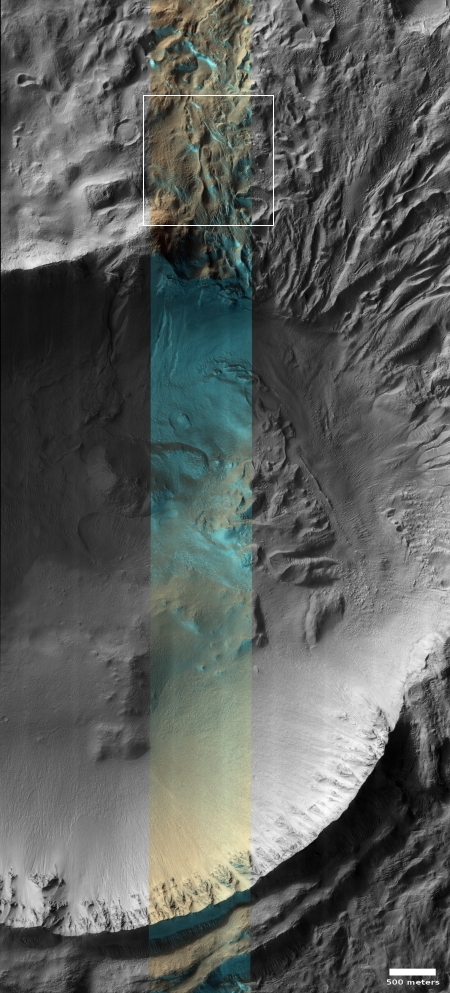

Click for full image.

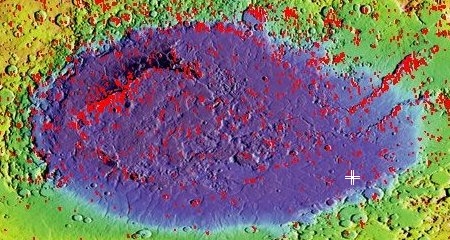

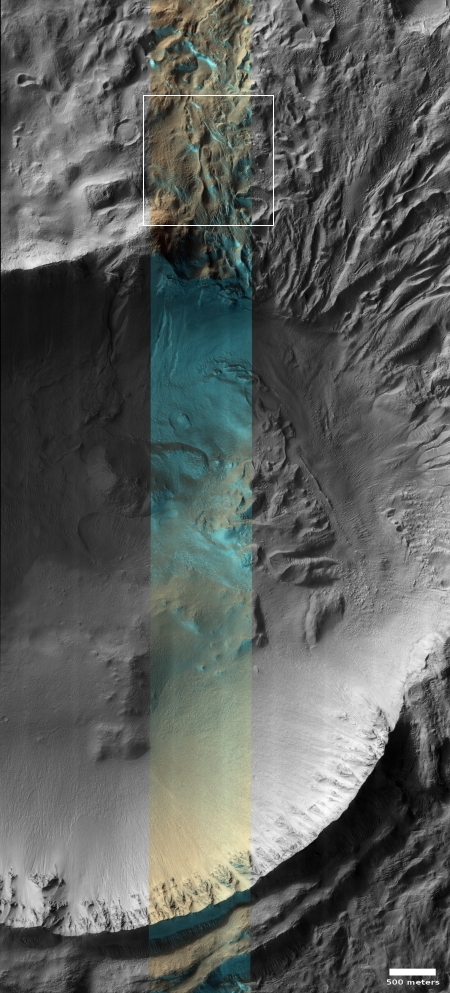

Cool image time! The photo on the right, rotated, cropped, and reduced to post here, was taken by the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter on November 30, 2019. Located just east of Hellas Basin in southern mid-latitudes, the color strip shows dry ice frost both in the crater as well as on the ridgelines to the north. As noted in the caption, written by Candy Hansen of the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona,

When we acquired this image, it was [winter in the southern hemisphere] on Mars, but signs of spring are already starting to appear at latitudes not far from the equator. This image of Penticton Crater, taken at latitude 38 degrees south, shows streamers of seasonal carbon dioxide ice (dry ice) only remaining in places in the terrain that are still partially in the shade.

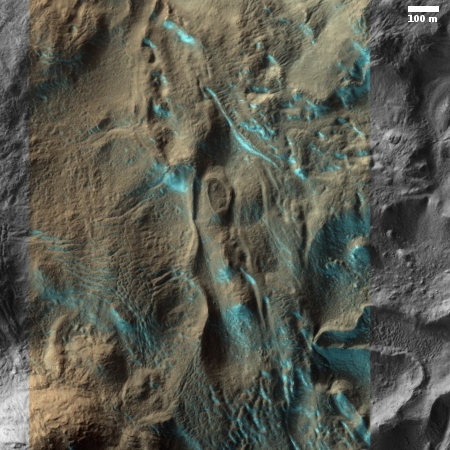

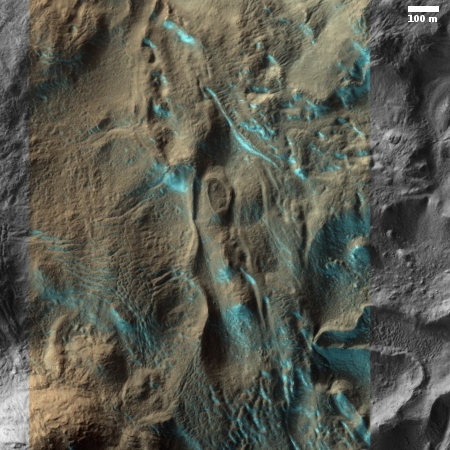

The turquoise-colored frost (enhanced color) is protected from the sun in shadowed dips in the ground while the sunlit surface nearby is already frost-free.

Note for example how the frost disappears in the southern half of the crater floor, the part exposed to sunlight.

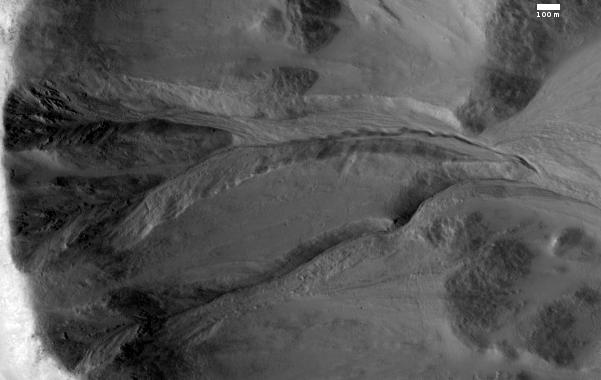

What immediately struck me however were the underlying features. The entire northeast quadrant of the crater’s rim appears to have been breached by some sort of catastrophic flow, as if there had been a glacial lake inside the crater that at some point smashed through suddenly, wiping that part of the rim out as it ripped its way through.

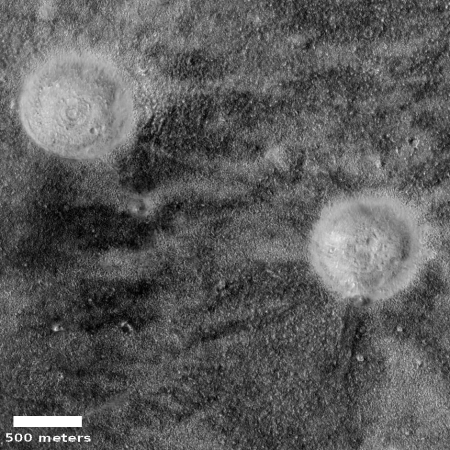

To the right is a full resolution inset, indicated by the white box above, of the dry ice frost on the outside of the crater. I find myself however drawn more to the underlying features, which once again have a chaotic aspect suggesting a sudden violent event, coming from the south and moving north.

I have no idea if my visceral conclusions here have any validity. At this latitude, 38 degrees, scientists have found a lot of buried inactive glaciers of ice, so I could be right. Or not. Your guess is as good as mine.