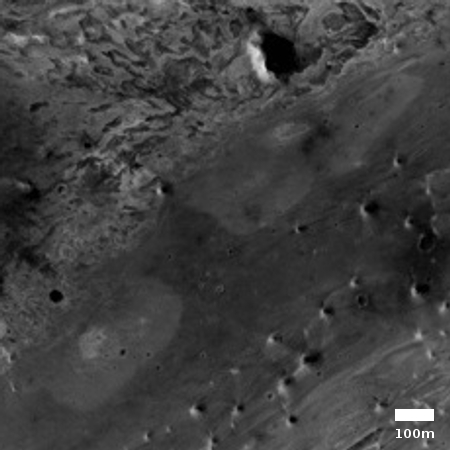

Rock droplets hitting a Martian plain

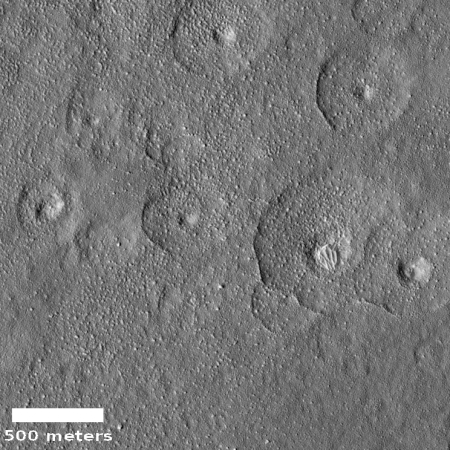

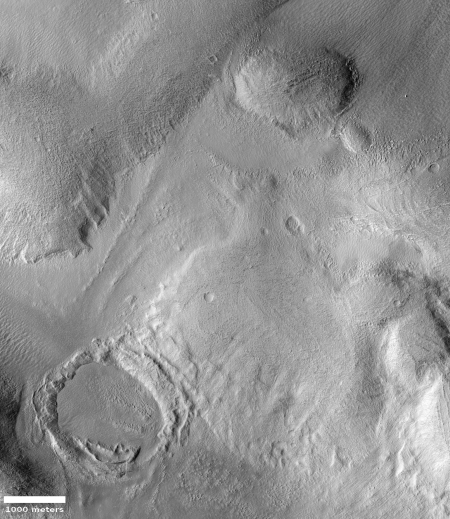

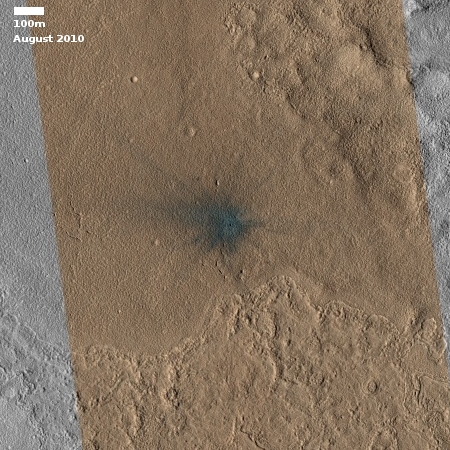

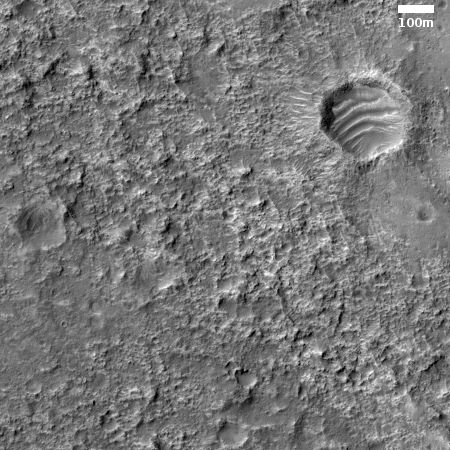

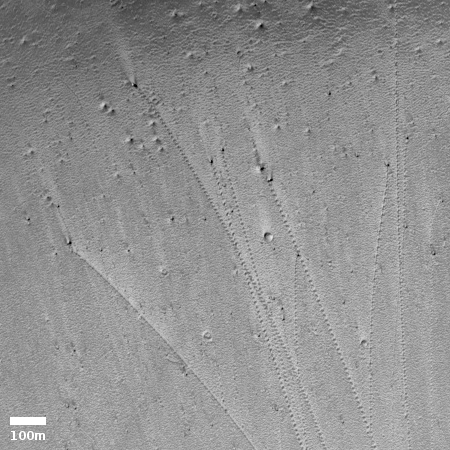

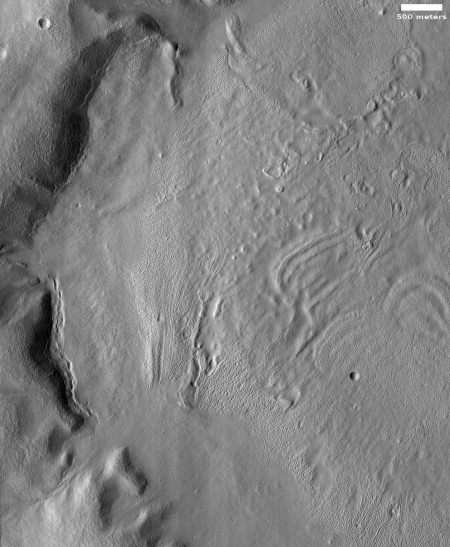

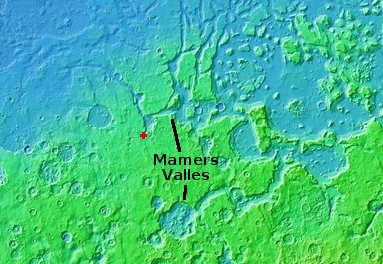

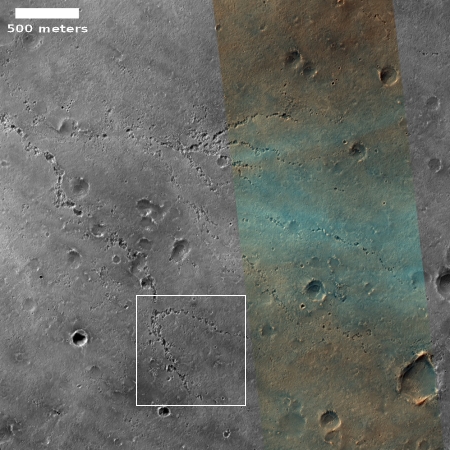

Cool image time! The photo the right, rotated, cropped, and reduced to post here, is not only cool, it contains a punchline. It was taken by the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) on February 11, 2020 and shows one small area between two regions in the northern lowlands of Mars, dubbed Amazonia Planitia (to the south) and Arcadia Planitia (to the north) respectively.

This region is thought to have a lot of water ice just below the surface., so much in fact that Donna Viola of the University of Arizona has said, “I think you could dig anywhere to get your water ice.”

I think this image illustrates this fact nicely. Assuming the numerous depressions seen here were caused by impacts, either primary or secondary, it appears that when they hit the ground the heat of that impact was able to immediately melt a wide circular area. My guess is that an underwater ice table immediately turned to gas so that the dusty material mantling the surface then sagged, creating these wider circular depressions.

Of course, this is merely an off-the-cuff theory, and not to be taken too seriously. Other processes having nothing to do with impacts could explain what we see. For example, vents at the center of these craters might have allowed the underground ice to sublimate away, thus allowing the surface to sag.

So what’s the punchline?

» Read more

Cool image time! The photo the right, rotated, cropped, and reduced to post here, is not only cool, it contains a punchline. It was taken by the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) on February 11, 2020 and shows one small area between two regions in the northern lowlands of Mars, dubbed Amazonia Planitia (to the south) and Arcadia Planitia (to the north) respectively.

This region is thought to have a lot of water ice just below the surface., so much in fact that Donna Viola of the University of Arizona has said, “I think you could dig anywhere to get your water ice.”

I think this image illustrates this fact nicely. Assuming the numerous depressions seen here were caused by impacts, either primary or secondary, it appears that when they hit the ground the heat of that impact was able to immediately melt a wide circular area. My guess is that an underwater ice table immediately turned to gas so that the dusty material mantling the surface then sagged, creating these wider circular depressions.

Of course, this is merely an off-the-cuff theory, and not to be taken too seriously. Other processes having nothing to do with impacts could explain what we see. For example, vents at the center of these craters might have allowed the underground ice to sublimate away, thus allowing the surface to sag.

So what’s the punchline?

» Read more