The strange squashed ridges at the basement of Mars

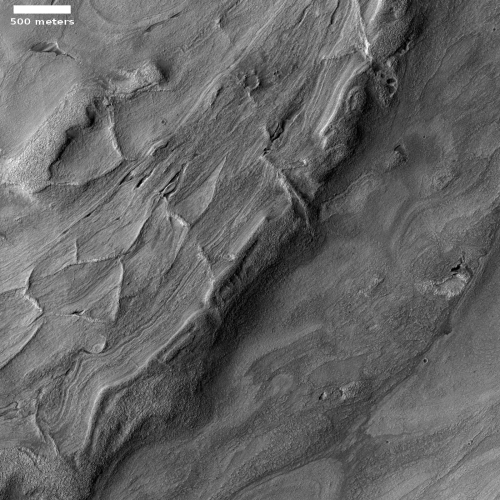

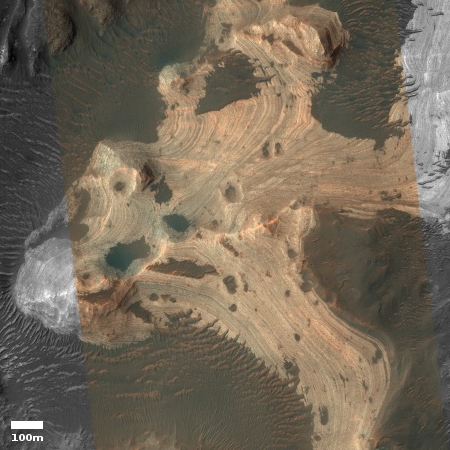

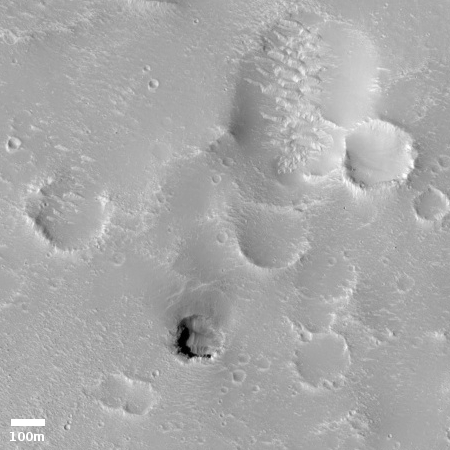

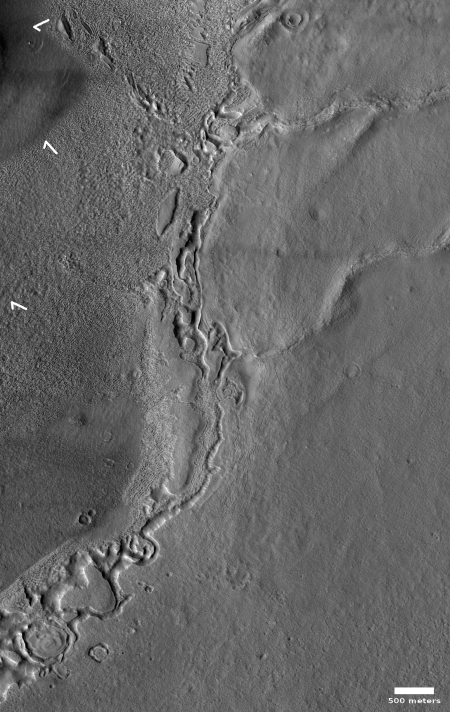

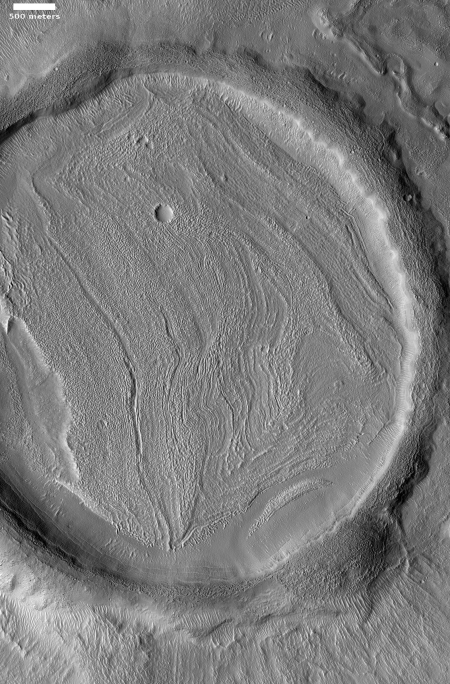

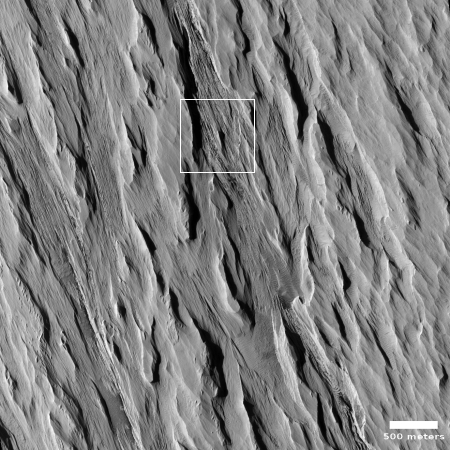

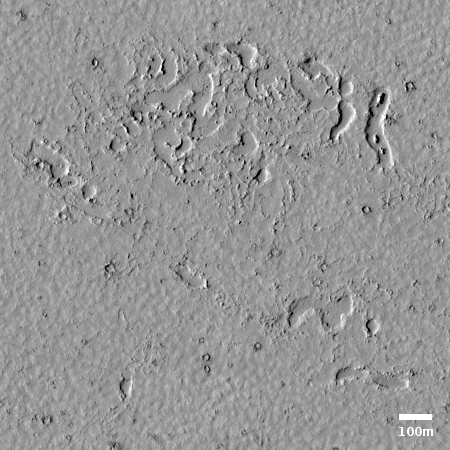

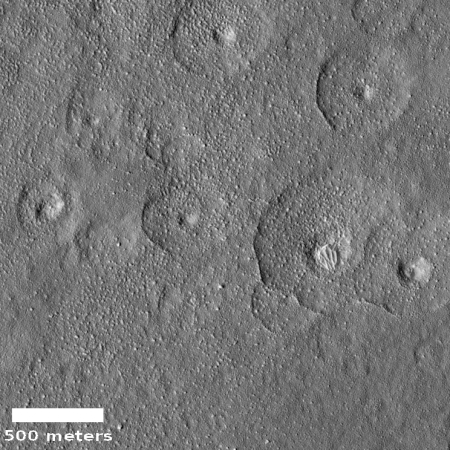

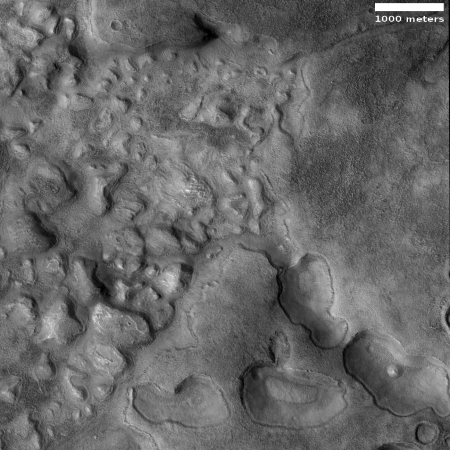

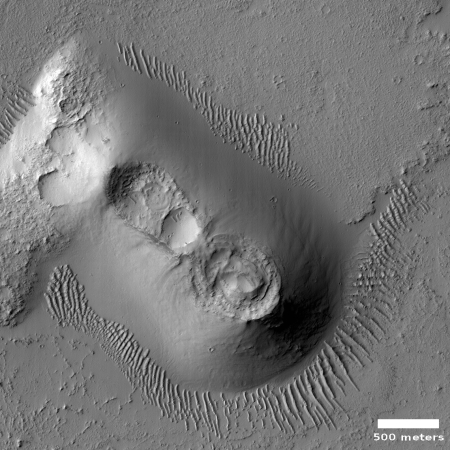

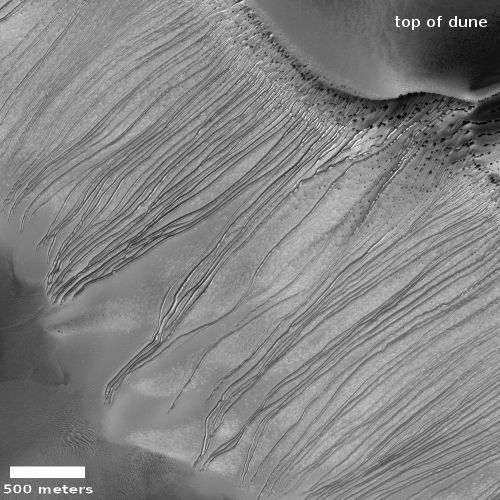

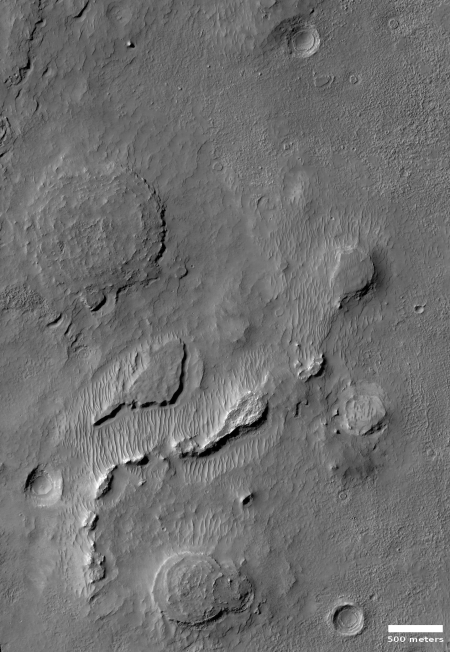

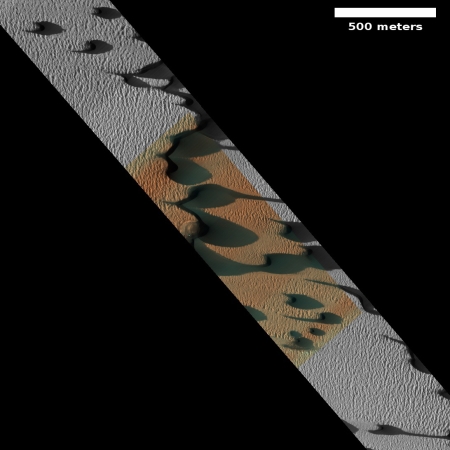

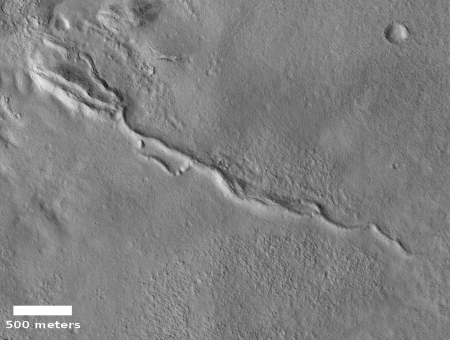

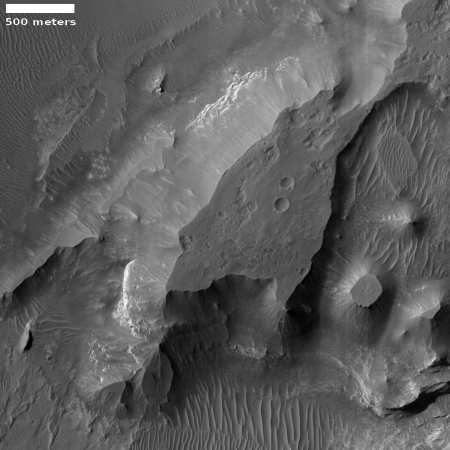

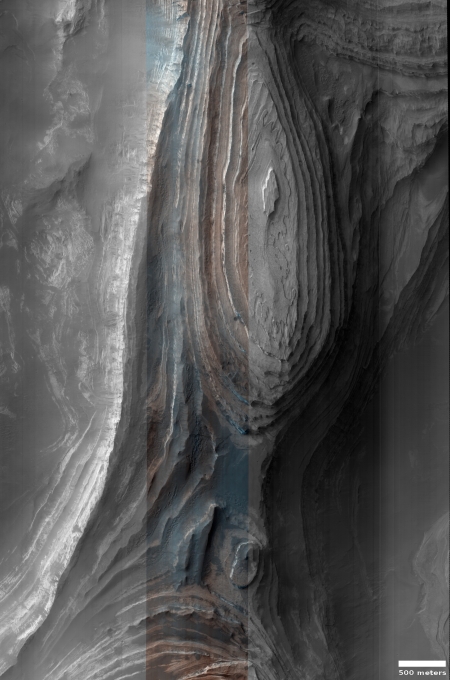

Cool image time! The photo on the right, cropped and reduced to post here, was taken by the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) on April 9, 2020, and shows the very weird and very packed ridges and layers that are found routinely at the deepest part of Hellas Basin, what I have dubbed the basement of Mars.

Be sure to click on the image to see the full photograph. There’s lots more strangeness to see there. And be sure to read my post in the second link, which highlights a similarly strange set of packed ridges, and where I note:

This is the basement of Mars, what could be called its own Death Valley. The difference however is that unlike Death Valley, conditions here could be more amendable to life, as the lower elevation means the atmosphere is thicker.

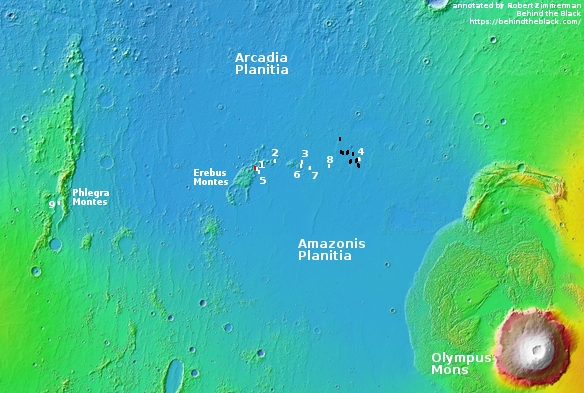

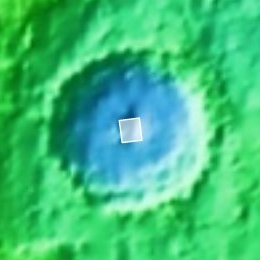

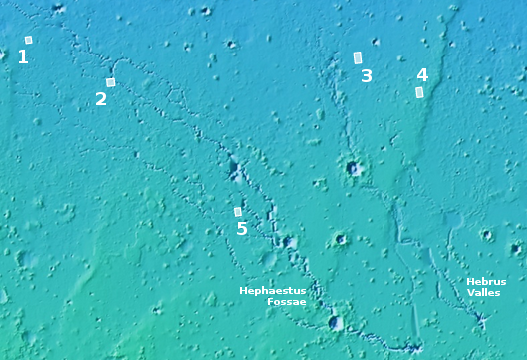

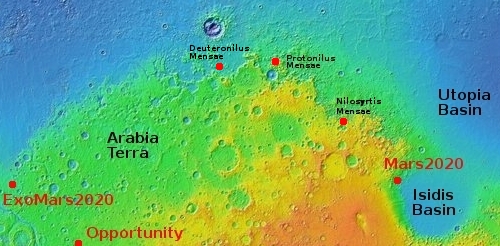

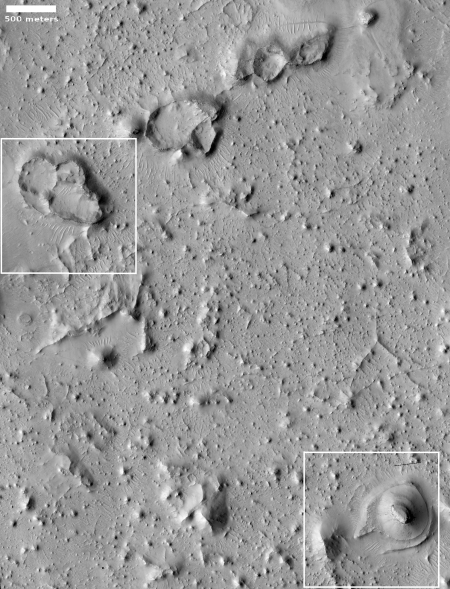

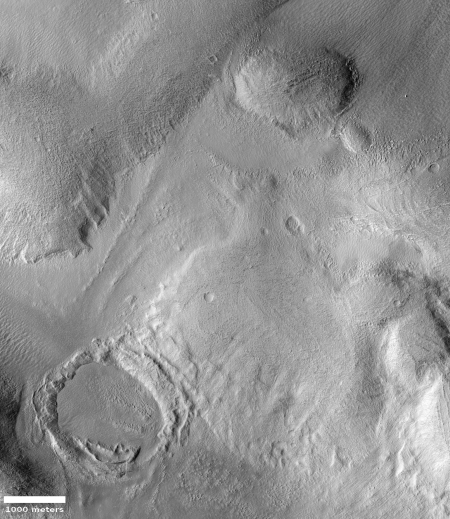

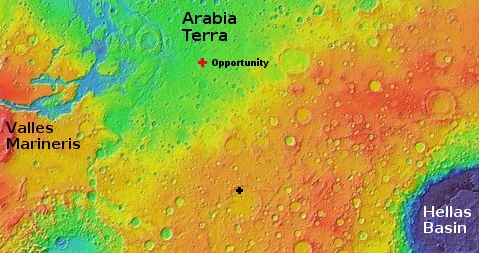

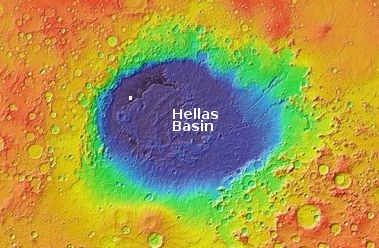

The context map to the right shows Hellas, with the location of today’s image indicated by the white box, close to basin’s lowest point, more than five miles below the basin’s rim. Overall the Hellas Basin is about the size of the western United States, from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean. It is believed that the entire basin was created by a single gigantic impact that occurred about four billion years ago when the solar system’s inner planets were undergoing what has been labeled the Late Heavy Bombardment.

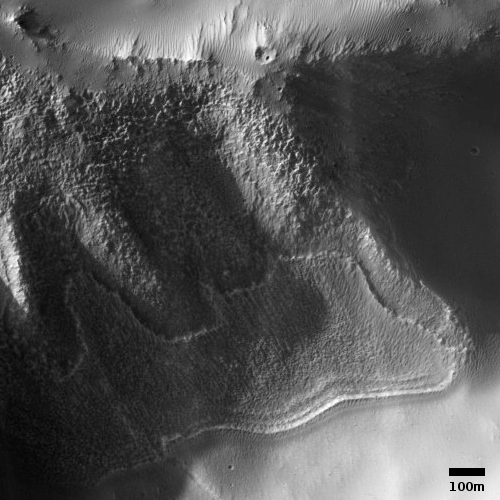

The specific process that formed these ridges, dubbed honeycomb terrain by scientists, remains unknown however. There are of course theories, none of which are very convincing. Here’s mine, as outlined in the previous post:

» Read more

Cool image time! The photo on the right, cropped and reduced to post here, was taken by the high resolution camera on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) on April 9, 2020, and shows the very weird and very packed ridges and layers that are found routinely at the deepest part of Hellas Basin, what I have dubbed the basement of Mars.

Be sure to click on the image to see the full photograph. There’s lots more strangeness to see there. And be sure to read my post in the second link, which highlights a similarly strange set of packed ridges, and where I note:

This is the basement of Mars, what could be called its own Death Valley. The difference however is that unlike Death Valley, conditions here could be more amendable to life, as the lower elevation means the atmosphere is thicker.

The context map to the right shows Hellas, with the location of today’s image indicated by the white box, close to basin’s lowest point, more than five miles below the basin’s rim. Overall the Hellas Basin is about the size of the western United States, from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean. It is believed that the entire basin was created by a single gigantic impact that occurred about four billion years ago when the solar system’s inner planets were undergoing what has been labeled the Late Heavy Bombardment.

The specific process that formed these ridges, dubbed honeycomb terrain by scientists, remains unknown however. There are of course theories, none of which are very convincing. Here’s mine, as outlined in the previous post:

» Read more