NASA in contact with China to get the orbital data of its Tianwen-1 Mars Orbiter

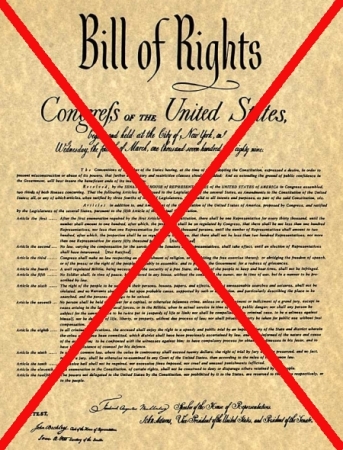

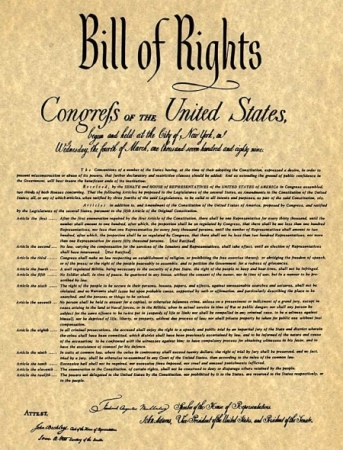

Though by law NASA and the scientists cannot exchange data or communications with China due to security concerns, NASA and Chinese officials did exchange communications recently in order to coordinate the orbits of their orbiters presently circling Mars.

Jurczyk noted that NASA’s knowledge of China’s space program is largely limited to publicly available information because of restrictions placed by federal law on its interactions with Chinese organizations. Those restrictions do allow NASA to engage with China if approved by Congress. “Most recently, we had an exchange with them on them providing their orbital data, their ephemeris data, for their Tianwen-1 Mars orbiting mission, so we could do conjunction analysis around Mars with the orbiters,” he said.

In a brief statement to SpaceNews late March 29, NASA confirmed it exchanged information with the China National Space Administration (CNSA), as well as other space agencies that operate spacecraft at Mars. “To assure the safety of our respective missions, NASA is coordinating with the UAE, European Space Agency, Indian Space Research Organisation and the China National Space Administration, all of which have spacecraft in orbit around Mars, to exchange information on our respective Mars missions to ensure the safety of our respective spacecraft,” the agency said. “This limited exchange of information is consistent with customary good practices used to ensure effective communication among satellite operators and spacecraft safety in orbit.”

Such limited communications are actually permitted under the law that Congress passed, as long as they do not involve any exchange of technical information. There has been a push, however, in the planetary community for years to increase direct communications with China, allowing the transfer of all kinds of information, both scientific and technical. Until the law gets changed none of this should happen.

Of course, what matters laws these days? I will not be surprised if the Biden administration, rather than demanding a change in the law, instead begins expanded communications between NASA and China, in complete and utter contempt for the law, with no one objecting.

Though by law NASA and the scientists cannot exchange data or communications with China due to security concerns, NASA and Chinese officials did exchange communications recently in order to coordinate the orbits of their orbiters presently circling Mars.

Jurczyk noted that NASA’s knowledge of China’s space program is largely limited to publicly available information because of restrictions placed by federal law on its interactions with Chinese organizations. Those restrictions do allow NASA to engage with China if approved by Congress. “Most recently, we had an exchange with them on them providing their orbital data, their ephemeris data, for their Tianwen-1 Mars orbiting mission, so we could do conjunction analysis around Mars with the orbiters,” he said.

In a brief statement to SpaceNews late March 29, NASA confirmed it exchanged information with the China National Space Administration (CNSA), as well as other space agencies that operate spacecraft at Mars. “To assure the safety of our respective missions, NASA is coordinating with the UAE, European Space Agency, Indian Space Research Organisation and the China National Space Administration, all of which have spacecraft in orbit around Mars, to exchange information on our respective Mars missions to ensure the safety of our respective spacecraft,” the agency said. “This limited exchange of information is consistent with customary good practices used to ensure effective communication among satellite operators and spacecraft safety in orbit.”

Such limited communications are actually permitted under the law that Congress passed, as long as they do not involve any exchange of technical information. There has been a push, however, in the planetary community for years to increase direct communications with China, allowing the transfer of all kinds of information, both scientific and technical. Until the law gets changed none of this should happen.

Of course, what matters laws these days? I will not be surprised if the Biden administration, rather than demanding a change in the law, instead begins expanded communications between NASA and China, in complete and utter contempt for the law, with no one objecting.