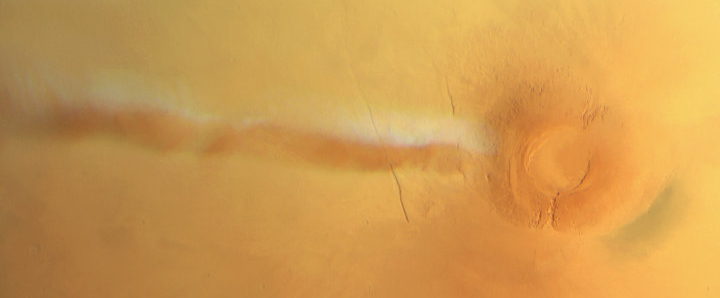

The mission is planning a single flyby, mimicking one of the observation sequences conducted during the mission’s Detailed Survey phase in 2019. OSIRIS-REx would image Bennu for a full rotation to obtain high-resolution images of the asteroid’s northern and southern hemispheres and equatorial region. The team would then compare these new images with the previous high-resolution imagery of Bennu obtained during 2019.

Getting at look at Nightingale post-sample-grab is critical to better understanding the nature of the asteroid. Knowing how much changed from that contact will tell scientists a lot about the density, interior, and surface of this rubble-pile asteroid.

This last flyby will also give them the chance to assess the spacecraft’s equipment following the touch-and-go sample grab. They want to know if everything still works as designed in order to plan any post-Bennu missions, including the possibility that OSIRIS-REx will rendezvous with the asteroid Apophis in ’29, shortly after the asteroid makes its next close flyby of Earth.

The OSIRIS-REx science team has figured out a way to make one last observation of Bennu and the Nightingale sample return site before heading back to Earth on May 10th.

This activity was not part of the original mission schedule, but the team is studying the feasibility of a final observation run of the asteroid to potentially learn how the spacecraft’s contact with Bennu’s surface altered the sample site. If feasible, the flyby will take place in early April and will observe the sample site, named Nightingale, from a distance of approximately 2 miles (3.2 kilometers). Bennu’s surface was considerably disturbed after the Touch-and-Go (TAG) sample collection event, with the collector head sinking 1.6 feet (48.8 centimeters) into the asteroid’s surface. The spacecraft’s thrusters also disturbed a substantial amount of surface material during the back-away burn.

The mission is planning a single flyby, mimicking one of the observation sequences conducted during the mission’s Detailed Survey phase in 2019. OSIRIS-REx would image Bennu for a full rotation to obtain high-resolution images of the asteroid’s northern and southern hemispheres and equatorial region. The team would then compare these new images with the previous high-resolution imagery of Bennu obtained during 2019.

Getting at look at Nightingale post-sample-grab is critical to better understanding the nature of the asteroid. Knowing how much changed from that contact will tell scientists a lot about the density, interior, and surface of this rubble-pile asteroid.

This last flyby will also give them the chance to assess the spacecraft’s equipment following the touch-and-go sample grab. They want to know if everything still works as designed in order to plan any post-Bennu missions, including the possibility that OSIRIS-REx will rendezvous with the asteroid Apophis in ’29, shortly after the asteroid makes its next close flyby of Earth.