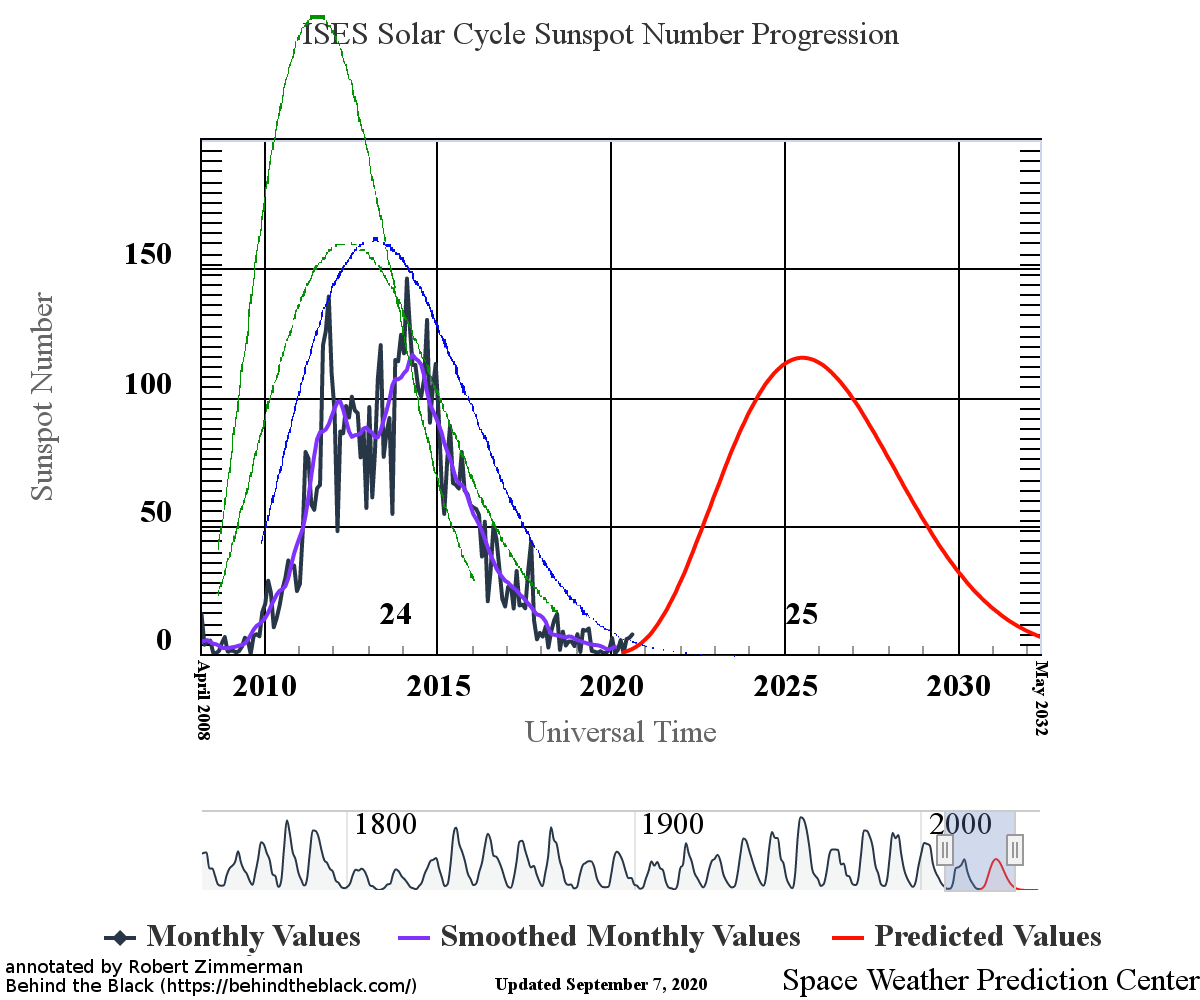

Scientists predict solar maximum to arrive one year early

The scientists whose prediction of a more active upcoming solar maximum that has so far turned out more accurate than the consensus prediction have now updated their prediction, lowering it somewhat but also predicting the maximum will occur one year early, in 2024 instead of 2025.

The team’s finalized forecast for the current cycle expects it to peak in late 2024, one year earlier than NASA and NOAA had predicted. The cycle, the team thinks, will reach about 185 monthly sunspots during its maximum and thus be somewhat milder than what the team originally forecasted. This peak intensity will place this cycle at about the average compared to the historical record.

In other words, now that we are about halfway to maximum, they have concluded that while NOAA’s prediction was too low, their prediction was too high. They have now adjusted their expectations to be closer to what they now think will happen.

A short solar cycle however has historically corresponded to much higher sunspot activity. If this new prediction is correct (a short cycle with a mild maximum), it will mean that the Sun is still behaving in ways that the solar science community does not understand, or can predict.

The scientists whose prediction of a more active upcoming solar maximum that has so far turned out more accurate than the consensus prediction have now updated their prediction, lowering it somewhat but also predicting the maximum will occur one year early, in 2024 instead of 2025.

The team’s finalized forecast for the current cycle expects it to peak in late 2024, one year earlier than NASA and NOAA had predicted. The cycle, the team thinks, will reach about 185 monthly sunspots during its maximum and thus be somewhat milder than what the team originally forecasted. This peak intensity will place this cycle at about the average compared to the historical record.

In other words, now that we are about halfway to maximum, they have concluded that while NOAA’s prediction was too low, their prediction was too high. They have now adjusted their expectations to be closer to what they now think will happen.

A short solar cycle however has historically corresponded to much higher sunspot activity. If this new prediction is correct (a short cycle with a mild maximum), it will mean that the Sun is still behaving in ways that the solar science community does not understand, or can predict.